In recent weeks, practically the entire world has been shaken by the COVID-19 pandemic.

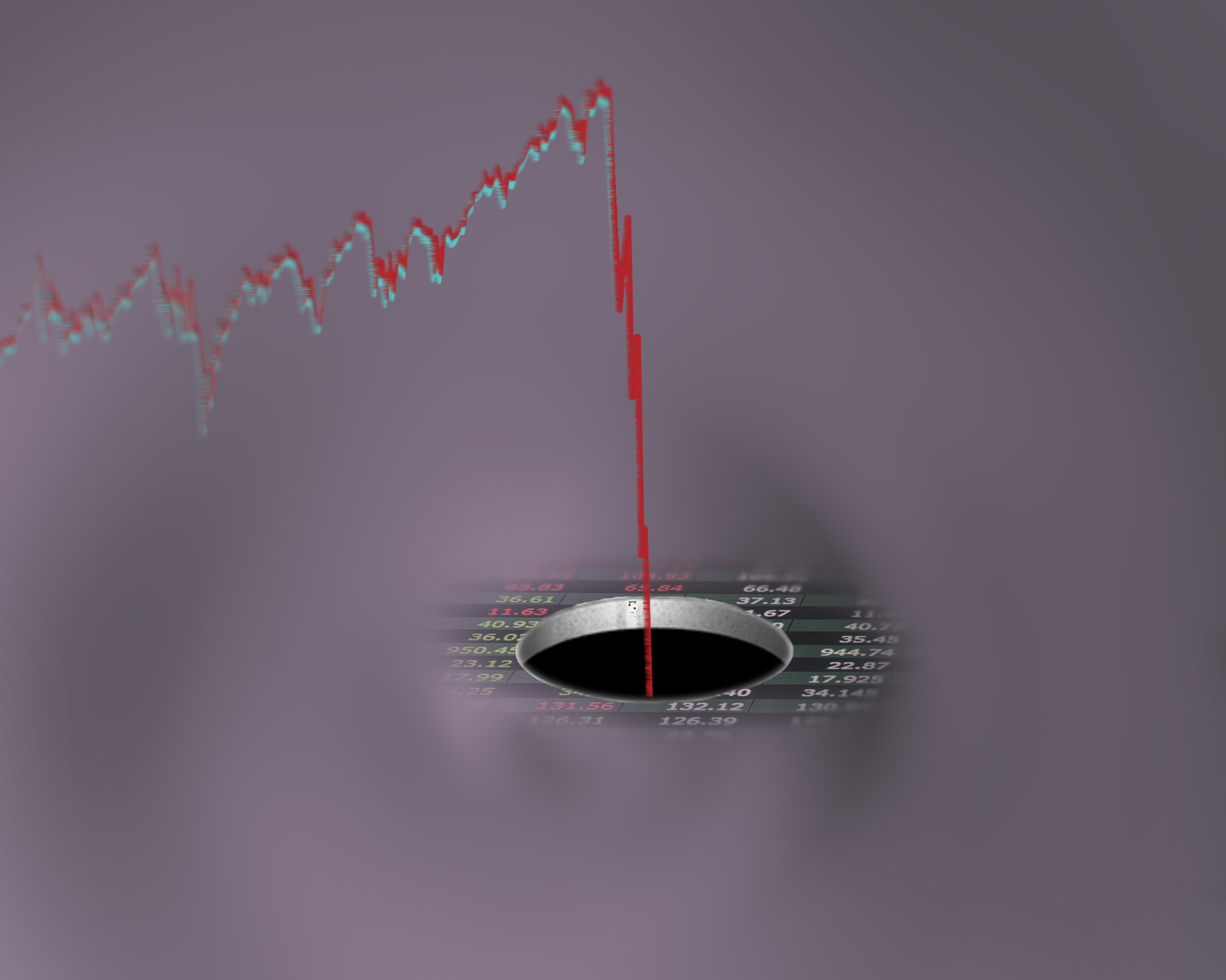

The stock markets have been plummeting, thousands have been laid off from their jobs and a state of emergency has been declared in Manitoba.

The government response to the crisis has been unsurprising to say the least. Nonetheless, from a political and economic standpoint, it is intriguing. We are experiencing history.

Billions of dollars in stimulus are set to be given to suffering industries such as airlines and the oil and gas sector. The Bank of Canada is dropping interest rates to less than one per cent. Mortgage payments are being deferred and wages are being subsidized.

All of these measures are excellent news to anybody lucky enough to own businesses or properties.

For the vast majority of people, the direct financial support is being given through tax credits such as the GST top-up payment, which promises roughly $400 payable to single adults who filed taxes. But in Manitoba, this does not even cover a rent payment for many people.

Another way direct financial support is being given to Manitobans is in the form of enhanced employment insurance (EI) benefits, which can give up to $900 bi-weekly for up to 15 weeks to those workers who are unable to work due to the pandemic and do not qualify for EI.

Massive amounts of financial aid are about to be sent directly to sectors like airlines — which failed to keep cash reserves and instead opted for stock buybacks — and the oil and gas sector, which for years has been in decline and needs to be phased out.

Mortgage payments can be deferred, yet renters are expected to continue paying rent.

Business owners are further being helped with their bottom line through wage subsidies and increased credit availability.

Only people who are up-to-date on their taxes will receive the GST top up — not to mention that this support will not be available until May.

Overwhelmingly, these measures benefit those with the most wealth — people who own businesses and properties and are therefore able to extract profits or rents from the labour of others.

Economic logic dictates that in a crisis such as this, the most effective way to prevent a downward spiral which leads to another economic depression is to dramatically increase government spending and get money into the hands of the majority of people — who will more than likely immediately spend it on necessities — keeping the economy running.

Keeping in line with this logic, across the political spectrum there have been widespread calls for the introduction of a policy called universal basic income (UBI).

The premise of UBI is simple: since the boom and bust cycle inherent to capitalism tends to be caused by a lack of effective demand from average people not having enough money to buy products, giving people money to spend — regardless of their employment status — would ensure effective demand is maintained at a minimum level.

However, there is a risk associated with such measures.

Without the elimination of rents, or at least tight control of them, UBI could potentially serve as nothing but a subsidy for landlords, enhancing their ability to accumulate wealth while renters remain in exactly the same position.

If such a thing were to happen, the macro-economic benefits of UBI would essentially be lost — inequality would likely only continue to grow as property becomes evermore concentrated in the hands of a few people.

Of course, it is no surprise that the emergency measures already announced overwhelmingly support business and property owners — after all, we do live in a capitalist society where the state serves only the bourgeoisie — or at the very least maintain an acceptable enough institutional environment for profit to occur at a reasonable enough rate.

Income taxes were introduced as a temporary emergency measure and remained beyond the initial crisis that birthed them — the same could happen with UBI.

The emergency care benefit, an enhanced form of employment insurance, is close enough that it could serve the same purpose.

Throughout the history of capitalism, crises have almost always led to a massive change in political economy. Think about the rise of Keynesianism after the two world wars, and the rise of neoliberalism after the economic crises of the 1970s.

We are experiencing history. Where we go as a society is in flux, and now is not the time to be quiet.