Picture this: you’re scrambling into a public washroom, clutching your abdomen at the eleventh hour. You pick the perfect unoccupied stall — no neighbours — and throw your pants down to hurl yourself onto that unnervingly damp plastic seat.

Before you can finally release your cargo into the outside world you hear a cough. Your rectum seizes up as your body is petrified by shame and self-consciousness. If you resume, someone in this bathroom will know you’re pooping.

The thought alone is enough to make one flush with embarrassment.

Even though most people simply go to the bathroom to pop a squat, the prospect of proximity to other people in the pooper can inspire surprisingly complex emotions. Toilets are among the foremost political and ideological battlegrounds in the world, and we are remiss not to think more carefully about them.

Take Amoowigamig, a public washroom that opened on Main Street in Winnipeg, to service Winnipeggers downtown. The bathroom saw its hours cut in May this year because — surprise — people were using it. Amoowigamig’s operating costs surpassed its $200,000 budget.

The decision to cut back Amoowigamig’s hours rather than expand them was, to be blunt, a load of dookie. The bathroom serviced both unhoused Winnipeggers and random passersby who needed to do their business. It seems to me that publicly available washrooms ensure that less people have to pee on the street.

Winnipeg’s bylaws do not mandate that businesses with bathrooms allow members of the public to do their business in those bathrooms. Food and dining services must have a bathroom for patrons, but therein lies the problem. Some people can’t pay, but everybody poops.

Yes, everybody poops, and yet there are so many rules about when and where we’re allowed to do it. We frown upon and even outright forbid people hurrying off to the water closet, as if it’s better for them to pee or poop in their seats. During one of tennis player Coco Gauff’s matches at the recent US Open, the umpire told a man in the audience to sit down when he tried to go to the washroom.

I peed before boarding a flight back from Toronto this summer, but my bladder was somehow full to bursting 40 minutes later as we were starting to take off. Despite sitting right next to the toilet and the plane being airborne, I couldn’t bring myself to go until the seatbelt sign was off. There was something about the idea of everyone on the plane knowing what I was up to that made me think holding it was better than just opening the flood gates.

Bathroom rules are not universal. Toilets around the world expect different things from those who use them with varying levels of guidance.

North American bathrooms are devoid of essentials like bidets and floor-to-ceiling stall walls in favour of maniacally wide gaps, so occupants can make eye contact with passersby while cinching off another nugget. Toilets in many parts of Europe feature a person who demands payment before entry. In Greece, users have to toss poopy paper in a reeking bin rather than flush it. Countries around the world use squat toilets that look like misplaced urinals.

I’ve only ever encountered one person who thought about this wide variation in-depth.

Slime-coated outrage merchant and philosopher Slavoj Žižek once spoke about toilets as metaphors for ideology. In his words, “you get on the toilet, and you sit on ideology.” Our precious porcelain thrones sample societal attitudes, like disgust, suggesting something about where that attitude comes from and how we deal with it. This is how he accounts for all the toilet variants we find around the world.

In my opinion, washrooms say something about power. That is, we are only okay if others are privy to us squeezing deuces in the lavatory if we see them as equal counterparts outside.

The segregation of bathrooms has so often been a wedge representing wider bids for domination. It really doesn’t matter where someone goes to the bathroom so long as it doesn’t pose a risk to public health, like pooping in the street. Everyone wins if everybody can poop in toilets.

Under Jim Crow in the United States, Black folks were not allowed to use designated white washrooms. In some ways, segregated washrooms were both part of the enforcement of white supremacist ideology on the population as well as representations of the whole system. White America’s fears about Black folks reaching parity in white society played out with the bathroom.

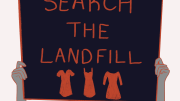

There is a similar anxiety in anti-trans bathroom bills. Cis society’s fears about standing shoulder to shoulder with trans people in public, about trans people existing, play out in these bathroom bills.

What better way to ensure total domination over a group of people than to restrict where they do their business?

Restricting some people’s access to certain bathrooms is almost never paired with making sure a bathroom, any bathroom, is available to them as an alternative.

We all have to think about going to the bathroom daily, yet accessing the washroom is never a simple matter, even for those of us who overcome internal blockages about using public ones. This is the potty problematic — little is ever done on a grand scale to protect bathrooms from perpetually becoming mini-arenas housing political or ideological battles, and the need for bathrooms only becomes more urgent.

Socially, talking about what goes on in the bathroom still carries stigma, and I think one’s reticence to break that wall down plugs up very important conversations that absolutely need to happen. Access to bathrooms should be an irrevocable right for all.

Winnipeggers desperate for a toilet can locate the nearest publicly available bathroom at https://www.winnipee.com/.