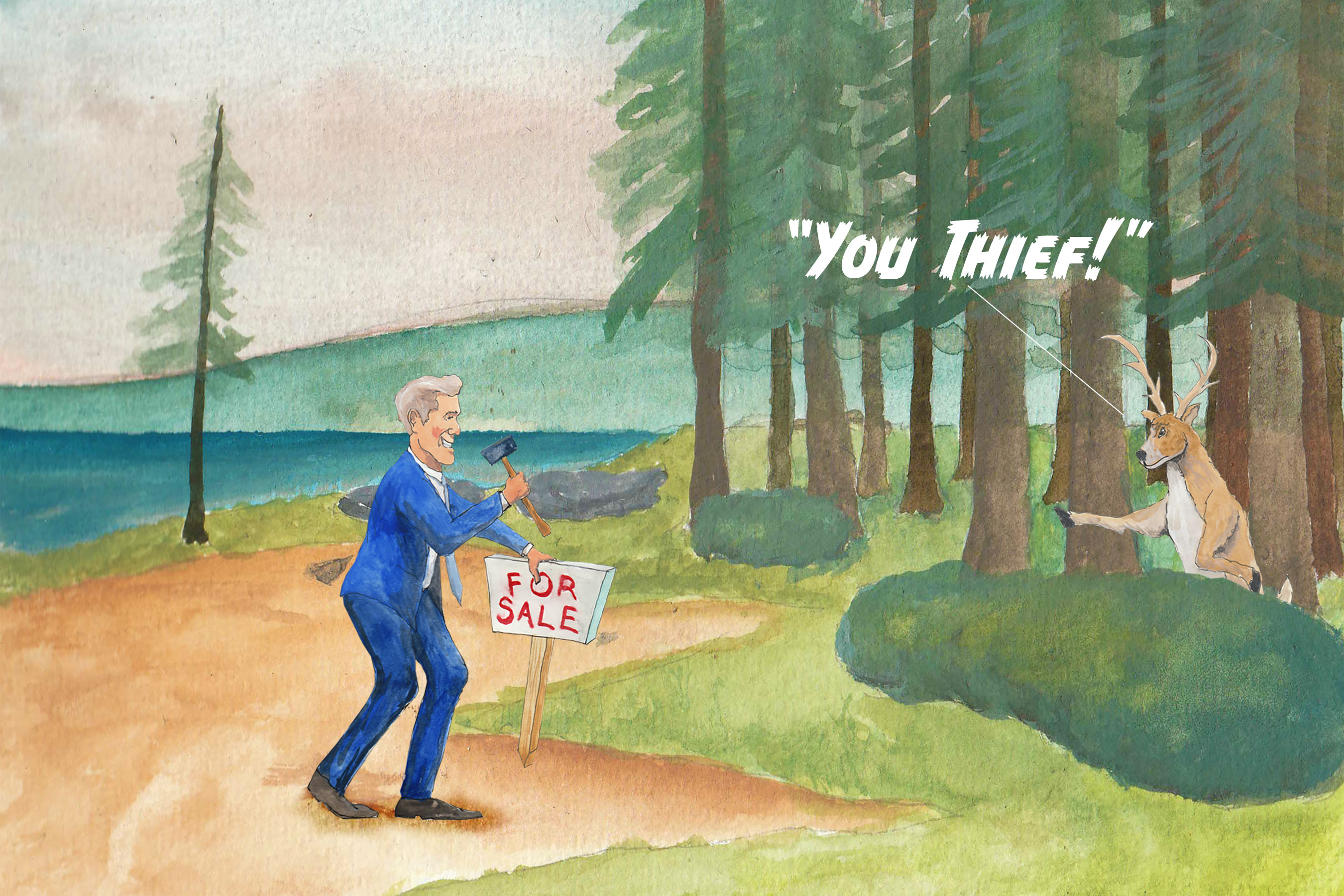

Premier Brian Pallister and the Progressive Conservative Party of Manitoba have issued a request for proposals (RFP) on how to start privatizing Manitoba’s provincial parks.

As of Oct. 13, the RFP is seeking to evaluate 76 of the province’s 92 provincial parks and has emphasized public divestment.

The winners of the bid will also be responsible for assessing the profitability of the parks from a business perspective.

The RFP calls for options to create new tourist attractions such as water parks, amusement parks or hotels within the protected parks themselves.

The province seems to have forgotten that provincial parks are not businesses, and nor should they be.

Protected eco-zones such as our provincial parks are meant to be havens of nature buffered from, in most cases, potentially destructive human development.

This land is not simply idle waiting for private investment interest — it is protected under principles of conservationism.

Although many provincial parks entertain limited levels of infrastructure for economic development as long as it does not disturb the integrity of the park’s natural surroundings, can we really trust private businesses to follow strict regulations? Especially considering regulations may be overseen by an austerity-driven government bent on cutting public necessities.

Beyond this, private interest is wholly concerned with one thing — profit.

This means that cutting both costs and corners is inadvertently encouraged by the ethos of business.

Personally, I have always opposed conservationism. Conservation necessitates human desire to enjoy and exploit nature in various capacities.

Instead, advocating for models of preservation — which do not account for human desires, but rather places the integrity of habitats first — should be the norm for our cherished provincial parks.

But now, under the Pallister government, the principles of conservationism seem like a dream lost to a cold splash of water thrown over your face mid-sleep — worse, perhaps a scalding-hot cup of coffee.

If you have your suspicions about private interest in our provincial parks, your anxiety is well-founded.

In May, the Wilderness Committee discovered a mining claim in Nopiming Provincial Park where mining and economic development was strictly prohibited. Areas had been subjected to destructive mineral exploration, which overlapped with hectares of protected forest that are home to threatened populations of boreal woodland caribou and supposedly a rare pair of trumpeter swans who are formally classified as an endangered species in Manitoba.

The mining claim would have seen this habitat bulldozed for the extraction of plain rocks. Soon after, the committee called for all industrial activity to be banned in provincial parks. And rightfully so.

Greed and profit have no place on the little protected land we have left — especially when that land is home to vulnerable populations or species.

The rights of private conglomerates do not rule on common land. There is no reason why we should allow our government to throw away our collective responsibility to these parks for a couple of bucks.

Further, privatization of provincial parks could throw consultations with Indigenous leaders, who typically play a central role in the direction of park policy, by the wayside.

The privatization of provincial parks resembles the historic enclosures of common land.

Everywhere from Mexico to Nigeria, Vietnam to New York, India to the Amazon, land and people have been subjected to the colonial method of common enclosures and the establishment of dispossessive private property rights.

In every example noted, Peter Linebaugh, a prolific historian, has outlined the principle tendency for planetary woodlands to be destroyed for commercial interest and the tendency for Indigenous populations to be silenced as resource exploits are extracted.

Pallister’s move to privatize provincial parks embodies this history in many indirect, but nonetheless, concerning ways.

I cannot imagine that our parks will be protected when the government is actively advertising them as opportunities to make money. And I certainly can’t imagine private interest consulting with Indigenous communities before desecrating the parks in the empty name of development and business.

With the government in fiscal turmoil after the devastating economic impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, Pallister, and the provincial government, is looking for every opportunity to double down on his radical agenda to privatize and gouge public resources.

And, in this case, privatize and gouge a public resource that shouldn’t even be considered property in the first place.

This may be a harrowing lesson to our management of environmental policy — nature’s gifts are not our own just because we believe we own them.