In its hundred-year history, the Manitoban has been the first step on the way to a professional career for numerous writers. But there is one who leaves them all behind, whose association with the Manitoban gives us instant respectability even with those who sneer at the student press. I speak, of course, of Marshall McLuhan.

McLuhan did his undergrad and master’s in English at the University of Manitoba in the late 1920s and early 30s. During this time he was a contributor at the Manitoban, writing articles on literary and political issues and editing the literary supplements.

McLuhan grew up to be a new breed of academic. Though very traditionally trained in English literature—he did his doctoral work at Cambridge, tracing the history of grammar, logic, and rhetoric up to Thomas Nashe—his main interests lay elsewhere. For McLuhan, the most significant cultural artifacts were the popular media to which the academy was mostly blind. These interests were revealed in his first published book: The Mechanical Bride: Folklore of Industrial Man.

In this book, McLuhan analyzed newspapers, comic strips, and especially advertisements. His analyses display considerable erudition, but McLuhan did not develop his points along traditional lines. Rather than making any kind of linear argument, he wrote mini-essays that can be read in any order, each of which gives a different perspective on the nature of media and social construction in an age of technology and mass communication.

The result is a fascinating read in its own right, somewhat reminiscent of Montaigne – if Montaigne used 1950s slang. More interesting than the unusual form is the way McLuhan cuts to the core of the collective psyche of industrial capitalism.

The title essay is an analysis of an ad for stockings featuring a woman’s legs standing on a podium with the rest of her body out of frame. McLuhan argues that this ad portrays the legs as interchangeable parts – a cultural obsession in industrial society, he says. “Ads like these not only express but also encourage that strange dissociation of sex not only from the human person, but even from the unity of the body.”

More generally, he says, a pattern in popular culture and advertisements is “the widely occurring cluster image of sex, technology, and death which constitutes the mystery of the mechanical bride.” Advertisers take these images and use them to turn the ordinary sex drive into “a metaphysical enticement, a cerebral itch, an abstract torment.”

McLuhan thought that the extent to which our basic attitudes and beliefs are constructed by advertisers rendered direct resistance futile. The miasma of media and commercials constitutes an education system in itself, he believed, and it has much more money and power behind it than academia. Therefore, it is necessary to use pop culture’s weight against itself by presenting, studying, and reinterpreting the powerful images it creates. The best way to approach these things, according to McLuhan, is with amusement, not anger.

We live in a world of even more advanced technology than McLuhan’s 50s, operating faster and on a larger scale. Popular culture has fragmented into a million pieces. Advertisers are sophisticated and intrusive. Our political media is louder and larger than ever but seems strangely arbitrary and pointless. In such a world, the insights of McLuhan become even more significant.

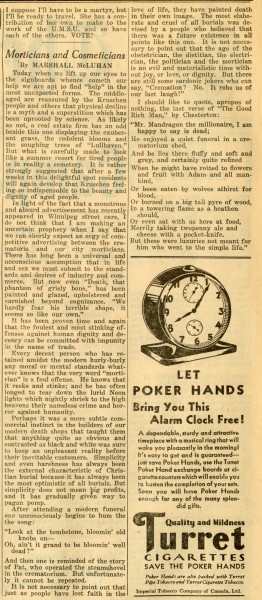

We have reprinted for your reading pleasure an article McLuhan wrote for the Manitoban in 1934, entitled “Morticians and cosmeticians.” In addition to being a marvellous early example of his allusive and elusive writing style, it deals with issues related to the topics addressed in The Mechanical Bride.

This article first appeared in the March 2, 1934 edition of the Manitoban. The advertisement which inspired it is, unfortunately, lost to history.