Imagine a future where robots are not only tools but also serve as companions in our daily lives, providing emotional support and enhancing well-being.

James Young is a professor in the U of M’s department of computer science.

Young studied computer science, which involves learning algorithms for programming computers.

“Honestly, it kind of just happened,” he said. “I just worked hard at school and took opportunities that came up.”

At the beginning of his research career, Young realized that people often wasted a lot of time arguing with computers to perform what they wanted.

He was interested in how humans could program computers to be more user-friendly and began researching new ways to interact with and use computers.

“Robots provide very different ways that we might interact with them, instead of a keyboard or a mouse,” he said. “We can use a smile or talk or point and use our bodies in different ways. So, I got my hands on some robots very early in graduate school and have done a lot of work with programming them.”

Young’s recent research is in domestic robots, or robots for homes.

“There’s a lot of research now that shows how these social robots, they can help you feel better, they can reduce anxiety,” he said. “They can be kind of like a fake companion, kind of like a pet, but not quite.”

However, Young explained that there are no social robots in people’s homes yet; every time a startup firm is formed, it fails or does not become a product.

“I’m very interested right now in what’s stopping these [social] robots from becoming regular use,” he said. “I have PhD students and mastersstudents who are making robots and programming robots, and we’re putting them in homes.” Young added that his

PhD student, Danika Passler Bates, is interviewing robot owners to explore when individuals lose interest in their robots, the reasons behind discontinuing use and how to promote continued usage.

Young’s current research focus is on how to create these robots for sustained usage in people’s homes, so that they may realize the benefits that we learned from research.

“I think it’s very interesting to think about not only what we can do with cutting edge technology, but what can we do [that’s] new with existing technology,” he said. “I really try to take a step back and use existing technology more cleverly.”

“I see myself kind of as a designer that way where we want to redesign interaction or redesign these devices so that we can save money, make them more robust. For example, my student, Danika, her masters project, she made a robot called SnuggleBot.”

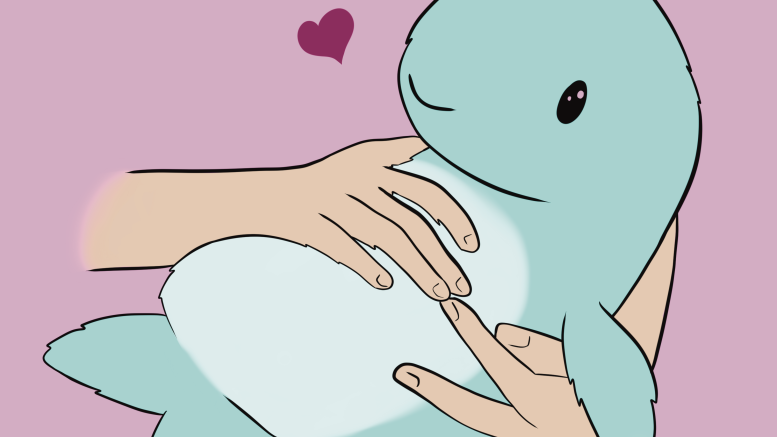

SnuggleBot is a “very cute” narwhal robot which can be cuddled and squished.

A competitor robot named Peril is also in the marketplace. Peril is a steel robot, and it can recognize people’s faces.

“[Peril] can remember details about you and can do scheduling, and it costs $10,000,” Young said. “A SnuggleBot we made for less than $200 in-house, and it’s very robust.”

“But instead of having [Peril’s] computer-driven experiences like it’s remembering your face, it’s giving you a schedule, the data designed it to make the person have to take care of it.”

He elaborated, the robot must be kept warm to avoid colour changes or freezing. To do this, one must remove the pouch and microwave it. This strategy encourages the user to take responsibility for the robot, making it a natural part of their daily routine.

“We know from psychology research that caring for a pet, caring for another person, caring for plants even can help you feel better,” he explained. “So, we’re trying to encourage interactions that help you feel better and bond with the robot without requiring all this expensive or high technology.”

Social robots may need hugs. They can get lonely and turn purple. When you go up and hug it, it may make you feel better as well.

“I think there’s a lot of potential for social robots to add just a little bit of improvement to our everyday lives,” Young said. “We’re just trying to find ways that actually work for people in their everyday lives.”