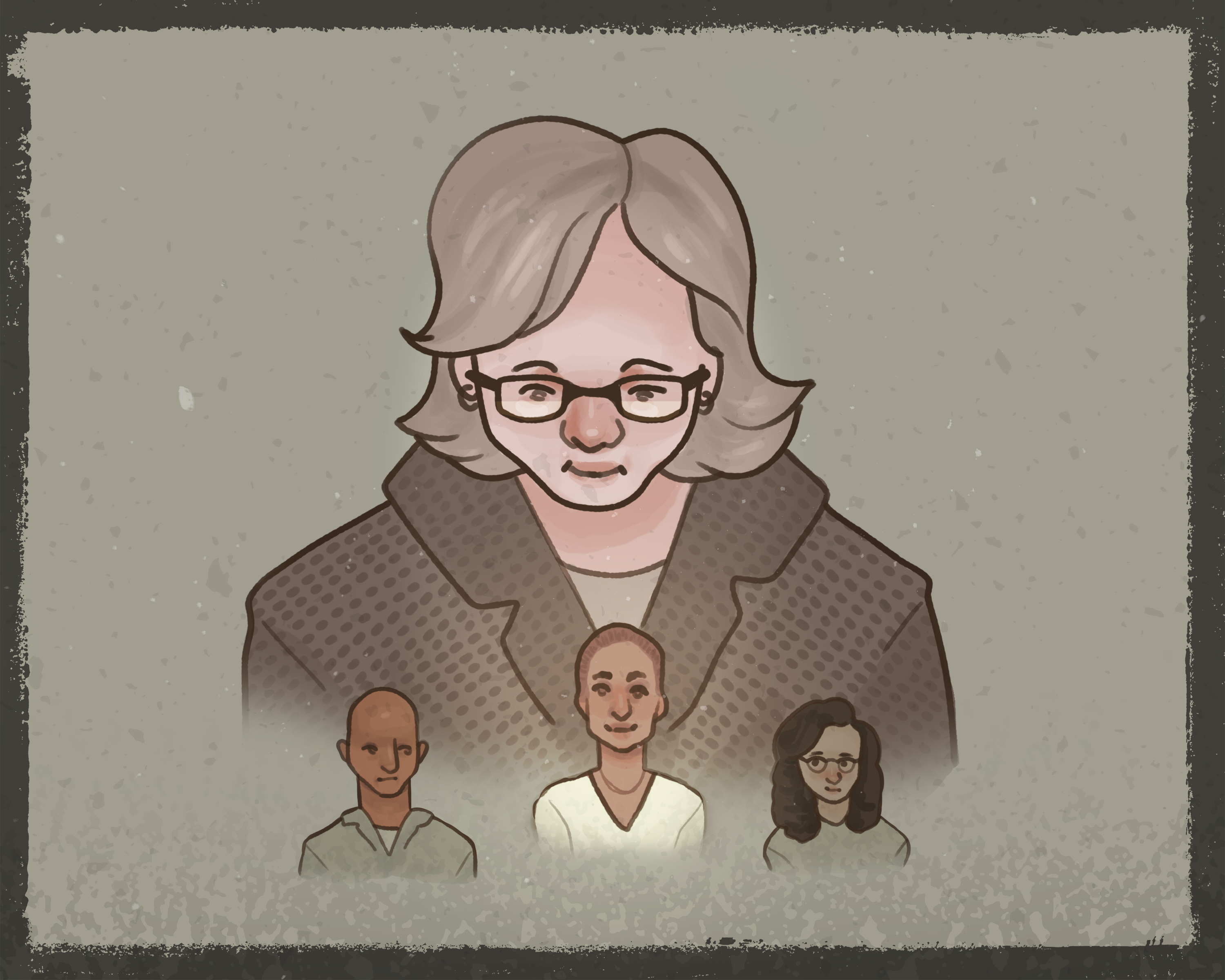

The Green Party of Canada’s leadership race concluded Oct. 3 and Annamie Paul has officially taken the place of the previous Green incumbent, Elizabeth May.

