The world’s rarest marine mammal, the vaquita porpoise, has lost half of its population in one year.

Just last year, it was reported by the Committee for the Recovery of the Vaquita (CIRVA) that there were approximately 60 vaquitas left in the wild. Currently, CIRVA has estimated there to be just 30 vaquita porpoisesst left in the wild.

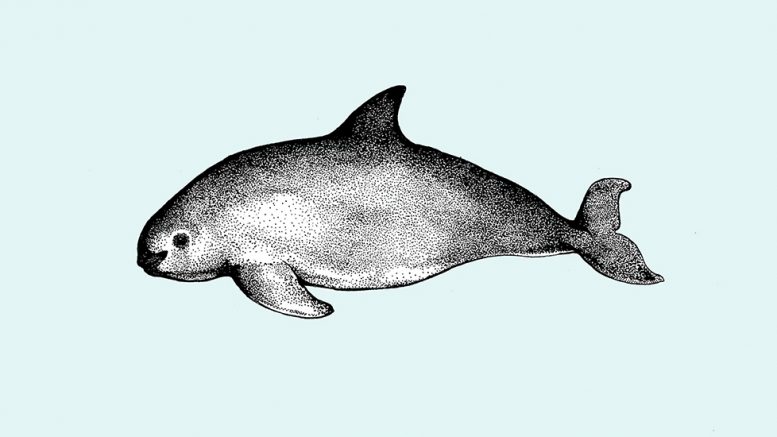

It was not always this dire for the vaquita porpoise. Sadly, their population has declined by 92 percent in just 20 years. The vaquita porpoise is the world’s smallest cetacean (typically they reach about five feet in length and weigh around 120 pounds) and only exists in Mexico’s northern Gulf of California.

The World Wildlife Federation (WWF) and the Mexican government are at odds over how to approach this critical situation. While the WWF is calling for an outright fishing ban in the Gulf of California, Mexican authorities, believing this to be too costly, have suggested instead placing several of the remaining vaquitas in custody, in hopes of preserving the species.

However, choosing to take the capture route in the case of the vaquita porpoise is dangerous and considered a last resort. With only 30 vaquita porpoises left, losing even a handful of vaquitas in the capturing process could permanently render the species extinct.

Mexcio has already banned illegal gillnet fishing near the vaquita porpoise’s habitat. The government has offered $74 million to locals over two years in hopes that the compensation would supplement what locals who rely on gillnet fishing would lose from the ban. Despite this, many fishers are ignoring the ban, and are continuing to gillnet fish while eluding authorities.

“This breaks my heart,” said Leigh Henry, WWF senior policy advisor. “Wildlife conservation can be a tough job. What’s so devastating about the vaquita is that it could go extinct with the majority of the world having no idea this beautiful animal even existed.”

“But I refuse to give up hope. We’ll fight on.”

Vaquita porpoises have died at such a rapid rate mainly because of something called “bycatch,” which occurs when a marine species lives too close to a more sought-after marine species, and is caught in illegal gillnets set out by fishers who mean to catch the other species. In the vaquitas’ case, they habituate the same area as the totoaba fish. The totoaba, which is also endangered, is pursued by fishers for its swim bladder, which is used in a Chinese medicinal soup believed to improve fertility. The WWF is also calling for the US and China to end the shipment and sales of totoaba-based products.