Canada’s New Democratic Party (NDP) proposed a new wealth tax plan in parliament Nov. 16. The plan was to implement a one per cent tax on peoples’ wealth that exceeds $20 million. The NDP also advocated for a plan to tax capital gains at a higher rate, which now sits at 50 per cent.

Unfortunately, the Liberal Party of Canada (LPC), Conservative Party of Canada (CPC) and the Bloc Québécois (BQ) formed a united front to block the motion in parliament despite the fact that an overwhelming majority of Canadians support the NDP’s proposal.

According to a poll done by Broadbent Institute, a Canadian think tank, roughly 91 per cent of NDP voters, 70 per cent of CPC voters, 87 per cent of LPC voters and 66 per cent of BQ voters are in favour of taxing the rich to pay for Canada’s economic recovery. Yet, only the NDP and Green Party of Canada voted in favour of the motion.

This should be considered a tragedy to Canada’s so-called representative democracy — very rarely are policies so universally favoured in such a bipartisan way. And historically, high taxes on the wealthy was not abnormal. However, there is an explanation as to why these political parties chose to align themselves with the wealthy instead of the democratic consensus of Canadians.

In post-Second World War society, the rich were used to paying higher tax rates than other socioeconomic statuses. As a matter of fact, by 1948, individuals making more than $250,000 annually — $2.37 million in today’s standards — were taxed roughly 80 per cent on their incomes. Now, the highest tax bracket is roughly 33 per cent for individuals making over approximately $215,000 — this includes all taxable incomes from $215,000 and up.

Accompanied by extremely high involvement of the government in public spending, employment and taxation on the wealthy, this period witnessed unprecedented growth without an economic crisis for nearly 30 years — a massive feat for an economic system that had a reputation of collapsing after coming out of the Great Depression. This type of economics, formally called the Keynesian economic consensus, managed to dig a world decimated by decades of gruesome crises into a period that experts often refer to as the “Golden Age of Capitalism.”

Economists and government technocrats thought they figured out the perfect balance between government and capitalist enterprise — Keynesianism was the best thing since sliced bread. Their strategy was to spend before they saved, rely on high inflation with high growth and increase wages to the liking. The private sector was following the lead of a dynamic public sector and their high wages. More of the pie was being divided for the working classes, and the ultra-rich were paying for it.

But, in recent decades, there has been a markedly noticeable tendency of government bodies to advocate for cutting, privatizing and deregulating the public sector, instead of spending, investing and expanding the role of government. So, what happened? Many historians have argued that the rapid change of global governments’ attitudes in spending was directly correlated to a political coup that the rich subtly made on the very institutions that kept their profits in check. Notably, the mechanisms that kept the international liquidity of the rich’s capital flow restrained.

The mechanisms enforced by the international Bretton Woods financial systems required investors to go through a lengthy application process in order to pull their money out of any given national economy. But, through political lobbying, gradual reform and watered-down legislation, these mechanisms were deteriorated in North America and, later, globally.

Now, investors are able to move their money around, pretty well and as they please. This means that governments’ interests are not simply aligned with its citizens — instead, governments must compete for capital investment with other nations.

