Historically, the Mennonite presence in Manitoba has been of some significance but, aside from deserving credit for this province’s excellent agricultural record, what does it mean to have Mennonite heritage in this day and age?

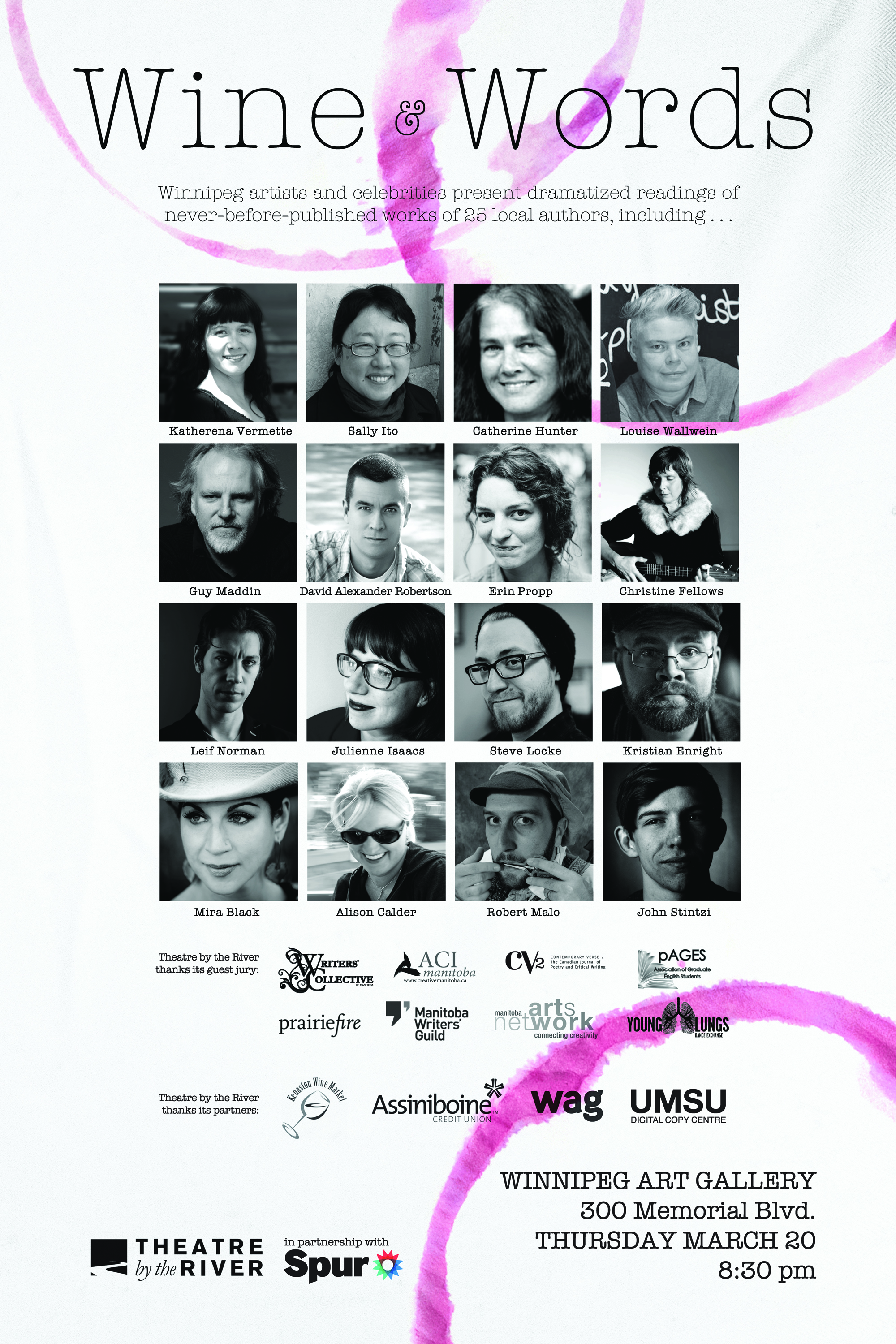

Drawing from his experiences growing up in Steinbach, Man., author Andrew Unger provides a window into rural Mennonite life today through his writing.

Unger is the mind behind The Daily Bonnet, a satirical digital publication focusing on Mennonite life in rural Manitoba. Having grown up in a rural Mennonite context myself, Unger’s short articles for The Daily Bonnet made me feel understood and appreciated, even as they poked fun at everything familiar to me.

