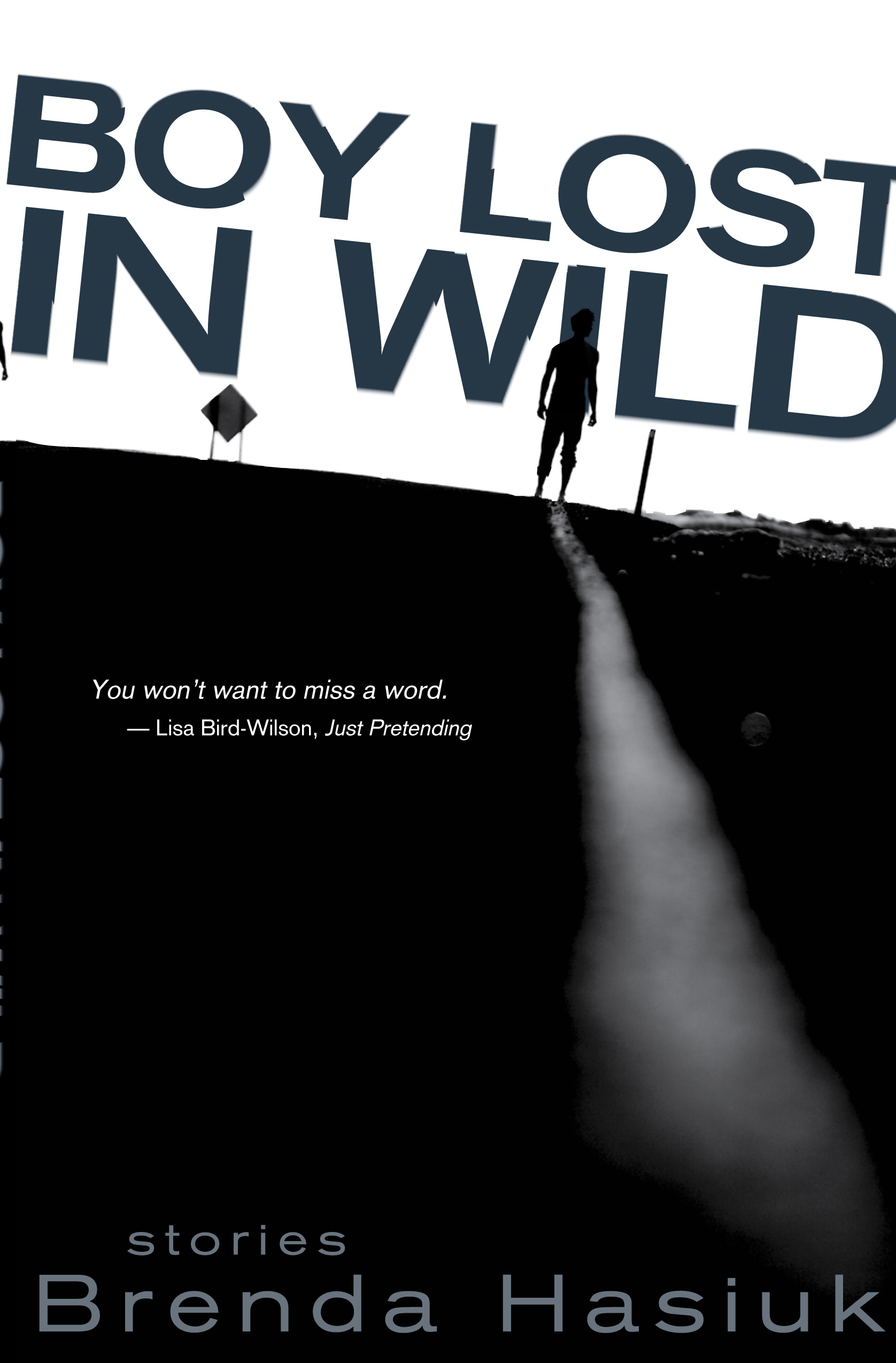

Acclaimed Winnipeg writer Brenda Hasiuk used her hometown as a setting in last year’s Your Constant Star, which follows three Winnipeg teens as they enter adulthood. Boy Lost in Wild, published last fall, is Hasiuk’s first short story collection, and takes place in Manitoba. Some of the stories in the collection have previously been published in the Malahat Review, and the anthologies Up All Night and Kobzar’s Children: A Century of Untold Ukrainian Stories.

A wide array of cultures inhabit the stories in this collection, fitting for an exploration of humanity in our multicultural city. Like in Your Constant Star, many of the stories in Boy Lost in Wild examine cultural differences between characters.

In “Little Emperor,” a Chinese international student is at odds with Western customs in his downtown apartment while recovering from a brutal attack. In “Back Lane Lullaby,” a Ukrainian-Canadian family’s everyday existence is interrupted when a man from Ukraine claiming to be their relative shows up on their doorstep. “Sandwich Artists” chronicles an unlikely friendship between an ignorant young man and his new Iranian-Canadian co-worker.

Each story begins with a set of facts about different cultures and history, including Winnipeg’s. Each set of facts sets the context for the story, and perhaps informs the Winnipeg audience of something they don’t know. For instance, “It’s Me, Tatia” indicates that the Winnipeg General Strike was not generally taught in Canadian schools until the 21st century. In “Blood,” Métis history is provided in a story about a 14-year-old girl who’s just discovered she’s Métis.

The majority of the male and female protagonists in Boy Lost in Wild are teenagers – damaged but hopeful and persevering. First, second, and third person narration is employed throughout.

“Roma Raj,” one of the most engaging stories in this collection, uses a melodramatic voice. In the tale, an Indian father recounts his university transgressions with a woman on campus named “Gypsy Joan” to his young son undergoing medical tests for a lump.

Melodrama manifests in this passage, in which Raj, the father, speaks to his son: “Over the course of our whole marriage I’ve never indulged in such extramarital musings except in dreams, and now, when our only son, our shining star, is in mortal peril, I’m adrift. But you see, Jagat, it’s not that I don’t care. It’s that I can’t seem to shake this thing I must share with you, somehow, somewhere.” The father’s voice is jarring, but his detailing of his short relationship with “Gypsy Joan” is one of the most enjoyable parts of Boy Lost in Wild.

“Little Emperor” is also a notable piece. First-person narrator Xaio, a new international student navigating Winnipeg alone and impaired after a mugging, uses humour to describe his plight. Albert, Xaio’s landlord who refers to him as “Chow,” buys food for him. “The West has failed the visiting international student. So all Albert can do is bring me food I cannot eat. It would be all laughable if it weren’t so painful.”

The sharpest prose in Boy Lost in Wild emerges in “Sandwich Artists.” Casey, who at the beginning of the story, had “accepted that his sex life was a date with a dirty sock and computer screen,” meets his new co-worker Dorri, who is in love with an older guy “in a league all by himself, larger than life rather than popular, leaving her happy to follow alone and admiring and invisible, eating his dust.”

Each story briefly glimpses into Winnipeg lives and their hardships, and Boy Lost in Wild is overall an informative and interesting read.