Every once in a while, I receive an email encouraging me to take a survey. Whether it is from the faculty of science or of kinesiology and recreation management, someone always claims to be keenly interested in my thoughts and feelings.

I am sure many U of M students can relate to the constant urging from the university to express their views. Sometimes the university even offers the chance to win prizes to incentivize students to take these surveys. Ordinarily, people are more than happy to share their perspectives, especially if there is a perceived positive result that comes from doing so. However, I believe that now, fewer and fewer people are inclined to take surveys because of the growth in the general feeling that they are a waste of time.

Surveys, simply put, are “an examination of opinions.” The survey givers gather questions to ask the public to examine their thoughts on a matter, and the survey takers answer the questions the way you would an exam, except instead of answering based on academic information, your response is based on your experience.

Universities generally use surveys to better understand their students because of the useful nature of surveys. They collect primary data, often regarded as one of the more effective and accurate methods of collecting extensive information from university students.

Despite this, I think surveys are not useful because of the growing sense that survey givers are disingenuous and do not really intend to use our input. This belief gives students the impression that participating in a survey is ultimately just a waste of time. After all, what is the point of giving your opinion if it is not going to be considered?

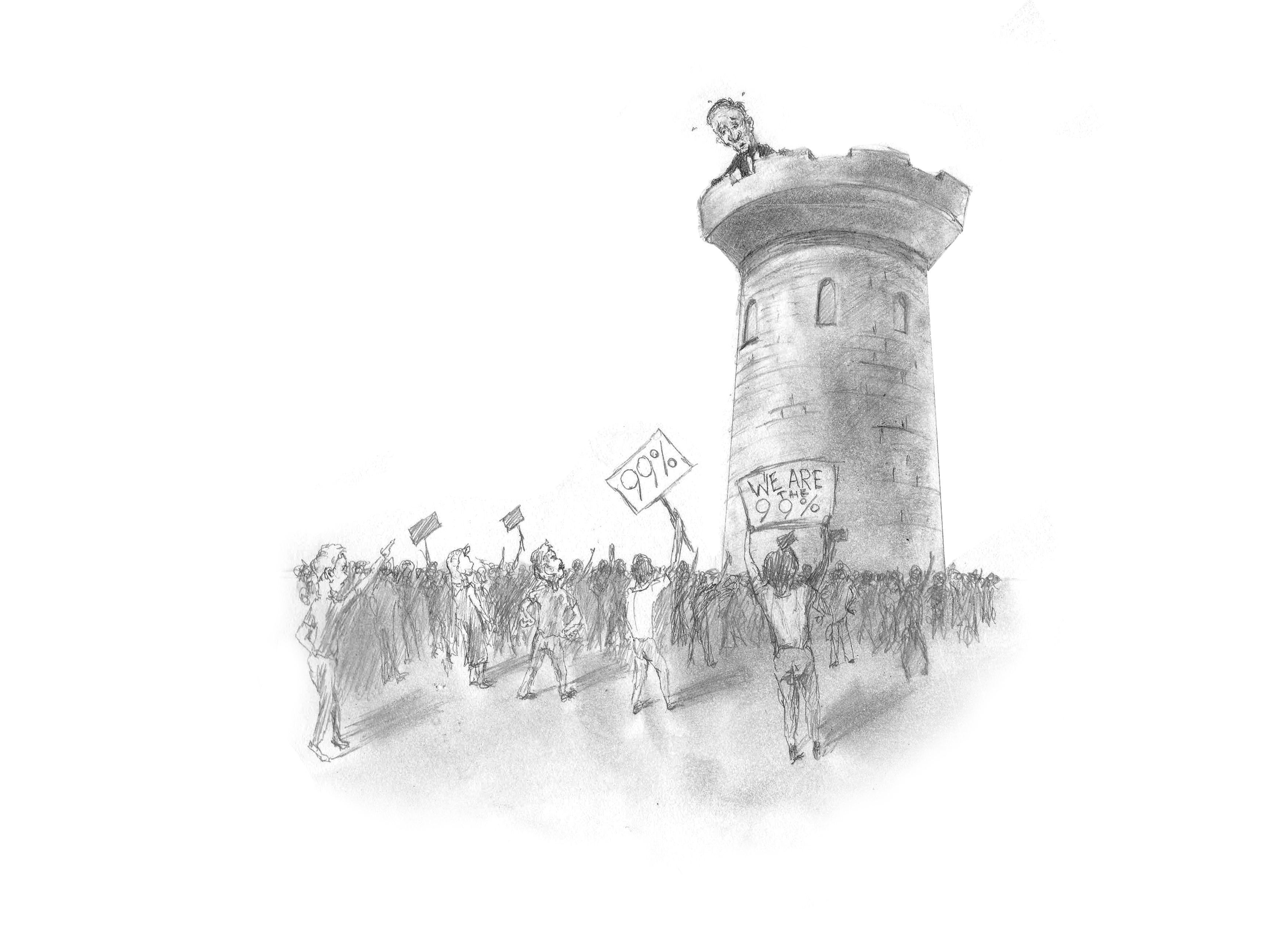

Many people feel that surveys are a way for those in charge to pretend that they care about what the public thinks when, in reality, people’s responses are of no value in any major decision-making discussions. It is as if some surveys are given for the sake of falsely embracing the democratic practice of placing importance on the voice of the people. Universities get to tick the box of caring about the opinions of the public by giving out surveys but then seemingly do nothing with the information they have gathered.

This criticism is further supported by the poor design of some surveys accused of having leading questions. Questions that prompt responders to move toward a certain response. For example, if I asked, “how do you feel about my amazing article?” the question is structured in a way that makes responses lean toward a certain bias, in this case, a positive outlook on my article. Questions like this result in responses that are not honest representations of people’s thoughts and instead only support the intended biases.

Additionally, some questions limit the responses people are able to give. Questions with any form of multiple-choice answers tend to restrict the feedback survey takers can give. The provided options are not extensive enough to encapsulate the true feelings of people and, in turn, limit the options on a survey. This allows the survey givers to have some control of the outcome. While I acknowledge that it is not always possible to have surveys with only open-ended or closed-ended questions, it is important that if options are provided, they are as wide-ranging as possible and have the intention of understanding the people and not controlling the outcome of results.

I believe surveys are a great way for students to give their input on different areas of our university. However, it is highly unlikely that students will see them as a useful way to spend their time until they are convinced survey givers truly care what they have to say.