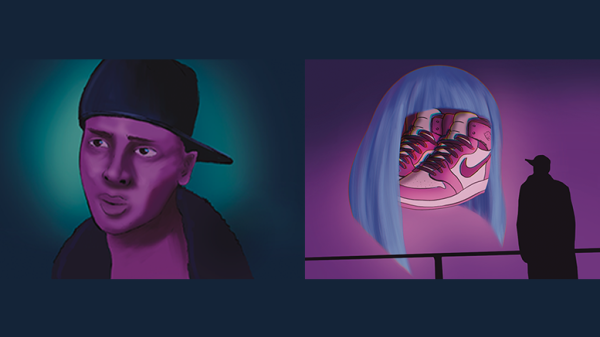

A while back, I was scrolling on TikTok or Instagram. I don’t exactly remember what short-form content medium I was consuming to rot my brain. Regardless, I stumbled upon a video clip of a U.K. rapper Central Cee — most of you know him through allegedly cheating on Madz with Ice Spice — and a U.K. sneaker shopping show.

Most interviews of famous celebrities are quite surface-level, just the basic questions about their upbringing or “what inspires them,” but this time Cee was asked the question of what sneakers he is into right now. His answer piqued my interest.

It went something along the lines of, “It’s too much like, too much like, consumerism.” It pulled me out of my brain rotted trance. At that moment, I started thinking to myself, “he’s kinda right.”

Every summer, there is always the trend of what’s the new shoe or piece that defines the summer. The pandemic piqued masses’ interest in the fashion industry, and many my age have started thinking about such things more deeply. I mean, we did have all the time in the world.

For me personally, a small aspect of my fashion journey started when I was about to enter middle school. It was the end of fifth grade, and murmurings were going around the boys in my class about shoes. I quickly realized I was the odd one out. So, over the summer, I researched and quickly became a fan of sneaker culture.

Before the start of sixth grade, I begged my parents to get me shoes, and they obliged. I went to Foot Locker and got a pair of Jordan shoes. I don’t remember the exact model, but they were reminiscent of the Jordan 3 in cool grey. Needless to say, when I returned to school, I was the talk of the town for about five minutes. Ever since then, I, like many other people, have been chasing that high of fashion validation.

I remember my father berating me for buying something so expensive. At that moment, I started to see the value of shoes as more than a commodity. They hold capital beyond just the price tag.

A pair of Jordan shoes might cost the same to produce, materially speaking, as a pair of Skechers. They’re both made of similar fabrics, and I imagine they have a similar manufacturing

process. Then why is it that the Jordan shoes are held to such a high standard? Why are some products held in a “higher regard,” while others, not so much? Even when the core of them is the same.

Priya Ahluwalia is the creative director and founder of the menswear fashion house Ahluwalia. Through her Nigerian-Indian heritage, she has sought, in my opinion, to answer the same question I had.

On a family trip to Nigeria in 2017, Ahluwalia had noticed that many folks on the streets were wearing distinctively British graphic tees. Later, on a trip to India, she had been informed about the city of Panipat where discarded clothing from the west would be sent there to be dumped, recycled or sold.

For her graduation collection at London’s University of Westminster, she sought to make a collection purely from recycled clothes — and she had gained a lot of buzz. Rightfully so, for her trailblazing work.

Ahluwalia sees the “fashion question” as an environmental question. However, like many questions, fashion consumerism is something to solve by a more concrete understanding through class politics — not the postmodernist drivel of modern interpretations of art and how the masses relate to it.

I don’t mean to be too aggressive or inflammatory towards Ahluwalia — far from it. I am a big fan of her work, but what I wish to highlight is that she is the symptom of a bigger problem that plagues the arts.

My gripe lies in the fact that we could try to solve the conditions of these clothes to be more sustainable, but that would mean nothing unless we can materially change the conditions of those residents of India, Nigeria or any other impacted nation worldwide.

My issue is that while we can work to make clothing more sustainable, it won’t matter unless we also address the living conditions of people in developing countries, who are constantly being affected.

We assign different values to clothes because they are worn by elites whose mere presence elevates them beyond their material worth. The real division in fashion stems from the inequality among people, rooted in class and social standing, which leads to their oppression. Until we solve that core issue, everything else is just surface-level rhetoric. In short, don’t get caught up in idolizing “rags” as I once did. The real value lies in people.