An international research team, including U of M professor Dorthe Dahl-Jensen, has achieved a remarkable milestone in a remote location in Antarctica. The team successfully drilled a 2,800-metre-long ice core, reaching the bedrock beneath the Antarctic ice sheet. This accomplishment has resulted in the retrieval of the oldest ice core ever, providing valuable insight into earth’s climate history spanning the past 1.2 million years.

Dorthe Dahl-Jensen is a Canada excellence research chair and professor in the U of M’s Clayton H. Riddell faculty of environment, earth and resources.

“I’ve always been very fascinated by snow and ice,” she said. “I love being outside in the wilderness. And I started doing that when I was a high school kid through scout activities, and when I learned you could work with it as your profession, you know working with ice and climate, I decided that would be the way I wanted to go.”

Dahl-Jensen pursued her education at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, where she became a professor in 2001.

Her research career has been centred on ice core drilling, beginning with the Greenland ice sheet during her tenure in Copenhagen. Later, she joined the European Commission-funded Beyond EPICA (European Project for Ice Coring in Antarctica)-Oldest Ice project, which focuses on drilling ancient ice cores in Antarctica using advanced drilling technology.

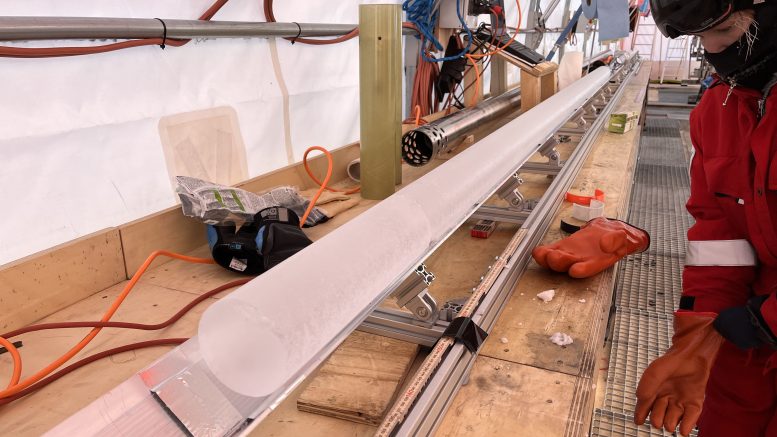

“It’s been super fascinating to be able to drill these ice cores,” Dahl-Jensen said. “Where you kind of start at the top, and then as you go down, you get through layers of ice that’s older and older until you reach the bedrock, normally two to three kilometres down, and there the ice is very old. In Greenland, [the ice is] 150,000 years old, and now in Antarctica 1.5 million years old.”

She explained that researchers can gain valuable insights from the long-term climate records into how the climate has behaved over time.

Modern weather stations have provided data for the past 150 years. These ice core records reveal a broader history of warmer and colder periods, along with significant natural atmospheric changes that have occurred independently of human activity.

Understanding the record of history, she emphasized, is crucial for learning about the climate.

Research indicates that ice cores dating back 1.2 million years reveal a period when greenhouse gas levels and temperatures were significantly high. These findings offer valuable insight into what our future climate may look like in a warmer world with increased greenhouse gas.

Currently, Dahl-Jensen’s team is continuing their work on the Beyond EPICA-Oldest Ice project in Antarctica while also preparing to begin a new ice core drilling initiative in Nunavut.

“This spring, we will drill an ice core up in Nunavut, in Canada,” she said. “It’s closest to Grise Fiord along the Baffin Bay, but it’s up on Axel Heiberg Island and the ice cap is called the Müller ice cap. And here we will drill 600 metres and learn about the history of the sea ice in the Arctic Ocean.”

The Nunavut project will involve collaboration among several universities across Canada, with her vision of working together with a diverse group of researchers. She also hopes to include community members from Grise Fiord in the initiative.

“I’m trying to bring my expertise in drilling ice cores to Canada and form more Canadian projects, which I think is really great,” she said. Dahl-Jensen emphasized that this project offers students a unique opportunity to participate in impactful research and build networks across Canada.

She is currently seeking graduate students to join the Müller ice cap project and encouraged interested individuals to reach out via email to collaborate on upcoming initiatives.

“[Manitoba] reaches right up to the Hudson Bay where Churchill is,” she said. “In that way, we are also a very Arctic university and do a lot of research up there.”

Dahl-Jensen discussed the importance of Arctic research, emphasizing current conversations about the impact of diminishing sea ice on polar bears and the broader consequences for Canada’s lake systems, especially in Manitoba.

“I really enjoy being at the University of Manitoba and also being in Canada,” Dahl-Jensen said. “My background is in Denmark, but I feel it’s really nice to come to Canada.”

“I love the work, which brings me more in contact with communities in the Baffin Bay area.”