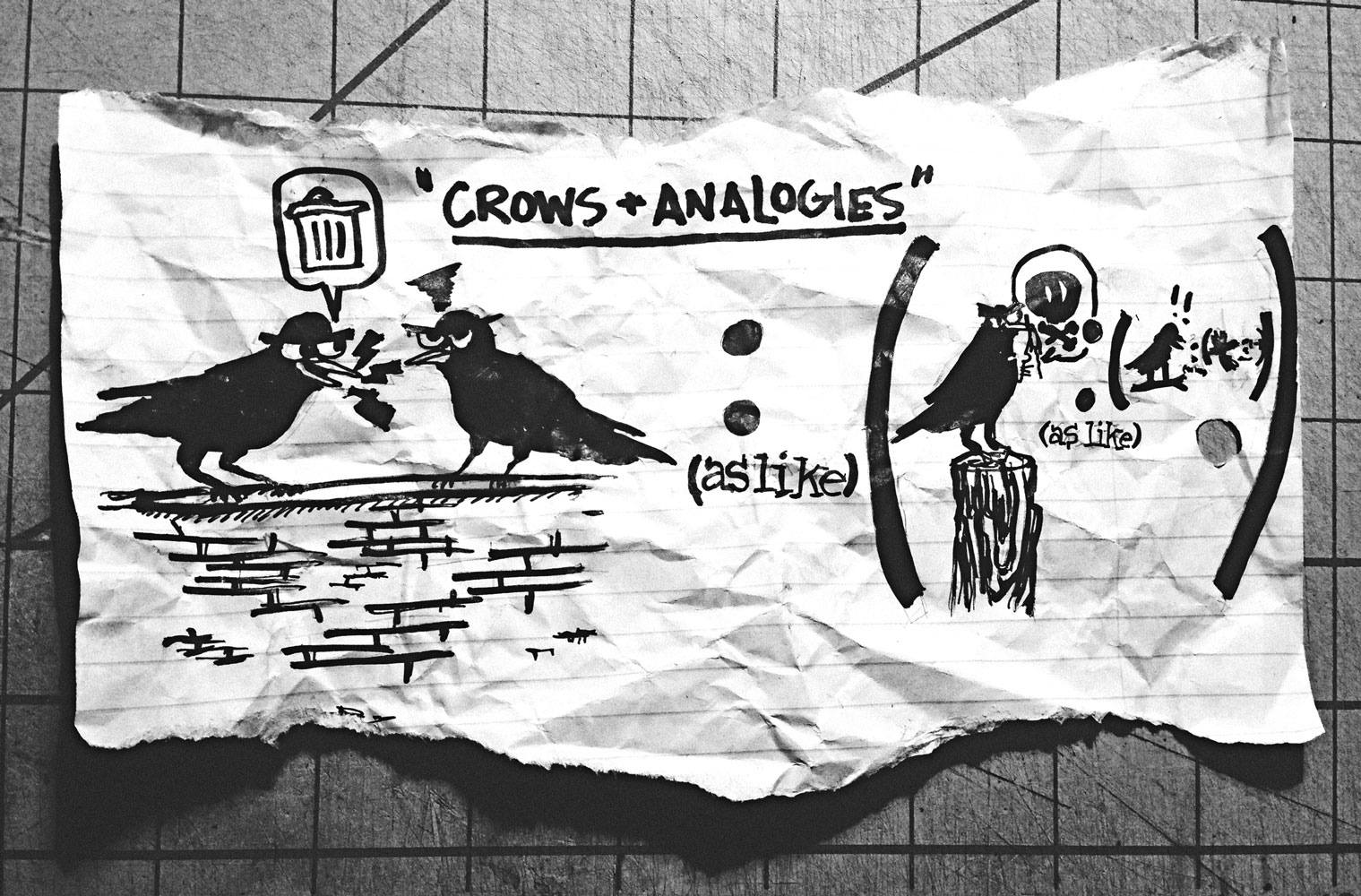

Crows are extremely intelligent birds that are part of the corvid family, which also includes magpies and blue jays. Research done in collaboration between Moscow State University and the University of Iowa shows that crows are capable of analogical reasoning. This same reasoning does not develop in humans until the age of three or four.

