In a room on the third floor of Dafoe library, right beside the Icelandic reading room, a small group of archivists work to preserve history.

Since its establishment in 1877, life at the University of Manitoba has reflected the lives of students and faculty from across the province. Those lives and their histories have been preserved by the U of M Archives & Special Collections.

Head of Archives & Special Collections Heather Bidzinski said that the archives, though only an official unit of the university library since 1978, holds records dating back to before the university officially existed.

Bidzinski, the third-ever head in the archive’s history, emphasized the necessity of having archives to look back to.

“It’s important for us to know where we came from in order to make progress in the future,” she said.

Despite working with the past, Bidzinski said that somehow, there’s always something new to be discovered.

“Sometimes you open a box and you’ll find the most amazing pieces of history there.”

Bidzinski highlighted that, fitting for Manitoba and its constituents, part of the archive’s large collection pertains to agriculture. The current Fort Garry campus of the university was originally the site of the Manitoba Agricultural College, which would eventually become the U of M’s faculty of agriculture and food sciences.

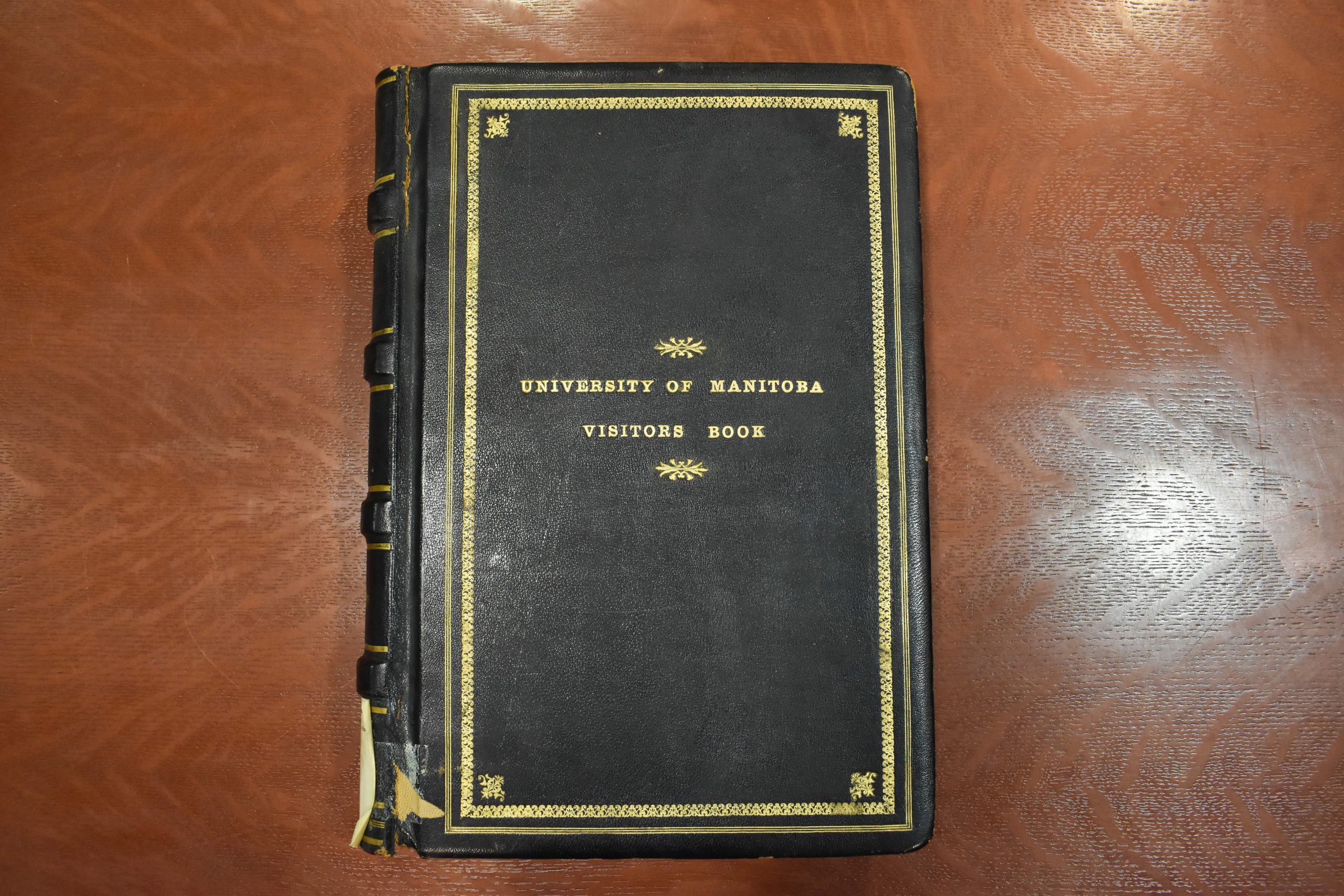

While many items and documents in the archives are digitized, Bidzinski pulled aside some physical pieces from its collections. One visitors book belonging to the archive holds the signatures of major historical figures who visited the university, such as England’s King George V and Queen Mary — then the Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and York — and later, Albert Grey, the fourth Earl Grey and governor general of Canada.

The U of M’s visitor’s book, dated from 1901 to 1920. Many notable visitors came to the university.

Through the archives, one can get a glimpse not only into U of M history, but also into how world history has been observed through the lens of the university, its students and its faculty.

While continuing to offer studies after 1914 in fields such as arts, sciences, agriculture, home economics and law through its sponsorship of the newly founded law school, the U of M added programming to suit the needs of the First World War. The university council established its committee on military instruction, which allowed the teaching of military tactics and science. It also formed a university corps, which organized practise drills, and some students in the corps took extra classes to become officers.

By the end of the war, 1,160 U of M students and 14 staff and faculty had enlisted. Of those, 123 died and 142 received military honours.

“Dinner Time,” 196th Overseas Battalion C.E.F., “Western Universities,” Camp Hughes 1916. In 1915, the Western Universities Battalion was established with the University of Manitoba contributing a company and a platoon.

However, Bidzinski explained that “it wasn’t all business for students.”

During these major events, student activities kept on going. The archives has kept records of student life through well-preserved black-and-white photographs that can only be touched while wearing gloves. For example, Bidzinski showed pictures of the university’s glee club, which was especially active between 1929 and 1940.

