In August, Tragically Hip frontman Gord Downie used the band’s final show to try and light a fire.

With the eyes of nearly a third of the entire country on him, Downie directly called on Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to make good on promises he made to Canada’s indigenous communities, which include supporting the ongoing efforts toward reconciliation.

“It’s going to take us 100 years to figure out what the hell went on up there, but it isn’t cool and everybody knows that,” Downie said to a live crowd of around 7,000 people, in addition to the more than 11 million Canadians who tuned in through television, radio, or digital sources.

Now, he is adding fuel.

In Secret Path, a project to be released Oct. 18, Downie tells the story of Chanie “Charlie” Wenjack, a 12-year-old Anishinaabe boy who ran away from the Cecelia Jeffrey Indian Residential School near Kenora, Ontario in October 1966.

Seven days later, he was found dead of hunger and exposure more than 60 kilometres away, by the side of Canadian National railway tracks.

Reports of physical and sexual abuse were common in the Canadian residential school system, which saw indigenous children removed from their communities to be schooled and assimilated in government-funded, church-run schools for more than 100 years. The last residential school closed in 1996.

Reports of children running away to escape abuse were common. Wenjack told his friends he wanted to see his father.

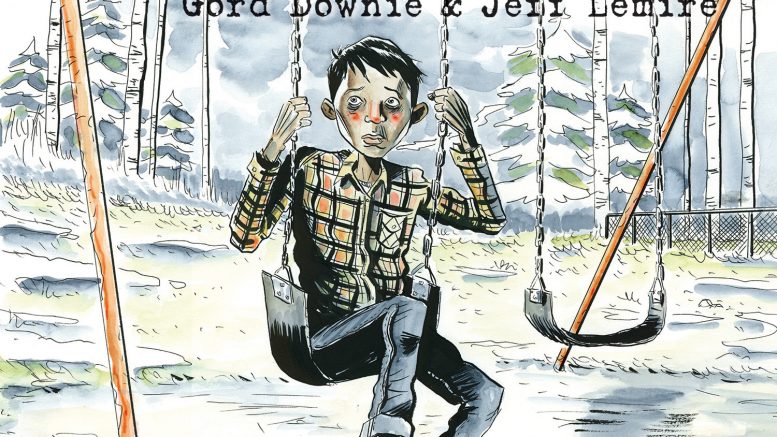

Through a 10-song solo album, an animated feature, and a graphic novel illustrated by Jeff Lemire, Downie lifts the veil on a story that is only a part of what National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation (NCTR) director Ry Moran called a misunderstood history.

“What we are trying to come to terms with as a country is a very long and complicated history that has not been understood – that is not understood – but requires the engagement of all Canadians to right the wrongs of the past,” he said.

“So when somebody like Gord shines his light, uses his voice, to call other Canadians to attention on this very real part of our fabric of who we are as a country, it’s very, very powerful. And exactly what we need to see happening not just once, but time and time again.”

In a release issued Sept. 9 from Ogoki Post, a remote fly-in community in northwestern Ontario, more than 600 kilometres north of Kenora – the home Wenjack was trying to walk to when he died – Downie called Wenjack’s story Canada’s story.

“Chanie haunts me,” he said. “His story is Canada’s story. This is about Canada.

“We are not the country we thought we were.”

Moran met with Downie and his brothers in Ogoki Post to present the project to Wenjack’s family, who still live in the community on the north shore of the Albany River.

“It was a very emotional experience,” said Moran. “It is a very powerful piece of work. Gord has really captured, I think, a very difficult part of our history in a very meaningful way.”

“Gord had the opportunity to share his work with the family and do it in a good way and a really meaningful way and I think in a way that was, in many ways, what reconciliation is all about,” he said.

All proceeds from the album and novel will be directed to the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, hosted at the University of Manitoba, through the Gord Downie Secret Path Fund for Truth and Reconciliation. The fund will support the centre’s initiatives related to missing children and unmarked burials.

The NCTR, which opened its doors on the U of M Fort Garry campus in the summer of 2015, was created to ensure the memory and legacy of Canada’s Indian residential school system aren’t forgotten.

Moran said the support will give a valuable boost to the centre, which recently announced a partnership with the University of British Columbia (UBC) for its Indian Residential School History and Dialogue Centre (IRSC).

UBC hosted the National Event of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in the fall of 2013 and suspended classes for the day so all students and faculty could participate in opening-day activities. Moran said thousands of people participated in the three-day event, striking the collaborative relationships that led to the dialogue centre.

The IRSC will focus on the experiences of indigenous peoples in B.C., where many residential schools were located, and is the first of what Moran said will be a collaborative, nation-wide network of resource centres “to make sure that local communities have the full benefit of being able to participate fully in these conversations.”

“They are different indigenous cultures,” he said. “There’s different historical realities. There’s different nations, even within our own country, and being very responsive and understanding of that is really important in this overall journey of truth and reconciliation.”

Moran said it is crucial to host regional dialogues, and to preserve and open up access to local information, to bring reconciliation to the national level.

“None of this can happen by any one person, it can’t happen by any one organization,” he said. “We need a collective, national response to this. So the more partners we can work with – and the more Canadians that pay attention to this – the better for everybody.”

The conversations will not be easy, he said. And some people will have to be open to feeling uncomfortable.

But in the end, Moran said, knowledge is key and having a voice like Downie’s draw attention to a story like Wenjack’s will bring new voices to the discussion.

“I think what we saw happening in that concert was Gord realizing the power that he has, the power of his voice, and the need that we have as a country to rally around righting some very real past wrongs,” he said.

“I think Gord using his voice in that way was powerful and really was a gift to the country because it brought a lot of people into the conversation that perhaps hadn’t been in the conversation beforehand.”

Gord Downie’s Secret Path album and graphic novel will be available Oct. 18. An hour-long animated feature, The Secret Path, will be broadcast on CBC television Oct. 23.