“Did your parents just really like your last name?” is the question I got whenever my second-grade

teacher would call my name for attendance: Gurnoor Gurnoor. “No, I don’t know why it’s like that,” I would always respond. Not knowing why my parents had decided to give me a double name, I would answer every question with this inner annoyance of why my parents set me on a path of answering a billion questions a day about my name.

My mom also had a double name, and I now wonder if her adult education classmates asked her the same questions. Of course, I only wonder this now because back then I was solely concerned with my own question.

“It’s just a last name, it’s just a couple of questions, it’s just… how it is” was the school of thought I followed as I grew increasingly angry and confused as to why I did not have the sense of belonging to a family history. A name that could carry the stories of all who came before me, a name that was clear, and a name I could be proud to hold.

I would ask, “Mom, why do I not have a last name?”

She would dismiss me with, “It’s just complicated and messy, and we just had to.” Eight years later, I found out my mother had lied. It was never complicated, it was just hard to explain to people who were from a different culture. My name is of Sikh origin. It means the light of the guru (the teacher of god’s words). My family, who is not heavily religious, still lived in a place where Sikhism was very present: Punjab, India. For this reason, my name was Sikh without a last name.

An immense number of Sikhs like my family believed that last names prompted discrimination through the caste system. India’s attitude on caste is a slow step forward and just three years ago 30 per cent of the population still saw value in the system. This was the only reason I did not have any last name in India from the ages of zero to six. My parents wanted me to go through life without people associating me to a certain box.

It could have been in a job interview or just the kindergarten annual festivities like a dance performance, but any instance where my name was known, my parents wanted it known as just me. Not the high or low class I belonged to. As much as my parents wanted to show me to the world as Gurnoor, they never intended for me to be Gurnoor Gurnoor.

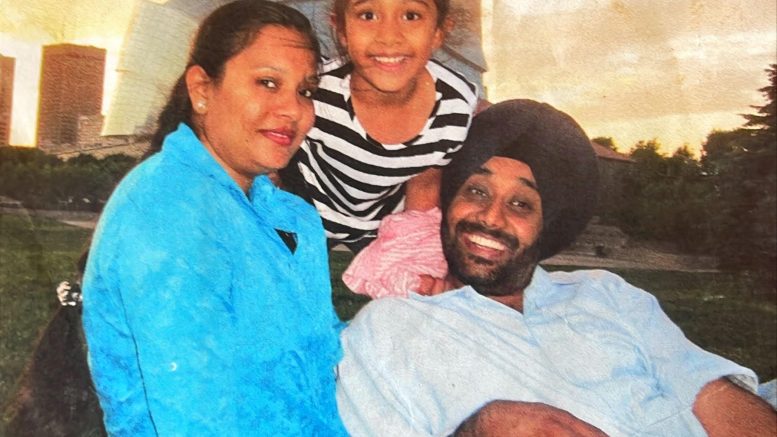

My dad moved to Canada when I was five to explore the world and live somewhere new. My mom and I stayed back in India as our life was pretty settled, but a five-year old can only spend so much time apart from her dad before she is in a puddle of tears crying after hearing her dad’s voice over the phone. So, my mom left her career as a college lecturer and began filling out immigration forms. This is where my name got crazy.

A strange thing about India is that your last name is not as legally important as it is societally, with a grain of salt of course. For identification purposes, your parents’ names can be used, thus making your last name not the only form of name verification.

Canada is a country where last names are of utmost importance, far greater than your first, as I have experienced this firsthand. My mom filled in the name section in the form and left the last name line blank because, legally, I had no last name. My birth certificate didn’t have one. The forms sent to Canadian immigration services were “corrected,” and my name was then doubled for their legal reasons, as I could not be a human in Canada without a last name.

All this stopped bothering me when I realized it was not my parents who set me up. I understood what my mom meant when she said, “We just had to.” They weren’t about to put up a fight with the Canadian government before even getting into the country.

Many years later, after my dad and I had gone to our citizenship ceremony, the next step was to apply for our Canadian passport. This passport was something that symbolizes my citizenship beyond countries, an ideal piece of identification which stated my name as XXX Gurnoor. Yes, my first name had completely vanished because the need for a surname was more important.

I still do not understand why my name was not repeated like in every other document.

“Can… Uhm… One second… X…Gurnoor? Come to the service counter,” said the airport worker.

It was 2022, and I was on my way back to India after seven years when this happened. It was not the poor man’s fault. I mean, who is walking around with XXX on their passport. His hesitation and confusion about my name brought up every memory where my name was either an issue or topic of discussion. People gave me this strange look, and their eyebrows went up, “Seriously, girl, what is wrong with you?” Where was the family I belonged to? Where had my name’s meaning gone? It had become solely a joke. XXX wasn’t a name. It was like an untitled object.

My neighbourhood street in India is close-knit, and when I returned, they all told me how they remembered me and how young I was. I had not seen these people in YEARS, and they could recite the day I was brought home from the hospital.

All these people knew nothing about my name issues. Some only called me by my nickname, not knowing my real name. These people unknowingly made me feel human again by reminiscing about the days of my childhood, the stupid little things I used to do, how I loved certain foods or would get mad at dumb things as kids do.

Telling me that they remembered who I was just because I was once a part of their community. I was reminded that I had grown. I had a life whether I had a last name or XXX as a first because none of these people said anything about my name. The only thing they remembered were the memories they held of me.

My question – why did my parents set me on a path of answering a billion questions about my name – had a simple answer. They wanted people to know me greatly for the memories I once lived through with them, never for the few syllables of a last name.