In response to the Sept. 6 article, “Critics Cry Foul Over UMSU Organizational Shakeup.”

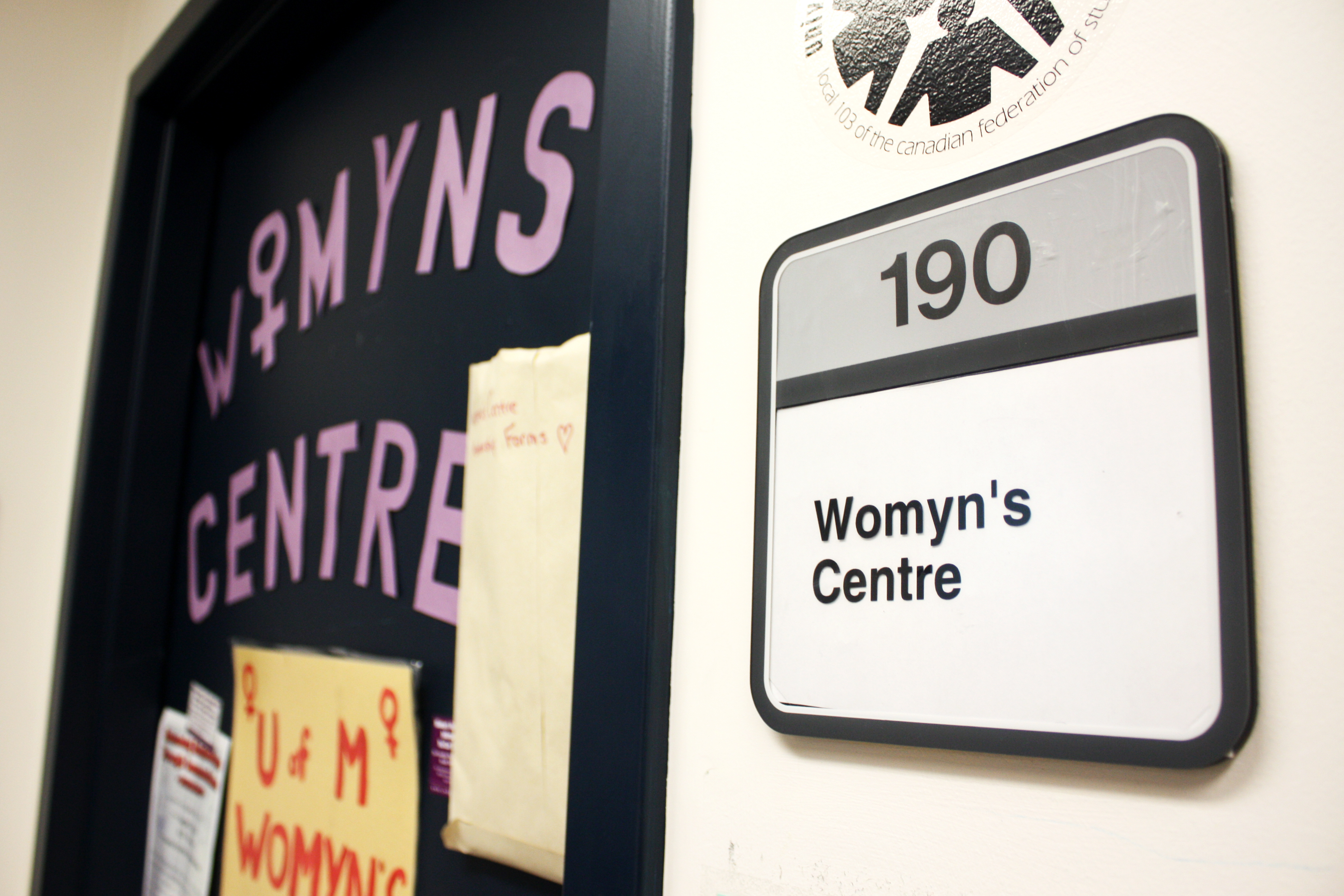

When the Manitoban reported that UMSU has dramatically restructured its service centres – eliminating independent coordinator positions for the Womyn’s Centre, Rainbow Pride Mosaic, Aboriginal Student Association, and Accessibility Centre – in favour of a single coordinator to oversee all four spaces, I was angry but unsurprised.

