Kevin Linklater, staff

Following the global financial crisis of 2008-09, the Canadian economy was held up as a model in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Canada escaped the worst of the crisis; the banks were strong and the housing market continued to grow in strides.

Four years on, however, the overall performance of the economy leaves much to be desired. GDP growth remains anemic; unemployment remains a problem in many parts of the country. Interest rates are at historic lows, yet the Bank of Canada (BoC) is more worried about deflation than inflation. Current policy is not satisfactorily addressing Canada’s economic shortcomings.

The crisis, the policy response, and its failings

Being a small, open economy, Canada eventually felt the effects of the global financial crisis. The government responded with fiscal stimulus, and the BoC slashed interest rates to historic lows in order to stimulate the economy.

The fiscal stimulus has long since gone, as the government moved to tackle budget deficits, but those low interest rates remain, as growth remains weak.

Interest rates are at historic lows and have remained so for years. The availability of cheap credit has failed to adequately spur economic growth and unemployment is still too high.

Furthermore, inflation has consistently been underperforming, registering at the lower end of the desired range. There is very little room for the BoC to further lower rates, and thus very little room to address these deflationary concerns.

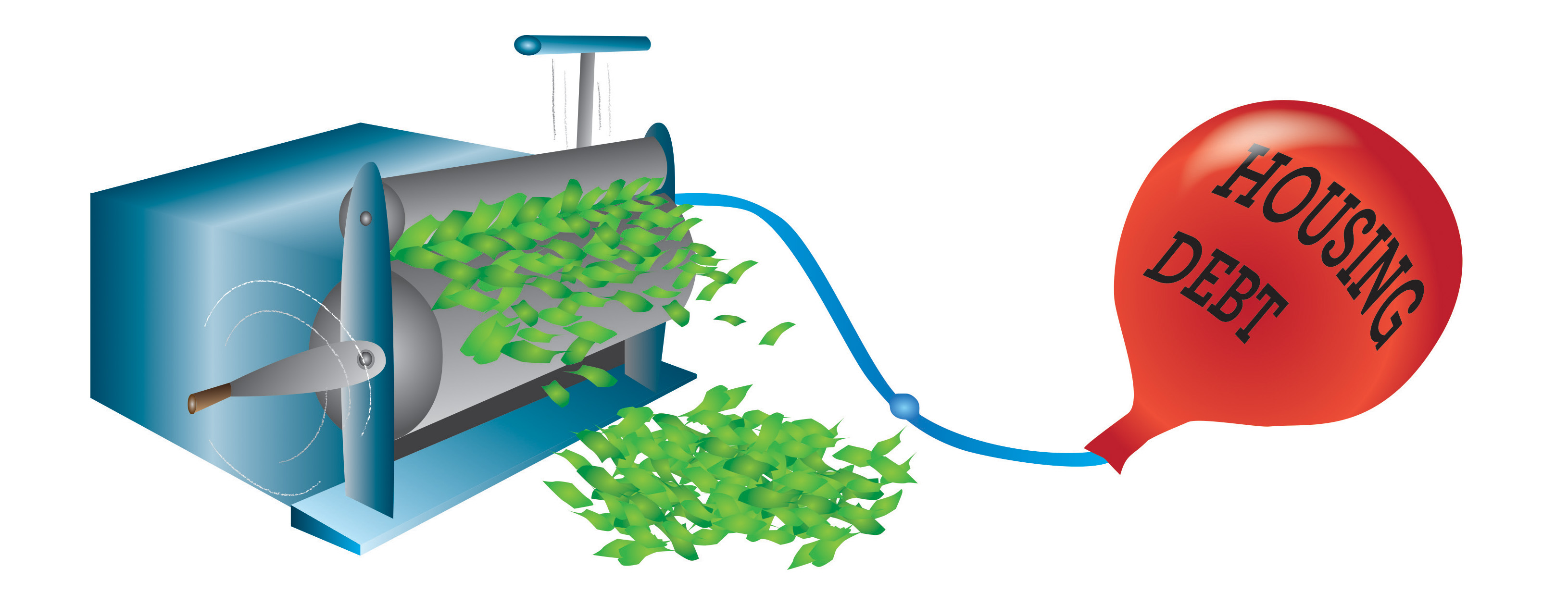

Relying so heavily on the availability of cheap credit has also produced problems of its own: record levels of consumer debt and an overheated housing market.

With easy access to credit, Canadians are living beyond their means. A recent study by TransUnion, a credit rating agency, found that non-mortgage debt is predicted to increase to an all-time high of $28,853 per average Canadian, up four per cent from 2013 levels and up over 40 per cent from 2007 levels.

The housing market is also an area of growing concern. The government has been wary of the possibility that a housing bubble is forming in the real estate market and has taken several steps over the years to tighten borrowing requirements for mortgages.

Despite the stop-gap measures introduced by the government to slow borrowing and cool the housing market, mortgage debt has continued to rise, along with non-mortgage debt – such as lines of credit and credit card debt. Canadians are now carrying record levels of debt.

It is true that delinquency and foreclosure rates remain low, and this is a good sign. But how long will that last? With job creation sputtering and the country’s resource boom tapering off, these increases in debt loads can only continue for so long.

Canada is now dependent on cheap credit to grow the economy, and any rise in interest rates risks choking off growth. This means that there is no room to raise interest rates to check the rise of indebtedness of Canadian households.

The danger is that if and when these historically unique credit conditions change, the positive growth seen in housing and consumer spending will quickly vanish. This is not a good position to be in.

Policy makers need to be putting in place the conditions for continued strong growth in housing and consumption, without the crutch of cheap credit to sustain them.

Possible solutions

So how would this change come about?

What I propose is higher wage growth. This would stimulate economic growth and have an inflationary effect, something that is desirable at this time.

Higher wage growth would have the same stimulative effect as low interest rates, but without the problem of rising indebtedness. Additionally, stronger wage gains would allow room for the BoC to raise interest rates to address the growing debt issue without strangling consumption and growth.

So, how do we achieve stronger wage growth? I see two possibilities: another round of fiscal stimulus that tightens up the labour market and thus drives up wages, or encouraging the unionization of workplaces, which would increase wages.

There are downsides to each of these options; although Canada’s debt-to-GDP ratio is relatively low and there is room to enact fiscal stimulus, the government is currently in a deficit, and a new round of fiscal stimulus may not be politically possible. On the union side, this could scare away capital and discourage hiring if businesses see militant unions rattling their sabres.

However, there are good reasons to believe the pro-union scenario would not backfire for the following reason: though Canadian businesses are sitting on record profits, they are not hiring because they see insufficient demand for their products. Higher wages would increase demand from consumers and send a positive signal to businesses to hire more workers.

The problems facing the economy are not being adequately addressed by current policies, and are having unintended consequences in the form of rising indebtedness. Strong wage growth would go a long way toward addressing these problems, and higher rates of unionization are a way to achieve it.