Photos also show debate tournaments, football teams, student body councils and regular students just studying outside.

Students from the Manitoba Agricultural College between 1915 and 1920. At this point, the college offered a degree in home economics.

By 1940, however, the university had leased its Fort Garry student residence to the army to serve as barracks for soldiers in training during the Second World War. All 18-year-old male students had to take six hours of military training each week. Approximately 3,600 members from the U of M community served in the military during the war.

After the war, many students who enlisted came back to finish their degrees. At convocation ceremonies, those who served were often highlighted.

“They put their schooling on hold, but would come back and continue their education,” Bidzinski explained.

Through it all, Bidzinski said the Manitoban worked to keep the community informed. Issues of the paper — both hard copies in the archive’s back room vault and now completely digitized versions up to 2012 on the archive’s website — also act as a reference point for the archivists to see the day-to-day lives of students as far back as 1914.

“The Manitoban has always documented life on campus, and it’s been a great source of information since day one,” she said, noting that the publication recorded everything from the social activities of students, like the Freshie Queen contest of 1941, to what was happening on-campus and overseas during wartime.

“It’s interesting for people interested in the history of the university, but also in student activism and journalism and communication in general,” she said.

Front pages of the Manitoban during wartime, depicting its impact on U of M student life.

The archives show some similarities between the present and the past as well. In the same way that the university closed for nearly two years between 2020 and 2022 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in 1918, over 100 years earlier, an influenza epidemic caused a Canada-wide restriction on public meetings and resulted in the closure of the university from Oct. 11 to Dec. 2 of that year.

Similarly to the past few years, the 1918 closure made it so that grading and instruction methods had to be re-evaluated, and students relied on city and student news sources to inform themselves. The closure also required those at the university to incorporate relatively new technology in their learning, which in 1918 meant the telephone.

The editor of the Manitoban at the time wrote of this period that “our mail from the registrar lay unopened on our desks [and] our homework suffered in the interests of journalism.”

Bidzinski expects that when people want to look back on recent years, they’ll look through digital records like website captures and messages from the university president.

She is confident that those connected to the university community will be eager to know what the goings-on on campus looked like during any historically important period of time.

“I think that there will be an appetite to study those major events going forward,” she said.

Bidzinski encourages students to come and visit the archives on campus, open Monday to Friday, from 8:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m.

“Although we can be a challenge to find, I think it’s really an untapped treasure within the University of Manitoba,” she said.

“I hope that students will come by and say hello and see what we have here.”