Joshua Lindal, an anthropology PhD student at the University of Manitoba, is part of a research team that has proposed a new species name for a human ancestor that lived half a million years ago. Unsatisfied with the monikers of Homo heidelbergensis and Homo rhodesiensis, Lindal’s research group has argued for their retirement. In their place, the group advocates that many H. heidelbergensis fossils be grouped with the existing Homo neanderthalensis and H. rhodesiensis be reclassified into a new group called Homo bodoensis.

Lindal has been working with a group of researchers studying early human ancestors. The group includes Mirjana Roksandic, professor in the department of anthropology at the University of Winnipeg, and Predrag Radović, research assistant in the department of archaeology at the University of Belgrade.

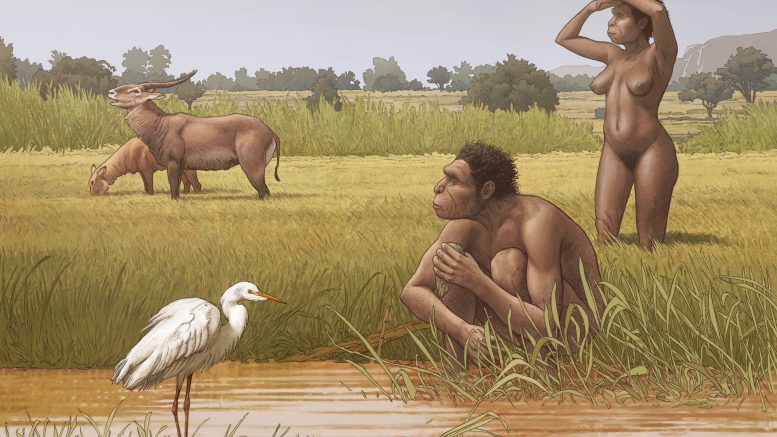

“We used to think about this straight line from Homo erectus to archaic humans to modern humans today,” Lindal said.

“And now we’re realizing that of course, it’s way more complicated than that.”

Our species’ lineage is by its very nature exploratory. Early humans covered more land than previously expected, meaning conceptions of discrete proto-human species may not be as accurate as once thought.

H. heidelbergensis got its name from the city of Heidelberg, Germany, where a workman found a fossilized mandible in 1908. The mandible had traits of both Homo erectus and Homo sapiens, so scientists declared it a new species. The authors argue paleoanthropologists have tended to categorize most fossils from this time period under this one species name.

H. rhodesiensis was named after the colonial African state of Rhodesia, which in turn was named after British colonist Cecil Rhodes. The fossilized skull known as “Rhodesian Man,” from which the species was described, was found in what is now Zambia in 1921. However, the colonial history of this name alone is not enough to invalidate its usage, according to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature.

Lindal’s research group has proposed these species names are inaccurate.

In the cases of H. heidelbergensis and H. rhodesiensis, the authors argue fossils from the period are scattered and poorly understood. This has resulted in haphazard designations which have failed to stand the test of time.

The authors argue fossils currently under the designation of H. heidelbergensis that exhibit Neanderthal traits should be reclassified as H. neanderthalensis. Likewise, fossils currently under the designation of H. rhodesiensis should be reassigned to the new designation H. bodoensis.

H. bodoensis refers to the site of Bodo D’ar in modern-day Ethiopia, where the fossil specimen “Bodo 1” was discovered. The new H. bodoensis is situated in time after H. erectus and the most recent common ancestor to all living humans. This would mean that H. bodoensis is an ancestor to H. sapiens, but not H. neanderthalensis.

To understand why specific species names need to be suppressed and others proposed, one must first understand the species problem. Species don’t exist in nature. They are a scientific construct with significant limitations. To preserve the usefulness of this categorization tool, scientists have proposed more than 30 species concepts — or definitions — of the category.

One common conception of species uses the biological species concept, which states that organisms that can interbreed and produce fertile offspring are grouped into a single species. The problem with this conception is that it fails to account for behaviour.

“Like in birds,” Lindal said, “maybe they sing in different mating calls. So, they don’t have sex with each other because they don’t recognize each other as potential mates […] even if they are technically fertile, if they don’t actually breed together, then they’re fundamentally reproductively isolated.”

Ultimately, the deciding factor in determining whether a group of organisms are one species is scientific consensus.

Much of the research leading to this proposed name change stems from fossilized teeth. Lindal’s PhD research focuses on teeth in early human ancestors. Teeth are interesting to scientists because they are harder than bones, are more consistently found at field sites than bones and are under strict genetic control.

“A lot of people probably imagine that all of our biology is under very strict control, but in reality, development will interact with our environment as we grow up and it’ll modify the way our genes get expressed,” Lindal said.

The strict genetic control of teeth allows researchers to track the relationship between Neanderthals and modern humans.

The categorization of hominin species remains hotly contested in part, Lindal argues, because we care more about humans than we do about other animals.

“The paleontologists are like, ‘Why are you splitting hairs on this?’” Lindal said.

“‘They’re all humans, they’re all the same species.’”

“And it’s because we care about humans more than other animals […] so we’re trying to get a better resolution on humans. But in the end, we end up using different criteria for categorizing humans than we use for categorizing other animals.”