Systemic racism is an issue that plagues many different parts of society, including the health care system.

There is scientific evidence of health inequities that disproportionately negatively affect Black and Indigenous people both in Canada and abroad.

A growing body of research demonstrates that maternal mortality and morbidity rates are higher for Black women globally.

Different studies have reported that Black women in the United States and the United Kingdom are three or four times more likely to die in childbirth than their white counterparts.

We can speculate that Canada would have similar patterns. However, due to Canada’s colour-blind approach to collecting data, it is not certain. Since there is a lack of racial data on Canadian maternal mortality, we cannot identify disparities in our health care system, which in turn can allow for racial inequities to continue unnoticed for longer.

Implicit biases and systemic racism in medicine are among the reasons why Black women have higher rates of maternal mortality. Many Black women, including high-profile celebrities like Serena Williams, report being dismissed and not listened to when discussing their symptoms, concerns or pain with medical professionals.

This could be due to the long-held belief that there are biological differences between Black and white patients, which perpetuates the belief that Black people have a higher pain tolerance.

These beliefs are simply not true.

A 2016 University of Virginia study found that these false beliefs were shared and supported by half of white medical students and residents in a sample. This is extremely worrying because according to the same study, Black Americans are consistently undertreated for pain compared to white Americans.

When looking at research on racial health disparities in Canada, it is evident that Indigenous people have worse health outcomes than other races including higher rates of chronic illnesses and associated risk factors, double the rate of infant mortality, 30 per cent higher post-surgical death rates and an overall lower life expectancy.

These findings can primarily be attributed to systemic racism and racial biases in the public health care sector. This can result in quality health care and services being inaccessible to Indigenous people, particularly in rural areas and reserves.

Additionally, biases that are rooted in racist ideology put the blame for poor health onto Indigenous people without understanding or acknowledging how colonization, socioeconomic factors, generational trauma, racism and cultural oppression play a role in debilitating the health of First Nations communities.

A paper published by University of Manitoba associate professor Brenda L. Gunn briefly discusses the harmful effects of colonialism and its long-lasting repercussions. Examples of this include the spread of deadly new infectious diseases, the illegalizing of spiritual and medical practices and policies such as residential schools that have had generational effects on the well-being and physical health of Indigenous communities.

According to a June 2022 study, First Nations patients frequently experience neglect, disrespect and overt racism when seeking care. This could result in false judgements due to harmful stereotypes made about Indigenous patients by non-Indigenous staff, which can change staff attitudes and the level of care they provide Indigenous patients. This is evident in the countless documented cases of Indigenous people dying of preventable causes.

In 2008 Brian Sinclair, an Indigenous man, was ignored for 34 hours by hospital staff in a Winnipeg emergency waiting room before he died of complications related to a treatable bladder infection because staff thought he was intoxicated or homeless.

Then, in 2015, Keegan Combes of Skwah First Nation was thought to be drunk when he came to a British Columbia hospital for help and did not receive proper treatment until it was too late, which is what ultimately led to his death of accidental poisoning.

In 2020, Joyce Echaquan, a 37-year-old Atikamekw woman, live-streamed her cries for help while hospital staff in Quebec taunted her, saying she “made bad choices” and making other racist remarks before she died of excess fluid in her lungs.

The lack of care and empathy for Indigenous and Black patients from health care providers further reinforces the mistrust that discourages them from seeking medical care. These people died because of racism, a public health emergency that threatens the health and therefore the lives of many Indigenous and Black people.

No one should be practising medicine who is racist. The fact that health care practitioners who hold these beliefs can slip though the wide cracks signifies a systemic and structural failure in the health care system to protect and serve its patients.

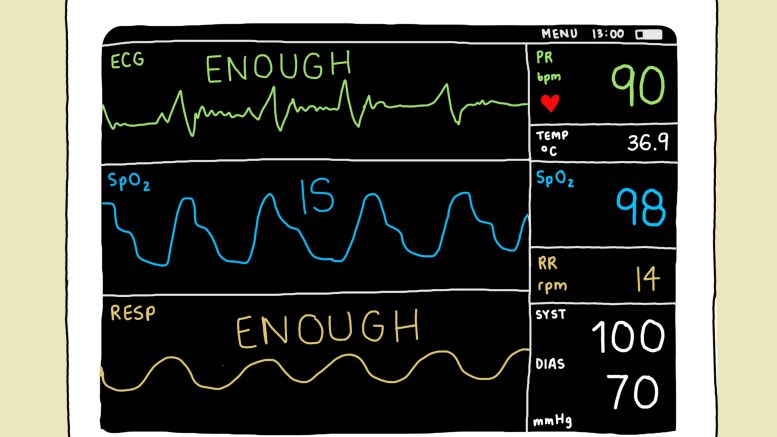

Work should be done to ensure that racial biases are addressed in medical academia and the workplace to guarantee that practising and future health care providers deliver quality care to all. Everyone is deserving of quality patient care that is free from prejudice and discrimination.