The study relies on the crows’ ability to identify “sameness,” the characteristics between two objects that makes them the same. The crows were presented with three cards with a pair of shapes on each of them that differed in type, colour, and size.

The crows were tasked with choosing the flanking card that was analogous to the middle card. This ability, termed relational matching-to-sample, can be demonstrated using letters.

Which is analogous to BB? CD or EE. Okay. Which of those is analogous to AB? These were the kinds of problems that the crows were presented with. They succeeded over three-quarters of the time and did so spontaneously, without prior training.

Debbie Kelly’s research at the University of Manitoba

Interest into the social brain hypothesis helped focus research interest onto corvid intelligence.

According to psychology professor Debbie Kelly, the social brain hypothesis states that “[if] a species has long developmental periods, lives to a long age, lives in a complex social group, and has the right hardware, those are the prime things for the evolution of intelligence [ . . . ] A lot of the corvids fit into those categories.”

“Research just started pouring out showing that birds can plan, they can reason for the future, they can do relative concept learning,” said Kelly. “And that just snowballed.

“We’re studying the Clark’s nutcracker. It’s not a social bird,” said Kelly. “It’s a food-storing bird and it stores 10 to 30 thousand seeds in the mountains, and then six months later it has to go and remember where those seeds are.”

“What seems to be the key is that they learn it relationally,” said Kelly. They remember where their caches are by learning its position relative to landmarks, such as between two trees.

“We have just submitted a paper that is very similar to the analogy paper. We have shown for the very first time a corvid that is better than any non-human primate studied to date in being able to quickly form a relative concept,” said Kelly.

Clark’s nutcrackers that were presented with samples of eight images can determine same versus different, even with images that they have never seen before.

“Rhesus monkeys needed more training than that,” said Kelly. “None of the other species tested were able to do it with as few examples as the Clark’s nutcrackers.”

I’ve just seen a face

Research published in 2012 from John Marzluff’s lab at the University of Washington shows how well crows remember human faces.

Crows use both dangerous firsthand experience and word-of-beak social information to distinguish the faces of dangerous humans. The tradeoff for the crows is accuracy versus cost.

Crows typically respond to dangerous individuals by scolding them, characterized by aggressive crowing at the individual, typically following them around in a big mob.

In the study, researchers wore a unique “dangerous face” mask while capturing, banding, and releasing crows. The captured crows immediately scolded the dangerous face.

The number of scolding crows increased over a number of years, and the scolding area steadily grew.

Bystander crows witnessing the masked individuals capturing their friends would join in on the scolding of the dangerous mask.

Unaffected crows learned to scold the dangerous mask by joining in mobs with previously captured crows, a form of horizontal social learning.

Younger birds that were born after the capturing took place were taught by their parents to scold the dangerous mask, a form of vertical social learning.

Cause and effect

In 2012, Bryce Hoye wrote for the Manitoban about new research at the time indicating that crows are capable of causal reasoning, the ability to understand cause and effect.

Another study from early in 2014 showed that a crow’s level of casual intelligence rivals that of a five-year-old.

Aesop’s fable The Crow and the Pitcher tells the story of a thirsty crow that comes upon a pitcher containing water that it can’t reach. Too weak to push the pitcher over, the crow drops pebbles into the pitcher one after the other until the water level rises enough for the crow to drink.

The 2014 study presented crows with Aesop’s fable. Crows presented the ability to raise the water level in glass tubes by dropping objects into them, understanding to choose solid objects over hollow ones and sinking objects over floating ones.

Why birds, why now?

Crows and other animals are burdened with the task of adapting to human-made urban environments.

“Cognitive abilities help us to get into all sorts of different environments. That probably is what selected for this behaviour in crows too,” said U of M biological sciences assistant professor Kevin Fraser.

“There is a climate change context here too. Birds that are most flexible and able to figure out new problems are more likely to be the ones that can deal with the changing environment,” said Fraser.

The list of fascinating studies on crow behavioural intelligence goes on and on. They are remarkably intelligent birds.