This fall, two major exhibits opened at the Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG)-Qaumajuq. Though disparate on their surfaces, certain thematic resonances connect them.

The first, titled Tim Gardner: The Full Story, opened in October and is a massive retrospective of a prolific artist with Winnipeg roots. Tim Gardner was born in Iowa City, Iowa before moving with his family to Canada, where he graduated from Winnipeg’s Fort Richmond Collegiate before pursuing a bachelor of fine arts degree at the U of M.

Gardner’s work is largely based in watercolour and depicts friends, strangers and landscapes, highlighting harsh modern aesthetic interruptions to the consuming beauty of North American nature.

The collection spans a number of rooms at the WAG-Qaumajuq and features over 130 paintings and drawings from throughout the artist’s career. These works plainly show Gardner to be a master of his mediums, with the ability to realistically translate his subjects in vivid colour and detail.

The exhibit’s texts reflect this focus on technique, giving space for Gardner to discuss his classical influences and specific technical processes.

What the exhibit seems to lack is a coherent thematic or aesthetic framework.

Despite this being a wide-ranging retrospective on a prolific artist, I found myself confused walking through the loosely organized collection. I was often struck with whiplash in the transitions between kitschy familial works, placid landscapes and recreations of raunchy early digital photographs of his friends.

At its best, the collection displays an unsteady sense of nostalgia and natural connection, a reaction to a constantly changing modern world that still holds space for sublime beauty and humanity.

At its worst, it is a collection of well-rendered but empty renderings of ordinary images.

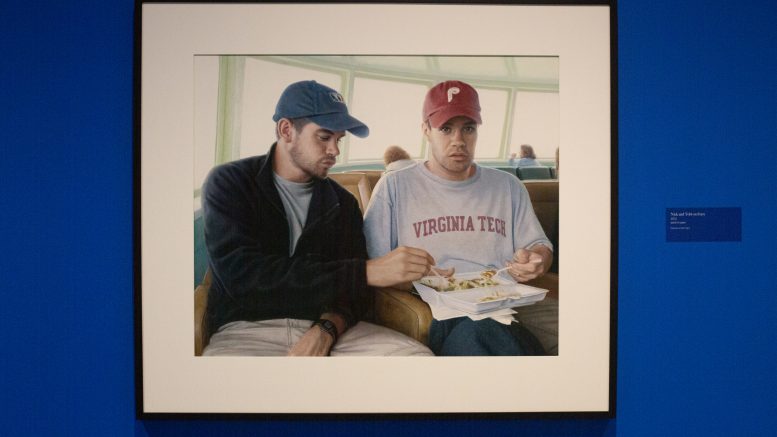

The paintings that struck me most were his early 2000s portraits of friends, which captured masculine scenes of drunken debauchery in all their digitally distorted glory — red eyes and strange colour saturation and all.

There is a certain perverse humour in finding a painting called “Beer Mile” depicting young men in basketball clothes guzzling cans in a parking lot in the esteemed halls of WAG-Qaumajuq.

Later works, like 2022’s “Ribfest” or 2012’s “Fletcher Square” capture more widescreen banalities with emotional assurance, juxtaposing gorgeous natural backdrops with harshly modern idling pickup trucks and strip mall signage, respectively.

These strangely affecting works are muted by their placement among technically impressive but non-descript landscapes, early figure studies and nocturnes that lack the unique aesthetic tension of his other work.

The other, newer exhibit at WAG-Qaumajuq is a much tighter collection that similarly uses landscapes and everyday normalcy to communicate an emotional truth, but perhaps one with a more immediate and clear effect.

Organized by the Ottawa Art Gallery, Dark Ice is a collaboration between artists Leslie Reid and Robert Kautuk that collects photographic prints, videos and paintings to capture the effects of climate change on Northern communities.

The layout of the space is immediately stunning and diverse despite the exhibit’s tight focus.

Prints are laid out in thoughtful order and across a variety of mediums. Some are normal prints, some are printed onto thick sheets of metal and in the second room of the exhibit there are stunning light boxes that bring aquatic photos to life.

On an immediate level, I was struck by the sheer beauty of the images, which capture the landscape of the North in evocative texture and detail.

But beyond these first impressions, the exhibit’s true mark is in its human and political anchoring, communicated both in the work and in supplemental writing and videos telling the stories of local communities affected by changes in the climate.

One cluster of drone photographs by Kautuk shows a wide perspective on researchers and community members working, small figures made a part of the landscape, one with the ice. Another cluster by Reid contrasts Cold War-era aerial photographs of the region with current day images, rendering the changing landscape in literal and aesthetic contrast.

Dark Ice and Tim Gardner: The Full Story are two formidable and varied shows, which, along with the gallery’s permanent collection and its other current exhibitions of Inuit art and Tarralik Duffy’s work, make the gallery well worth a visit.

Tim Gardner: The Full Story opened Oct. 7 and will run until Apr. 7, 2024. Dark Ice opened Nov. 18 and will run until May 26, 2024.