For now, ignore that this is deeply problematic – assuming, as it does, that the UMSU executive is justified in unilaterally determining the mandate of a service centre as well as whether or not said mandate is being met, all without prioritizing the input of the actual collectives and councils that work out of these centres.

For now, ignore the convoluted logic of claiming to have prioritized the consultation and consent of the elected community representatives relevant to each centre – while at the same time admitting that the coordinators are currently more connected with these communities, as the UMSU executive admits in the Manitoban report on the organizational shakeup.

Ignore the frank absurdity of the notion that replacing four coordinators with one coordinator will somehow create better services and resources at four independent centres.

Ignore all of this because my space here is limited and I have a particular bone to pick.

The UMSU service centres have traditionally been staffed only by those who identify with the communities the centres service: the coordinator of the Womyn’s Centre needs to identify as a woman, trans, or non-binary individual; the Rainbow Pride Mosaic coordinator needs to identify as falling somewhere on the LGBTTQ* spectrum, and so on.

This self-identification matters, not only because the service centres are intended to offer safer spaces – meaning, in part, that if you do not identify with the community that the centre services, you are asked to refrain from using the space – but also because the coordinator role, at its core, is representational.

While there are UMSU community representatives elected to represent community voices on UMSU council, the service centre coordinators represent community voices in the day-to-day operations of the centres. They uphold the community principles of the centres during meetings, office hours, and in the frontline organizational work each centre does with the rest of campus.

Of course, it is perfectly possible for a candidate for the new coordinator position to identify as a member of all four relevant community groups; however, that isn’t the criteria for being hired to this position. As the UMSU executive made explicit, a hireable candidate need only to identify as an “ally” of the relevant communities, and they would receive training to compensate for any gaps in knowledge.

An “ally,” as this sort of discourse understands it, is someone who has learned about oppression, is sympathetic to those who experience it, and has committed themselves to helping those communities overcome oppression. An “ally” puts the needs of people more marginalized than themselves first. An “ally” takes hits for other communities and puts their privilege on the line to create tangible gains. An “ally” understands that knowledge is not equal to the lived experiences of oppression and cedes ground to others who have experienced such oppression in order to amplify their voices.

See the problem yet? To accept this job would mean that you, as an “ally,” believe yourself just as qualified to represent and empower a marginalized group as an actual member of that group. To accept a position that actively erases space – not to mention employment – for the people you purport to represent and empower is inherently anti-ally.

The position is oxymoronic. It is simply impossible to both occupy the position and also justify your proclaimed “ally” status.

In creating this position, UMSU has inadvertently exposed the inherent problem of “ally” status.

“Ally” is the new accountability cop-out. Rather than signifying a commitment to the safety and wellbeing of others, as the term may be meant to suggest, “ally” now represents a much more insidious, bureaucratically-regulated social scorecard. Anyone can claim status as an “ally” and, all-too-often, people do so to re-centre a privileged subject in a space specifically cleared by and for those on the margins.

Don’t identify personally with a community? No sweat, just assure the community that you’re familiar with the issues they face – hell, take up all the space you can to assure them – hell, take their jobs to assure them, why not?

“Ally” is invincible.

Do something that hurts or belittles a community? No sweat, just undergo a formulaic “ally training” and rejuvenate your credentials as a certified “ally.” Will the appointed candidate need a 1:1 ratio of hours served/hours of “ally training” to compensate for the violation of taking this job?

For years, queer and trans, black and Indigenous, and people of colour have been telling us that “ally” is not a noun but a verb – that no one should get to claim “ally” as a status but instead should work each day to demonstrate their “allyship.” This framework prioritizes the action of allyship. That is, doing actual solidarity work without demanding reward, amplifying the voices of others instead of simply taking up space, and being critical of any self-congratulatory rhetoric of “allyship” that allows self-proclaimed “allies” to assume leadership roles in communities that they are not a part of.

This framework insists that “allyship” is active, not static. “Allyship” not a status to be claimed but work to be done. When we refuse to acknowledge these teachings and insist on institutionalizing “ally” as an identity category, the “ally” is exposed as a spectre – the substanceless ghost of an unmet promise to action.

And how do you combat a ghost? Well, you can’t. You just have to tear down the house and rebuild.

In this case, UMSU is the house.

Jennifer Black was the 2010-11 UMSU women’s representative, 2012-13 UMSU VP advocacy, and a former UMSU Womyn’s Centre coordinator.