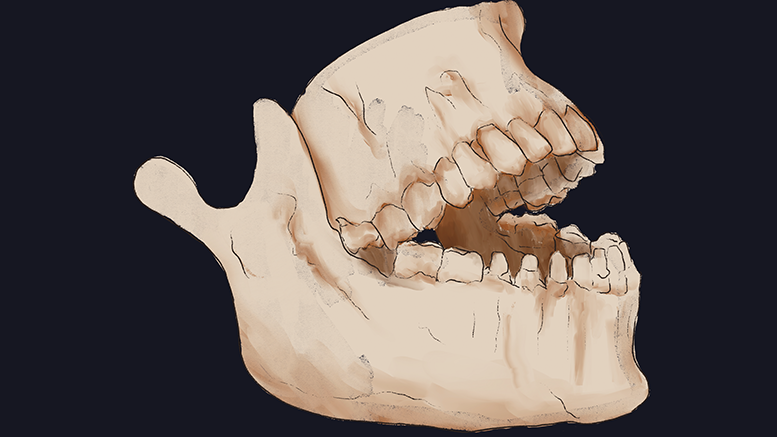

For decades, anthropologists have used teeth to answer questions about the lives and relationships of ancient and modern-day people. Dental anthropology is the study of the development, number, size, wear and pathology of teeth aimed at understanding the evolution and diversity of humans.

Julia Gamble is a dental anthropologist and associate professor in the U of M’s department of anthropology. Her fieldwork has spanned Europe, with experience in Austria, England, Wales, Denmark and Greece.

While Gamble’s work has covered diverse areas of anthropology, she focuses on dental markers of growth and how they relate to indicators of health later in life. She emphasized the breadth of information that can be obtained by examining teeth.

“Looking at past populations, we can kind of look at different segments of their lives by looking at their teeth and looking at their skeletons,” said Gamble. “As an anthropologist, that tells me something about humans.”

Tooth enamel is the hardest tissue in the body. While bone decays easily and absorbs materials from its surrounding, teeth are extremely resistant to changes. Because of this, teeth are often found in archaeological sites.

“We’re living in a period where we’re seeing fairly drastic changes in terms of climate and environment,” said Gamble. “Looking at the past helps us to understand how people adapted and responded to different circumstances.”

Many events that have occurred in human history have continued to shape populations to this day.

One example is the Black Death, a 14th century bubonic plague pandemic that killed up to half the population of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. According to McMaster University researcher Jennifer Klunk, certain gene variants conferred protections against the disease, making those who possessed them up to 40 per cent likely to survive and pass those genes on to future generations.

But while carrying those genes may have helped one’s ancestors survive the Black Death, they have been linked to a heightened risk of certain autoimmune diseases. The same genes that provided an edge to those facing the bubonic plague also predispose them to the inflammatory bowel disease, Crohn’s.

“The developmental origins of health and disease hypothesis is one that we see a lot of study of with modern populations,” Gamble said. “It’s the idea that early life factors and experiences can shape our health experiences later in life.”

She explained that because of the long length of modern lifespans, it can be challenging for a single study to track participants for the entire duration of their lives. Looking at past remains can provide information about the course of a deceased individual’s life.

Gamble expressed plans for her future work to use information gleaned from ancient peoples to provide insight into how current populations are being affected by modern environmental disruptions such as climate change.

“If you can find pollution indicators in their teeth, for example, how is that looking in terms of their current health?” she said. “[My work] has ways to expand into modern populations.”

Gamble encouraged students to take a closer look at anthropology. Nearly every aspect of the human experience ties into anthropology in some capacity. Anthropology, she added, can offer those who study it a greater appreciation of the world.

“It’s an incredibly important field, because it looks at humanity,” Gamble said. “It looks at humanity across time, across cultures and digs into every component of it. And I think in a world where we have very complex variables taking place, a really deep understanding of humanity is important.”