This was a rather narrow victory over Dimitri Lascaris, a provocative candidate who sought to abandon the liberal jargon that the Green party had adopted last election.

May’s attempt at expanding the Green’s support base with the slogan “Not left. Not right. Forward” left voters scratching their heads and ultimately failed to inspire the movement it was pushing for.

Instead, the leadership race witnessed a plethora of strong candidates such Lascaris and Meryam Haddad who were committed to full political transparency. If either of these candidates were elected to leadership, voters knew they would adopt an eco-socialist agenda to combat climate change and democratize the economy.

It seemed that the eco-socialist candidates posed a particular threat to the centrist position the Green establishment had taken since May first assumed leadership of the party in 2006.

For the past 14 years, the Green party has been more inclined to adopt shallow policies to combat the deepening crisis of climate change. Included in May’s plans were policies like carbon taxes and other market-based solutions which depend on uncertain corporate co-operation for any real climate change mitigation.

Paul’s stance resembles this pattern of liberal reform within the confines of capitalist bureaucracy, and the Green party may be rendered redundant in the coming election — an election where Canada so desperately needs a party to separate from the pack-and-push-forth radical policy in pursuit of a green-focused agenda.

Perhaps the Green establishment isn’t really pushing to inspire a generation to help mitigate global warming.

If it was, you’d think it’d be in a bit more of a rush.

It’s almost as though the party is trying to appeal to the voting base of the party in power in pursuit of its own ends —maybe catch a few crumbs while the Liberal Party of Canada bites down on the toast.

But you would think separation from one of Canada’s main parties would be desired — after all, the Liberals have precedent and if the Greens are offering similar policy, why vote for candidates in a marginal party?

The Green party would do better to appeal to voters interested in radical solutions. Policies that emphasize systemic change over reformism are popular, but there are little to no legitimate parties for voters to representatively express this desire with their ballot.

At climate change strikes, all protesters seem to chant is advocacy for systemic change, indicating that the Greens need to open their ears and listen.

One of these two unapologetically socialist candidates could have won and turned the party around had it not been for internal power moves in the race.

Haddad, a Syrian-born bilingual lawyer and candidate for Green leadership, expressed a concern for severe party tampering in the race.

Just weeks before Paul was announced leader, Haddad had been undemocratically expelled from the race for supposedly violating bylaw 1.3.2 of the Green Party of Canada’s constitution. The bylaw cites, vaguely, that contestants may be expelled from the party if they act in any way that could damage its image. In line with this, section 5.2 of the 2020 Green Party of Canada leadership contest rules outlines that contestants can be expelled for violating the party’s constitution — these two clauses essentially provide the party impunity to rid the election of candidates they are not in agreement with.

Haddad appealed this alleged violation by citing a breach of procedural fairness and was reinstated into the race 48 hours later.

Lascaris also faced restraints from the Green party. After submitting to run, his applications were rejected by the party. After appealing the decision, and help from significant pressures from his supporters, the decision was overturned.

Beyond this, May dedicated herself to fundraising for Paul, leaving other candidates in the dust with political contributions.

Thanks to May, Paul recorded nearly $121,000 in campaign funds, according to a report from the Canadian Press.

The closest another candidate came to this was Lascaris who only received roughly $52,000.

This is especially controversial considering May had claimed she would stay neutral in the race.

After several difficulties with email balloting for several candidates, it was enough for Haddad to publicly denounce the Green party race and doubt the integrity of the final results.

Was it any stretch for Haddad to do so?

I think not.

The Green party is clearly displaying a lack of democratic rectitude, promoting a candidate to fit the agenda that May has promoted for over a decade.

But what this race has clearly displayed to voters, over all else, is that the Green party is internally split. The only thing both sides seem to agree on is that fact that climate change is bad.

Unfortunately for the Greens, this spectacle does not look good. Fundamentally, there is no technical solution for climate change, nor is it borne from a lack of economic resources — at its root, climate change is a political crisis.

There is simply no political will and no solidarity as to how to solve it.

So, I pose this question to the Green Party of Canada: how can we trust you to be the leading voice against the largest crisis in human history if you are unable to internally agree on basic political policy?