Since September, Protests have erupted across Iran and the world following the death of

Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman who was found dead in police custody three

days after being arrested by Tehran morality police for donning an “improper hijab.”

According to eyewitness testimonies, Amini was attacked in a police van shortly after

being arrested. Police claimed that Amini died of a heart attack, and they have denied any

responsibility for her death. Amini’s family, however, have publicly stated that Amini had no

history of health issues.

The suspicious and sinister circumstances surrounding Amini’s death have fuelled

protests in Iran for weeks, with protestors demanding the end of the morality police and the

compulsory hijab. As of Oct. 28, the estimated death toll from these protests has reached

253 people, as Iranians continue the fight for change.

Conversely, in India, protests against a hijab ban in Karnataka state-run educational

institutions date back to January. It’s been reported that 17,000 Muslim schoolgirls in India

skipped exams following the newly implemented rule.

The ban was challenged in India’s supreme court on the basis that it was discriminatory

and violated the right to freedom of expression and religion. The judges in the case reached

a split decision on hijab prohibitions in schools after months of deliberation. This left Muslim

schoolgirls in Karnataka with no real solutions other than choosing between their religious

beliefs and an education.

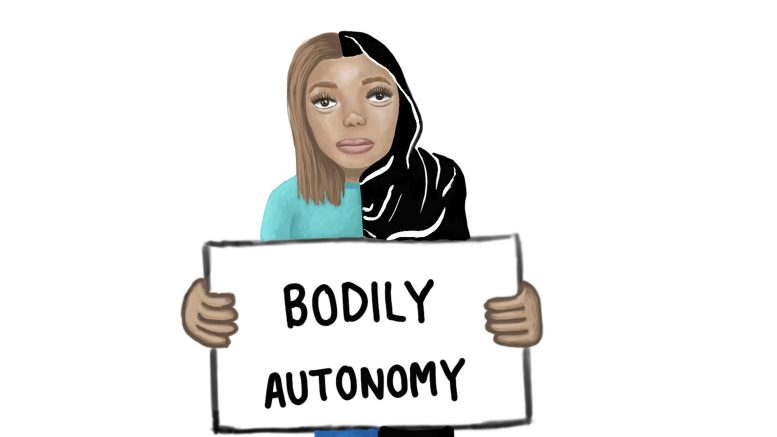

Both incidents, despite their apparent differences, are examples of the policing of women’s

bodies by oppressive and patriarchal governing bodies. In both these cases, women have

been stripped of their right to make a choice regarding their bodies, and have been subject

to severe repercussions when they do not comply with the choice made for them.

I have seen a recurring theme brought up during conversations about each of these

movements. There is a hyper fixation on the hijab controversy alone, as opposed to the

resistance of oppressive policies. This manifests itself into the notion that there is a “right

choice” in debates surrounding the hijab, and that one must pick a side.

It is the idea that you must denounce the hijab completely in order to show your support

for Iranian women in their fight against the compulsory dress code, or that you need to stay

silent about the mandatory veiling in Iran in order to protect and support Muslim schoolgirls

facing hijab bans by preventing further negative publicity for the headscarf.

This is not an issue around the hijab, but around the acute policing that uses the hijab as a

mode to oppress, whether it is compulsory or banned.

Without mentioning the various intersecting oppressions that sparked these protests for

freedom of choice, both movements are reduced to discussions about veiling or unveiling.

These simplistic narratives further promote Islamophobic rhetoric that continues to harm

Muslim communities around the world.

Nevertheless, choosing silence on either of these issues is doing a great disservice to

both of these groups, who equally need our help to gain their freedom to choose.

It is not contradictory to support bodily autonomy for all women.

Whether women wear the hijab or not should be their choice. We should not have to pick

between supporting women in Iran protesting the mandatory hijab or women in India fighting

for their right to wear one. You can choose to support all women in their right to have a

choice.

In doing so, solidarity can be used to further amplify the voices of both Iranian protesters and

Muslim schoolgirls in Karnataka.