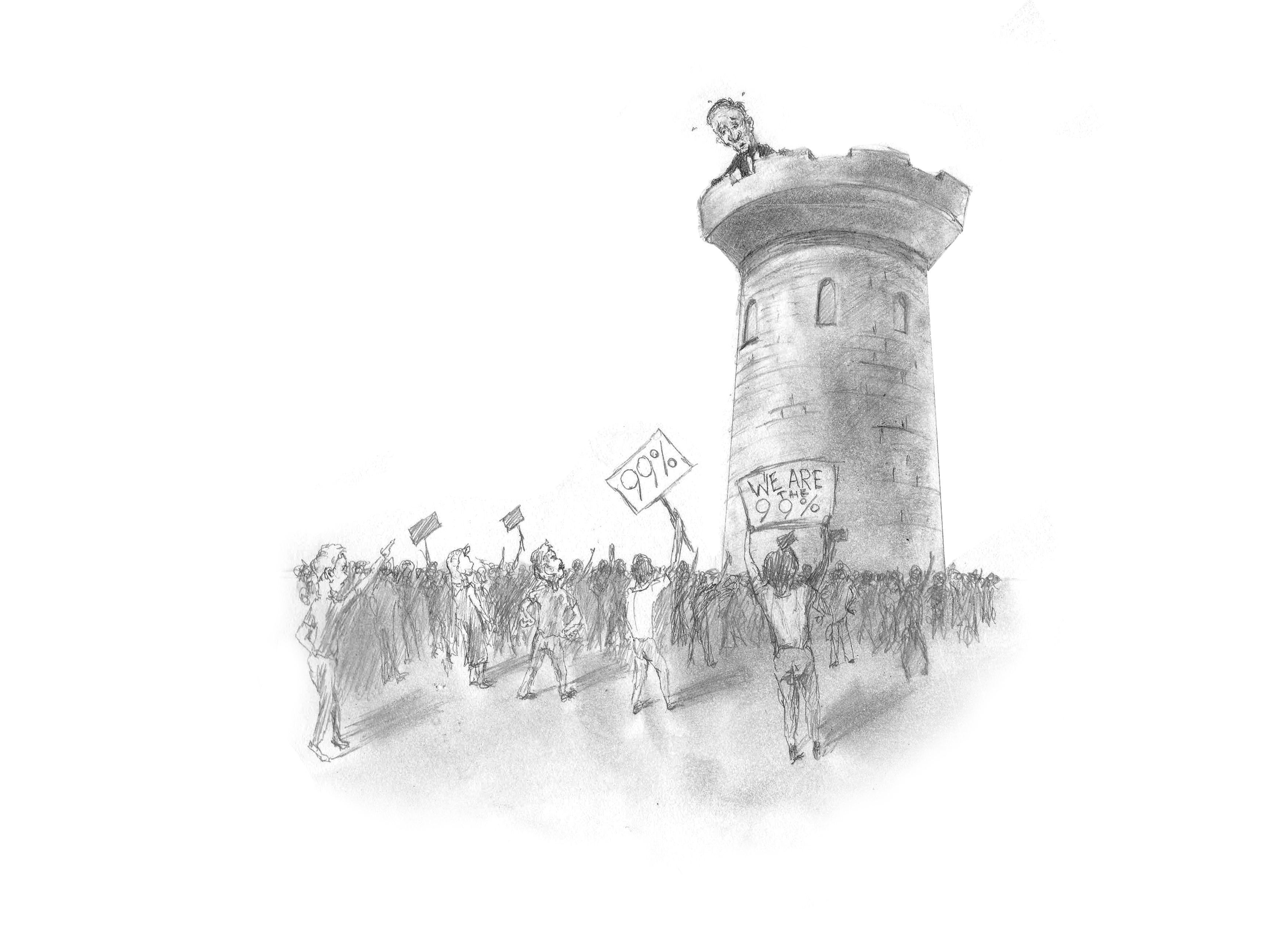

If governments adopt unwanted legislation that reduces the profits of an investor, those investors could simply pull their money and leave the economy in disarray. In a way, large corporations and the very rich act as a “virtual senate” that can strike down legislation in unrelenting fashions. This is largely why many governments choose to adopt policy to attract private direct investment as opposed to taxing and redistributing wealth through public infrastructures.

But, like the post-war world, Canadians are going to need a progressive tax plan again. The COVID-19 pandemic has impoverished thousands, and thousands more are likely toeing the poverty line. Simultaneously, however, the wealthy seem to be making more than ever.

The government has gone billions of dollars into deficit. The Parliamentary Budget Officer, a public financial advisory office, predicted in April that the deficit left from 2020-21 will be roughly $252 billion. Currently, the deficit is sitting at approximately $343 billion — over $100 billion more than one of the government’s key financial institutions predicted. And, given the unpredictability of the COVID-19 pandemic, expect the deficit to grow further.

The current debt situation is striking seeing as the Canadian government ran a $25 billion deficit in 2019-20. If Canada’s parliament rejects a tax plan to raise taxes on the wealthy, the majority of Canadians will likely pay for the crisis in the form of austerity — a move that could impoverish more Canadians.

Expecting everyday people — who are struggling to get by during this unprecedented crisis — to pay for the economic devastation of COVID-19 will not do.

Wealthy individuals making inordinate gains while the majority of Canadians continue to make sacrifices for the namesake of public health is deplorable. Make the rich pay their fair share. Make the rich sacrifice, just as the rest of us have. It has been done before, and it is not a radical idea.