Andrew Vineberg

A war is raging in a strange and backward part of the world. An occupying army is using advanced military technology and weaponry against a terrified population, drawing the eyes of human rights observers and critics across the globe. I’m speaking, of course, about the American Midwest.

Violence in the Midwest exploded again recently in the settlement of Ferguson, Missouri, a region with a history of apartheid and sectarian division. The chaos has drawn the world’s attention once again to the tragic and seemingly intractable conflict in this historically troubled region.

Tensions flared after the shooting of an unarmed 18-year-old African American man by a white police officer on Aug. 9. The victim, Michael Brown, was stopped by Officer Darren Wilson for jaywalking.

Such check stops are a routine part of any war zone, but high stakes nonetheless. Although Wilson was unaware of this at the time, a cigarillo theft at a convenience store earlier that evening had no doubt produced a general atmosphere of tension and fear in the town, which made violence inevitable.

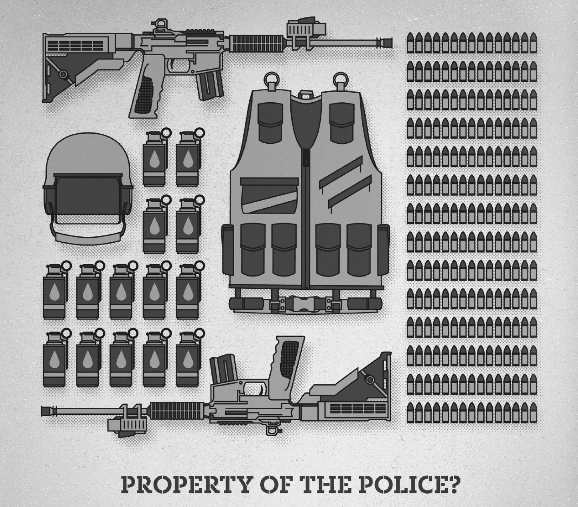

Following the revelation of the killing, as well as further revelations that Brown was shot “more than just a couple” of times (to use the police chief’s words), Ferguson saw the surge of protest and unrest that typically follows the uncovering of such civilian casualties of war. The town’s police enacted a swift military response, deploying their officers as soldiers in green camouflage, wearing body armour and gas masks, and carrying assault rifles and shields. Ferguson soon had all the hallmarks of a classic U.S. military war zone: armoured cars, snipers, tear gas, auditory weapons, and other commonplace tools of control during a military occupation, like a curfew, a media blackout, and a no-fly zone.

Police officers have been pointing their weapons indiscriminately at unarmed civilians and challenging bystanders: “Bring it, you fucking animals, bring it.” Much like in Iraq, journalists in Ferguson must now avoid being shot or taken prisoner.

As usual, there has been no formal declaration of war. The government states as always that this is not a war but “police action.”

And as is typical of American conflicts, international criticism and scrutiny have followed.

Amnesty International has sent in human rights personnel to monitor the crisis. The police force’s actions have provoked criticism from foreign governments and the United Nations. Observers in Palestine have broadcast their solidarity, offering advice on treating tear gas injuries.

Last week, the governor of Missouri declared a state of emergency and placed the area under the authority of the National Guard.

Securing dominance in the strategically important and energy-rich region of the Midwest has always been a priority for the U.S., but since 9/11 America has seen a marked increase in direct military response by authorities every time a new conflict springs up.

Following America’s declaration of war on both terror and drugs, a huge influx of surplus military weaponry has fallen into the hands of American law enforcement. These armaments are acquired for the necessity of stopping terrorism – a responsibility which has always been a top priority for local American police departments.

There are questions about whether these weapons and tactics are being used strictly for the purpose of fighting terrorism. In war, definitions are often subjective. Might these alleged “terrorists” being fought by police also be called “freedom fighters,” “petty criminals,” “minor offenders,” or “innocent civilians?”

This conflict has many names and many fronts, from the War on Drugs to the War on Terror. Ultimately, every front is part of the broader war that is America’s law enforcement—a war waged between the paramilitary forces of the cities and towns of the United States, and the residents of those cities and towns—or at least certain classes of residents, like those in African American communities which stubbornly insist on not reflecting the ethnic makeup of their local police department. For impacted civilians, life is an enduring siege.

