The Scientific Revolution during the Modern Age is often remembered for its monumental discoveries, like Newton’s laws of motion and Kepler’s planetary motion. Ideas like these transformed the intellectual landscape of Europe and continue to give physics students an incredibly hard time. Behind all these achievements stood an equally important social institution, the coffeehouse.

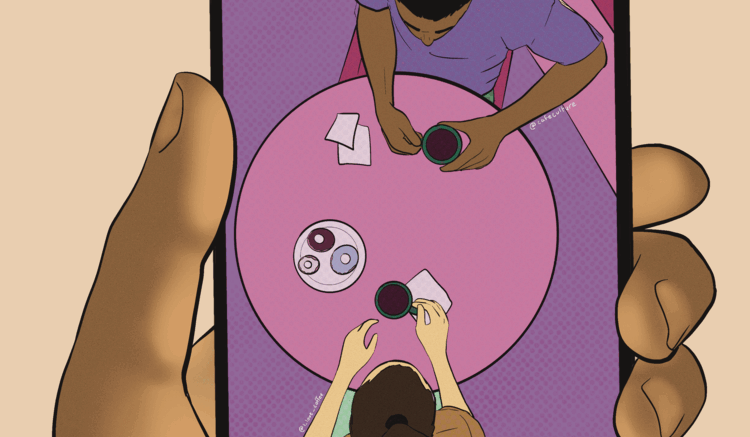

Early coffeehouses attracted a remarkably broad cross-section of society. Merchants, scholars, physicians and philosophers all mingled around shared tables. Unlike hierarchical institutions such as universities or royal courts, the coffeehouse offered a more egalitarian space. I think this openness was crucial because it allowed ideas to circulate more freely across society, rather than being confined to the elites. Anyone who had an idea or was interested in something could partake in the conversation, giving insights and learning from others. The coffeehouse created a space where class was no longer as large an obstacle for free thinking.

Coffeehouses also promoted collaboration. In cities like London and Hamburg, coffeehouse patrons often met strangers, engaged in debates and formed networks that led to scientific, political or commercial innovation. I believe these open gatherings meant that a curious thinker could easily encounter someone with the resources to fund an experiment, publish a pamphlet or support an invention. For example, a merchant might overhear a scientific problem and offer information gathered from overseas trade, or a physician might provide technical insight that reshapes someone’s initial idea. This kind of open collaboration was important because it broke down the barriers that normally kept knowledge siloed within specific professions or social classes. Instead, the coffeehouse allowed ideas to develop collectively, enriched by perspectives and expertise that would never have come together in more formal or exclusive settings.

Beyond science, coffeehouses were arenas for discussing and debating political philosophies. I think this was important because the coffeehouse was one of the first genuinely public spaces for discussing civic life. People were able to come in and truly express their ideas and opinions. And these ideas were open to challenge from others, which created a space for true intellectual growth.

Yet, as is evident now, this golden age of coffeehouses did not last forever.

Now, coffeehouses seem to prioritize commerce, and consumers seem to prioritize convenience. I don’t know about you, but I rarely walk into Tim Hortons or Starbucks with the intention of sitting down and listening to someone speak about their “great ideas.” I tend to walk in, get my coffee and walk out. I think this reflects a broader shift in culture. The rhythm of life is now structured around efficiency and schedules. But this decline in coffeehouse culture does not mean the end for open discussion, collaboration or debate. In fact, the conversations are still taking place, just on social media instead.

While I acknowledge all the good that social media does in facilitating conversations, I cannot help but wonder what our society would look like if we still had physical coffeehouses — the ones where you had to walk into the room, sit down, and be prepared to listen just as much as you were prepared to speak.

There was a sense of accountability that came with being face-to-face with other people. You couldn’t build an echo chamber around yourself. You had to be willing to be faced with disagreement. If you shared insight, you had to be able to defend it. And if someone said something you disagreed with, you had to be courageous enough to challenge them. I think this is what gave political debates and scientific conversations in coffeehouses their unique importance. They were not simply exchanges of opinion, but exercises in civic responsibility.

Our modern coffeehouse, social media, does connect a much larger group of people, but it still misses some of the elements that made the original coffeehouses so special.