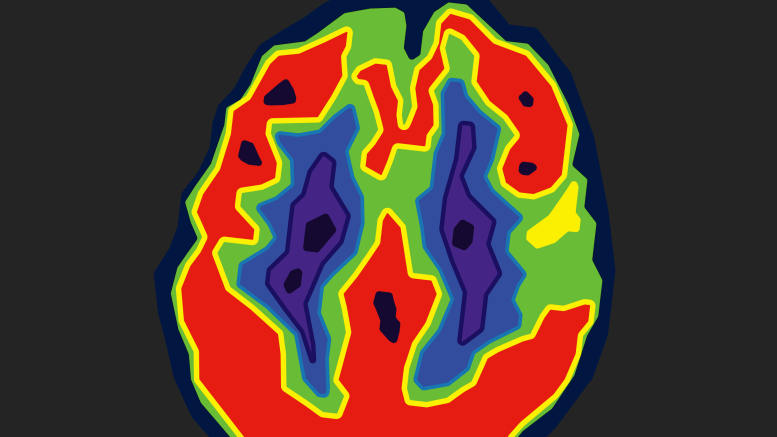

Nuclear medicine involves injecting patients with radioactive substances to create detailed images of their bodies. These images help doctors diagnose various medical conditions.

Sandor Demeter, former member of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission with two decades in clinical nuclear medicine experience, opined that “Nuclear medicine is a fascinating medical specialty.”

Most medical imaging techniques capture structural images of the body by sending energy through the patient in various forms — X-rays for CT scans and radiographs, sound waves for ultrasounds and magnetic fields for MRIs.

Nuclear medicine is different.

“We actually inject small amounts of radiopharmaceuticals, which are handled by the body in a physiologic manner,” Demeter said. “Depending on what we tag to the radiopharmaceutical, we can look at any organ and its function.”

He explained that heart disease and oncology, the study of cancer, are the two largest areas looked at in nuclear medicine. Where other imaging techniques examine the anatomy of body structures, nuclear medicine focuses on physiology, or how those structures function.

After a component of nuclear medicine known as positron emission tomography (PET) was developed, Demeter was instrumental in building Manitoba’s PET scan program. Since then, PET scans have become a standard of care for lung cancer patients.

“A PET scan would change management in lung cancer patients 40 per cent of the time,” Demeter said. “That’s phenomenal.”

“It was much more sensitive in showing where the tumor was, how big it was, had it spread, had it come back, did it respond to therapy — all those things.”

Today, there are two PET scanner machines in Manitoba. Between 15 and 30 patients receive scans every day.

A PET scan begins by injecting patients with a small, safe amount of radioactive sugar. Because tumors tend to consume more energy than normal body tissues, they use up more of the radioactive sugars. This difference in energy usage is displayed on the medical image, helping doctors identify the location and activity of tumors.

“It’s pretty simple,” said Demeter, “but it’s a game changer for cancer treatment and helping people figure out what the best path forward is for their treatment.”

Beyond medical imaging, nuclear medicine has applications in therapy.

“We can inject a small amount of radioactivity that targets the tissues you want to treat,” Demeter said. “It’s very targeted.”

Treatment for thyroid problems, for example, involves having patients drink radioactive iodine, as the thyroid picks up 200 times more iodine than neighbouring cells. New therapies targeting rare neuroendocrine tumors and their receptors are also under development.

Prostate cancer is the subject of promising new research.

A molecular “key” targeting prostate cancer receptor cells can be injected into a patient’s bloodstream. This molecular key will move through the body, searching for and binding to the receptors. Attaching a therapeutic radioactive agent to the key will kill the cancer cells.

This therapy is part of a new branch of nuclear medicine called theranostics.

The term “theranostics” is an amalgamation of the words “therapy” and “diagnostics,” and it describes a process that does both. It uses radioisotopes to first scan a patient’s tumor for diagnosis and then provides targeted treatment for that tumor.

“[These therapies] will be a game changer, because prostate cancer is so common,” Demeter said. “That’s pretty exciting stuff.”

Nuclear medicine is a small specialty, with only seven certified nuclear medicine physicians practicing in the province of Manitoba.

Increasingly, physicians complete residencies both in nuclear medicine and radiology — a branch of medicine which diagnoses and treats disease using imaging technology. Training in nuclear medicine as well as radiology allows physicians to draw more information from a patient’s medical scans, helping them learn about a patient’s health.

“That’s the evolution of the specialty,” Demeter said.