Ecotoxicologists investigate how toxic substances, such as pesticides and industrial chemicals, impact ecosystems. Their work integrates ecology, which studies the interactions between organisms and their environment, with toxicology, which focuses on the harmful effects of contaminants. Ecotoxicologists are essential in safeguarding the environment, human health and biodiversity.

Mark Hanson is a professor of environment and geography in the U of M’s Clayton H. Riddell faculty of environment, earth and resources.

“I’ve always been interested in nature and the complexity of it, and how it works, especially aquatic things [such as] ponds, marshes, swamps and lakes,” he said. “I wanted to work in the environment to be outside as much as possible, to know that I was making a contribution to ensuring the natural world was protected.”

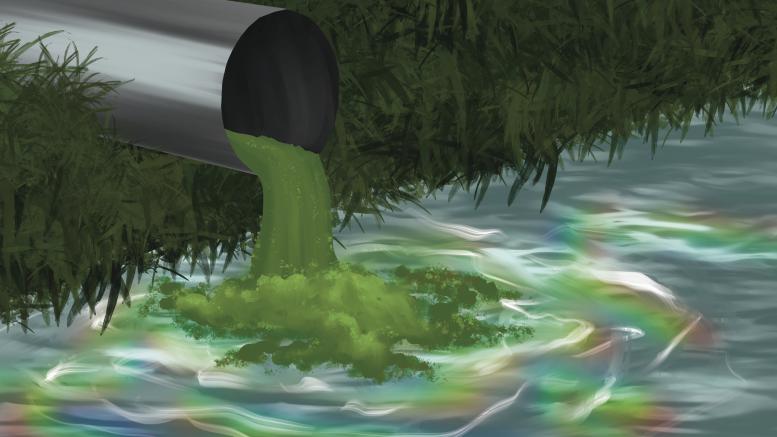

Hanson researches the effects of human-made chemicals, such as pesticides, pharmaceuticals and oil spills, on aquatic ecosystems. His role as an ecotoxicologist involves evaluating the impacts of these pollutants, assessing their severity and duration and determining the potential for ecosystem recovery.

Hanson examines how environmental changes affect ecosystems while estimating risks and generating data on safe chemical levels. His work involves estimating permissible chemical concentrations, developing bioassays and conducting field studies, especially in less-explored regions such as the Arctic.

His research monitors chloride levels in Manitoba’s surface waters, studies the impacts of oil and pharmaceuticals on boreal lakes and analyzes the effects of wastewater in the Arctic. This work helps assess the environmental impact on ecosystems, fish and microbes.

Hanson explained that ecotoxicology developed during a period when the environmental effects of chemicals were largely ignored. Previously, chemicals were produced and released under the assumption that nature would dilute or decompose them.

Persistent chemicals can accumulate to dangerous levels and high initial concentrations can cause immediate effects. In the past, pesticide applications primarily focused on their effectiveness against pests, often neglecting wider ecological consequences. Today, we recognize that these chemicals can also impact non-target organisms, which underscores the importance of thorough environmental risk assessments.

“We need to [ensure] that the surrounding ecosystem, and resources we derive from it [such as] water, leisure, other economic activities, are also all protected,” Hanson explained. “Ecotoxicology helps us do that. Before a chemical, a pesticide gets approved for use in Canada, a whole bunch of ecotoxicology studies need to be conducted, including laboratory tests around different organisms, who’s sensitive at what levels, fate studies in soil, fate studies in water. All sorts of things need to be asked and answered before that chemical now ever gets approved.”

Ecotoxicology prevents environmental damage by ensuring regulatory oversight of chemical use, managed by agencies like the Pest Management Regulatory Agency and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency globally.

Ecotoxicologists aim to balance environmental protection with essential activities such as food production and wastewater treatment, ensuring these processes are sustainable while minimizing ecological harm.

“In this field, you have the ability to […] identify problems and start to potentially solve them,” he said. “Which is rare in a lot of academic disciplines.”

The work of ecotoxicologists is vital for regulations, oversight and environmental protection. Their research directly informs conservation efforts and policy development.

Ecotoxicology stands out because it necessitates a wide-ranging network that extends beyond academia. Professionals in this field must understand government regulations, policies and governance, while also collaborating with industry stakeholders involved in the production and sale of chemicals.

Collaborative problem solving in ecotoxicology is highly effective because it unites producers, regulators and scientists to address environmental impacts. This interdisciplinary approach facilitates real-time solutions and policy changes. Over time, research-driven efforts result in tangible progress, such as the gradual phase-out of harmful chemicals, showcasing the dynamic impact of the field.

“We like the chemical story a lot of times because it’s very simple,” he said. “There’s a company and they’re bad. They produce something. So, if we stop them from doing that, the environment’s protected, while at the same time we’re out there and we’re building new cottages and we’re clear cutting to the lake so we can have a nice sunset view, all these things that ultimately do more damage than a lot of these chemicals would ever do.”

“We’ve got to recognize our individual role in all of these things.”