For the first time ever, ocean explorers have captured footage of a giant squid in its natural environment deep in the ocean. The expedition took place off of Japan’s Ogasawara archipelago, and was funded by the Discovery Channel and the Japanese broadcaster NHK. The footage was taken in July 2012, but has not been discussed publicly until now to coincide with the release of the two channels’ documentaries.

Tsunemi Kubodera, a zoologist at Japan’s National Museum of Nature and Science and one of the crew members in the submersible that captured the footage, has been involved in two previous expeditions of this sort. Those expeditions took still photos of a squid in the deep and video of one at the surface. On this most recent expedition, Kubodera and pilot Jim Harris encountered a giant squid face-to-face in their Triton submersible at a depth of 640 metres.

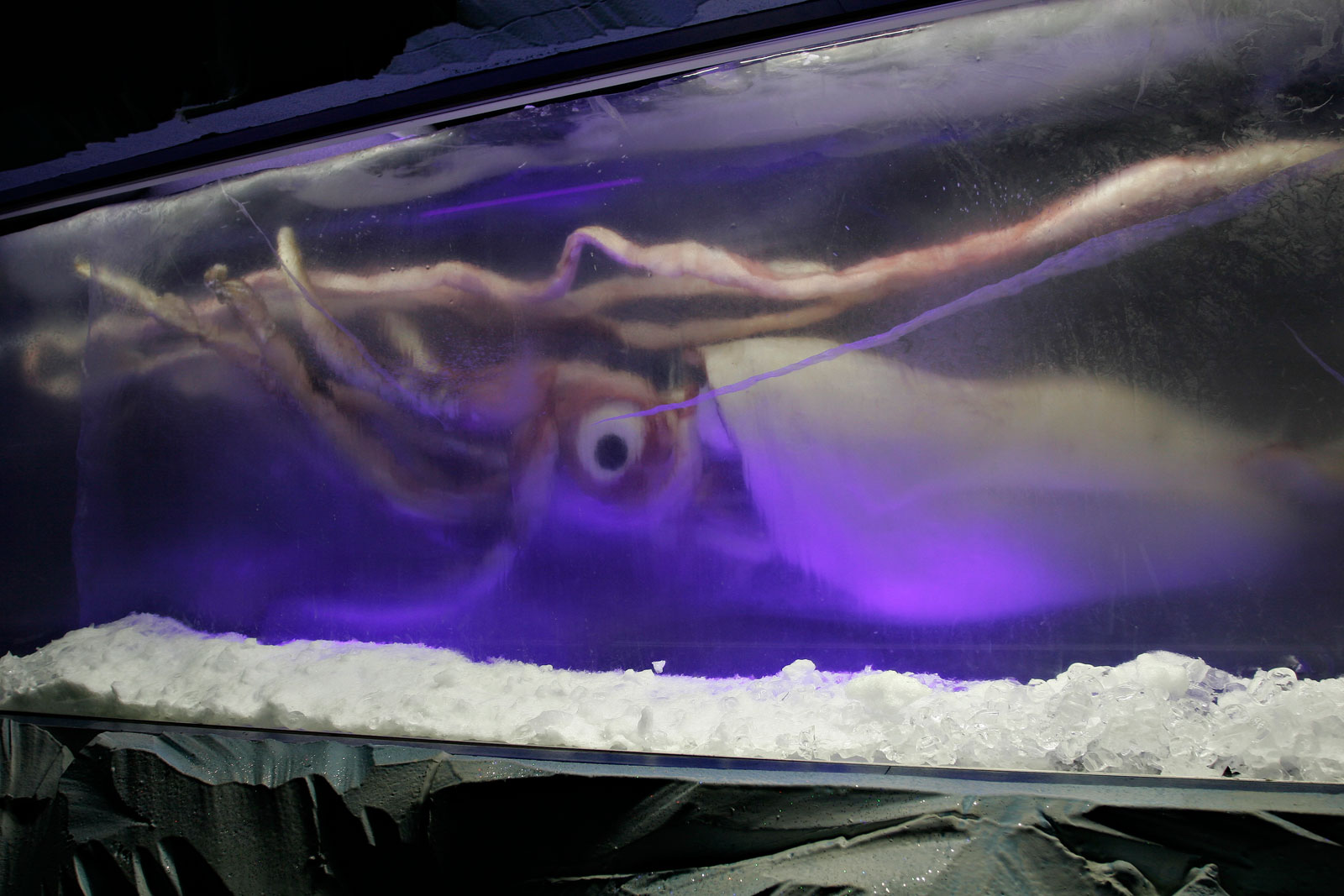

They took low-light footage to avoid scaring it off (giant squids have the largest eyes of any animal, and they are very sensitive to light) but when the crew turned on the sub’s main lights, the squid did not swim away. Instead it stayed for 18 minutes and fed on bait that had been tied to the sub’s side while Kubodera and Harris watched.

“It was so beautiful that I have no words to explain it,” Kubodera said.

Though the giant squid is a massive animal often measuring several metres in length, it is elusive. Living at depths between 300 and 1,000 metres beneath the sea’s surface, the giant squid is hard to find and much of what we know about the species comes from dead specimens that have been found on beaches or accidentally caught in fishing gear. These specimens, many of which are housed in museums, provide enough evidence for scientists to draw conclusions about their life history.

“There are certainly some basic questions that squid experts have yet to answer, such as how old they live, or even how many species of giant squid there might be,” says Randy Mooi, the zoology curator for the Manitoba Museum and an adjunct in the University of Manitoba’s department of biological sciences.

Since the squid is so difficult to find, and many specimens have been found incomplete or mangled, eight genera and many species of giant squid have been identified and named, with varying levels of validity. This new discovery is exciting for squid researchers, who now have a video recording of a giant squid in action.

“This kind of footage, although brief, can provide information on how giant squids move and how they capture prey,” Mooi told the Manitoban.

Clyde Roper, a giant squid expert at the Smithsonian Institution, said that the footage shows that the giant squid, previously thought to be passive, is actually a strong swimmer and a ruthless predator.

The Manitoba Museum is currently showing an exhibit, Marvellous Molluscs: The World is Their Oyster, that includes information on squid biology.

“Manitoba has a connection to giant squids that is much closer than you might expect,” said Mooi, who co-curated the exhibit.

Ninety million years ago, tropical seas covered much of Manitoba, and giant squid actually used to live here. A fossil of the “pen,” or chitinous internal skeleton, of a giant squid is on display.

PHOTO: Fir0002 Flagstaffotos

Nice article!