Statistics about civilian casualties are uncertain; there is no tally of how many Americans are killed by police each year. A conservative estimate by the FBI of certain types of “justifiable police homicides” records an average of about 400 a year.

More complete estimates report around 5,000 Americans killed in this war since 9/11. Law enforcement claims a black man’s life in America every 28 hours. Local militaries have increased their number of SWAT team raids 1,500 per cent over the last 20 years; most are for drug-related search warrants which are disproportionately carried out against people of colour, and have increasingly resulted in non-suspect casualties.

The war has produced the world’s highest incarceration rate: 2.2 million people.

As with many of America’s wars, Canada has been eager to join the coalition.

Canada’s war against Canadians is nothing new; in particular, the centuries-old fight against First Nations peoples has shifted from royal armies to the police, from the Great Plains to the city streets and prisons.

The North-West Mounted Police, founded as a paramilitary to quell native resistance, was succeeded by the RCMP, who proudly continue those practices. Provincial and city police carry on the Indian wars, whether it’s tactical strikes against unarmed native men, or a war of attrition in the form of procedural indifference over Aboriginal deaths.

In British Columbia, one of the war’s bloodiest fronts, police have killed 267 people in the last 15 years, and ceasefire prospects are grim.

Several recent high-profile skirmishes have brought Canada’s police war back into the public eye, from shooting a schizophrenic cartoonist crawling on the street to their decisive nine-bullet victory over a teenage boy with a knife on an empty streetcar. The shooting of an unarmed man at a baseball game in the Norway House reserve in northern Manitoba served as a stark reminder that war can rear its head anywhere.

Like America, Canada has begun the transition of its “police action” into a war of aggression, and their law enforcement agencies into elite militaries.

During the 2012 G20 protests, Toronto police encircled and contained their civilian opponents with expert military maneuvering. Armoured assault vehicles have been acquired by Ottawa, York, Quebec City, Montreal, and even New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, population 9,500.

This year, Montreal police purchased not just tanks but also long-range sound cannons in the wake of their clashes with hordes of dangerous young people in 2012. And, of course, the RCMP has been proudly returning to their military-colonial roots, not just accumulating multiple armoured vehicles, but sending in heavily-armed squads of Mountie soldiers to ambush peaceful anti-fracking protests in New Brunswick, brandishing Tasers and firing rubber bullets.

There is no question: Canada and the U.S. are embroiled in yet another long, ill-defined, asymmetrical war of occupation in a perilous region full of deep ethnocultural tensions and intractable centuries-old conflicts. A war against the embattled and anguished peoples of North America.

The question is: Might their military involvement be doing anything to prolong the conflict, as opposed to ending it? Certainly crime and unrest in this part of the world are of grave concern. Equally concerning is the creeping rise of volatile radicalism, as indicated by these latest outbreaks of protest. These currents of dissent and insurrection stand opposed to cherished American and Canadian values, like eternal trust in the moral legitimacy of our law enforcement system.

But is military action the proper response to these issues, or simply escalating the violence and frustration in these beleaguered lands?

Furthermore, is there perhaps some larger historical context that links the frustrations of poor Americans back to actions of the U.S. government? Could the economy of the U.S., in some, complicated, hard-to-fathom way, have negatively impacted the financial stability of people all the way in Missouri?

Has the U.S. ever done anything to lose their trust, to draw their rancour? What could possibly motivate them to brazenly take to the streets and demand that officers stop shooting unarmed members of their community?

When citizens take valuable water and milk from an innocent McDonald’s to treat their tear-gassed eyes, is it simple immorality? Or are the police somehow contributing to their actions? These questions are perhaps best left to the sociologists.

The most pressing question of all is, are we simply to resign ourselves to the inevitability of this war? Shall we not ask ourselves if America and Canada might withdraw their forces, scale back their militarism and seek peaceful negotiation with their bruised and scarred civilian populations?

Maybe this is the moment we finally shake off the chains of inevitability and say we will not accept any more of this war.

Waht makes you think its only in America? Ever hear of Robert Dziekanski? It is and has been in Canada for years