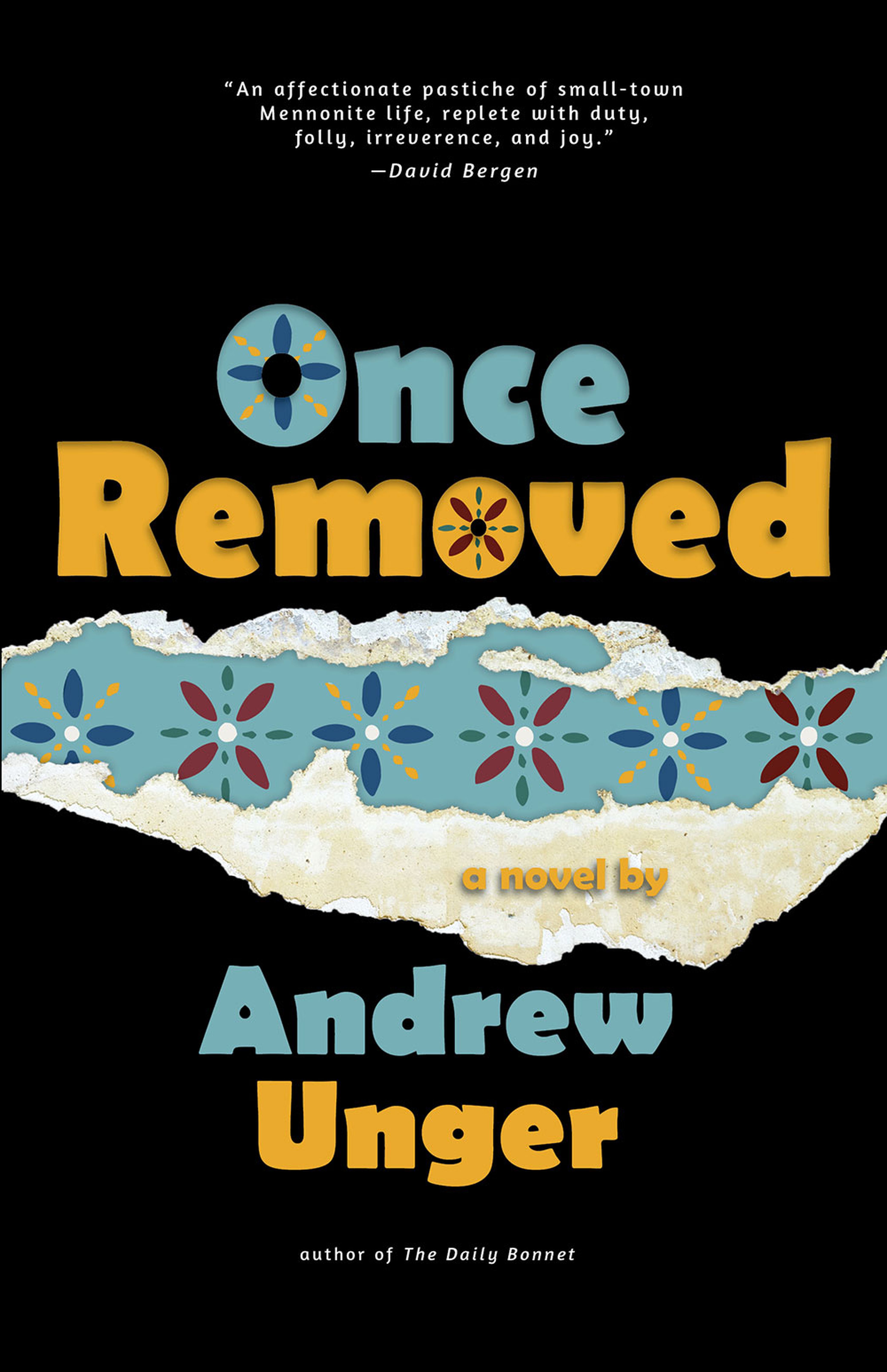

Once Removed is Unger’s debut novel, which is set against the backdrop of the fictional community of Edenfeld in southern Manitoba.

Timothy Heppner is a frustrated ghostwriter whose prospects appear to be drying up. The mayor is on a mission to modernize, and Timothy’s loyalties are divided between the local Preservation Society and his desperation to keep his job with the parks and “wreck” department, tearing down the very buildings the society works to save.

When hired to write a history of the town, he is caught up in the world of small-town politics and must find his voice in order to tell the story of Edenfeld: past, present and future.

Once Removed makes use of the rural Mennonite context to explore the tension that inherently exists between plain talk and propaganda, personal and professional pressures and progress and preservation.

From the set-in-their-ways church elders to the “assimilated Mennonites” of late, and everything in between, Unger’s portrayal is filtered through a humorous and critical lens without malice. The food, genealogical obsession and loss of language shared by these characters reminded me of home and family continuously throughout.

Low German, or Plautdietsch, words are used throughout the novel. Thrown into the middle of English sentences, they are often employed to drive a point home and are mostly understandable from context.

Timothy speaks very little low German, as does most of my generation, and I found the disconnect he felt as a result of this relatable. While I may disagree with Unger as to how some low German words are spelled, and which sides of the river are jantsied and ditsied, even this discord is accurate to the variances in rural Mennonite life across southern Manitoba.

The Mennonite towns of southern Manitoba today are, themselves, once removed from the town of Edenfeld: you will seldom find a housebarn within town limits. Regardless, Unger provides a broad-strokes depiction of rural Mennonite life, and if you grew up in any Mennonite context, you will find something you relate to.

The exposition throughout the novel, however, is not overly explanatory, so if you lack this background you will find there may be gaps in your understanding.

The themes of this novel, progress versus preservation, finding your voice and identifying where your loyalties lie, are universal. Unger addresses them with humour and tact, using the Mennonite context as an effective vehicle.