Whether it is a takeout container from Degrees or the remnants of your lunch packed from home, one thing is certain: at the University of Manitoba, all of these products are ultimately headed to the trash bin.

Ahead of a comprehensive waste audit scheduled for release later this year, students, faculty and the broader community should be asking what the future of waste collection is on campus and how we can work together to reduce our carbon footprint at a campus that is big enough to amount to Manitoba’s third largest city.

According to the U of M sustainability office’s 2014-2015 annual report, the institution has committed itself to sustainability and aims to “minimize pollution, conserve resources, [and] reduce the production and release of greenhouse gas emissions.”

Furthermore, the university food systems workshop group identified composting solutions on campus as a major goal in 2015-2016. Finally, it noted that a significant percentage of packaging used in Campo in University Centre is compostable and biodegradable, albeit with no receptacle on campus.

Anna Weier, the sustainability engagement coordinator from the Campus Sustainability Office, told the Manitoban that there was no comprehensive composting program on campus.

Weier also noted that there was there was no available information from campus eateries regarding rates of diversion for organic materials nor any facilities on campus where one could compost. Weier indicated that further information on rates of diversion and the potential future of composting strategies on campus would be released in February, as part of a comprehensive waste audit.

While the university is now studying the issue, the University of Manitoba Students’s Union (UMSU) has already taken some action.

Campus businesses run by UMSU currently compost via contract with a local waste solutions business. While UMSU does use compostable takeout materials that dissolve faster than regular take out materials in a traditional landfill, there is no post-consumer program offered by UMSU or the university at the current time.

Why is it that the university has no comprehensive plan for composting on campus, which would work to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and pre- and post-consumer waste?

Despite successful pilot programs on the Bannatyne Campus with food provider Aramark, there has been no move to reduce waste system-wide, something that is a troubling fact considering there aren’t even any composting receptacles situated alongside existing waste and recycling facilities.

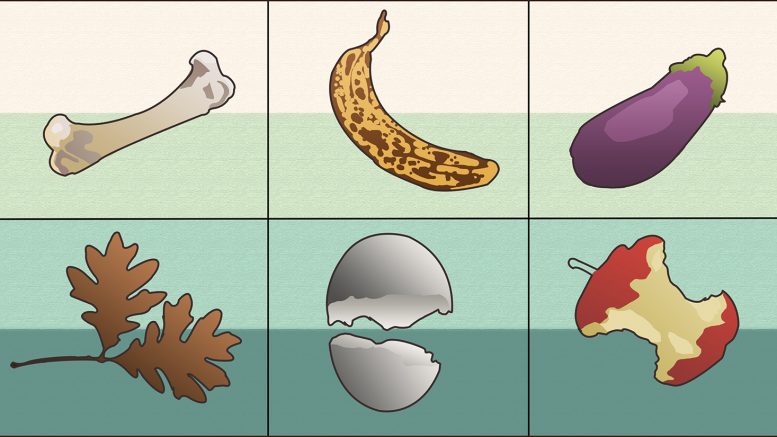

Why does this matter? Do a few table scraps thrown into the garbage really make that big of a difference? The answer is yes. When organics end up in landfills, they often get sealed in pockets beneath other layers of garbage. When this happens, oxygen is unable to reach the organics and it can then take an additional 25 years for the materials to break down.

Additionally, because organics in landfills break down without the aid of oxygen, they end up releasing methane gas into the atmosphere, an emission that is approximately 25 times more harmful than regular carbon dioxide emissions. If we’re going to be serious in the fight against climate change, it’s clear that we have to look at all sectors for ways to reduce our footprint and carbon emissions, especially on the local level.

For example, in Manitoba, greenhouse gas emissions (GHGs) have been on a steady uphill climb for over 20 years.

Through improving access to composting, however, we can diminish waste and reduce harmful methane emissions. According to documents from the Manitoba government, Manitoba could divert 100,000 tonnes – composed of approximately 60 per cent food waste and 40 per cent of leaf and yard waste – of total organic waste annually from landfills by 2020. This diversion would be the equivalent of reducing GHGs by 59,000 tonnes annually. Truthfully, this is a small step. Manitoba has been releasing approximately 20 megatonnes of GHG emissions every year for the last decade. However, it is still movement in the right direction.

We often look at universities as models that the public should emulate on a wide variety of issues. substantial step forward. Certainly, institutions like the University of Winnipeg, through the work of their campus sustainability office, have taken a lead in this regard.

Their office publishes an annual report, auditing waste practices on campus and showing progress in their efforts to promote a more sustainable campus. According to their 2015 report, the U of W composted 36 tonnes of organic material for the year.

While the progress is substantial, seeing as there existed no recorded composting capacity a decade ago, there is still much more work to be done as the total tonnage that ended up in landfills also increased over time. The question arises: what the University of Manitoba can do in the short term.

The U of M is a major contributor to the provincial economy, but what we need now more than ever is for our public institutions to play a greater role in the transition to a green economy. Ahead of the aforementioned waste audit coming in the months ahead, students, faculty, and the general public should be pushing the university to take major steps towards this transition.