University of Manitoba assistant professor Paul Durkin is part of an ongoing project studying the environment in which early ancestors of humans lived. The project focuses on the Ewass Oldupa site in Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania, a well-known archaeological site particularly famous for being the first place where traces of stone tool culture was discovered.

In 1959 and 1960, Homo habilis fossils were discovered at Olduvai, becoming the oldest known member of the Homo genus, to which modern-day humans belong.

Homo habilis, as well as the modern-day Homo sapiens and the more ancient but less closely related Australopithecus genus, is a type of hominin. Previously, this group of humans and immediate ancestors were known as hominids, but that definition has now been expanded to include great apes, like chimpanzees and gorillas and their ancestors.

At Ewass Oldupa, an interdisciplinary team is excavating deposits of stone tools in order to figure out where and how they might have been used as humans began to evolve.

Durkin, a sedimentologist in the Clayton H. Riddell faculty of environment, earth and resources department of geological sciences, is one of the project’s geologists and is tasked with helping identify markers of environmental change and analyzing growth patterns in the soil around tool deposits.

“What [makes] this find unique is it’s kind of sandwiched between volcanic events,” Durkin explained.

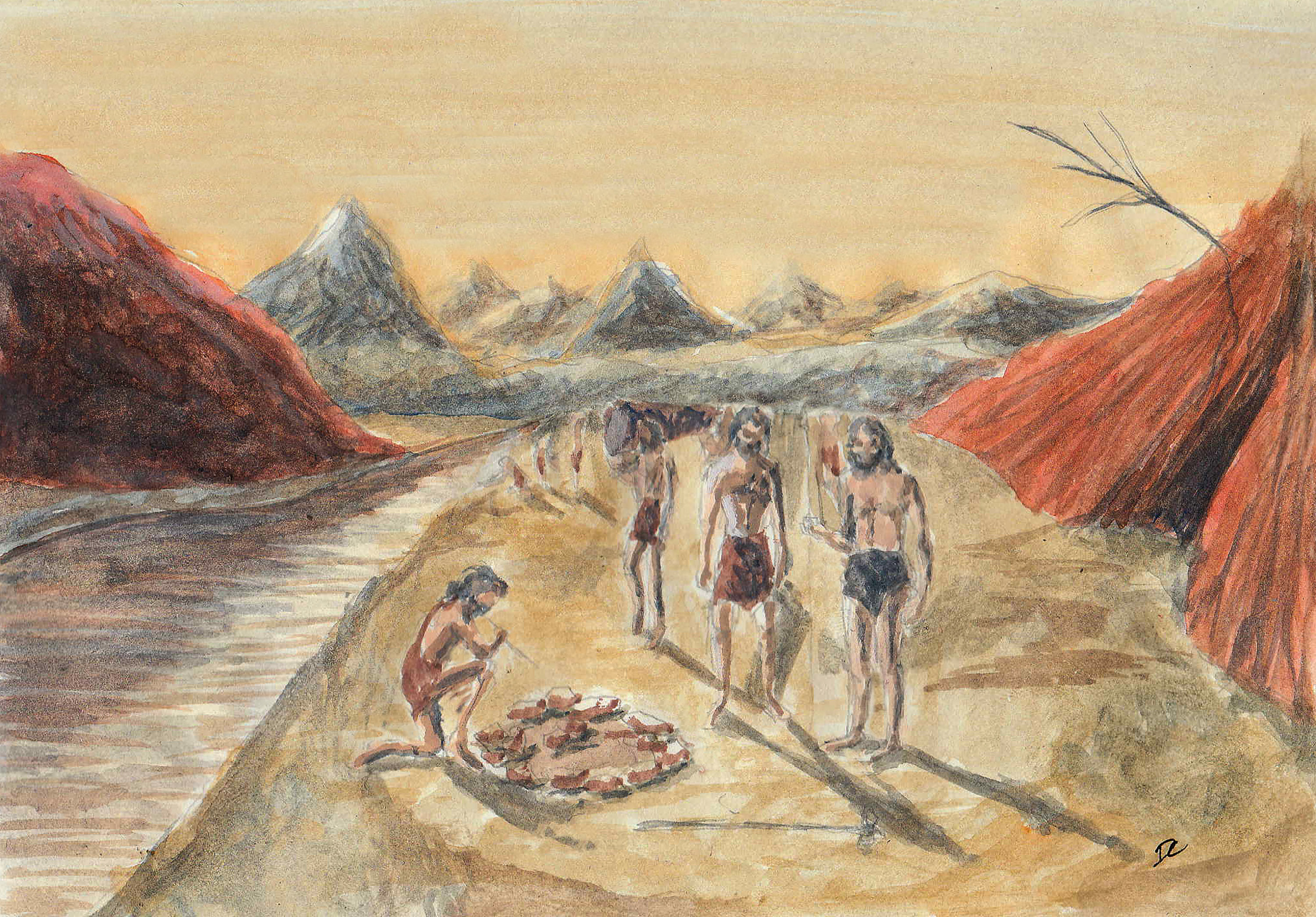

“So, there’s a fairly significant volcanic event below the discovery interval, and we can get an age date on that — and this is something that would have kind of blanketed the whole area with a big mass flow out of a volcano.

“And then we see that the hominins have moved in quite quickly after that, as vegetation started to develop and river systems were developing on this new deposit.

“That’s where we find the earliest record of some of these tools. And then successive smaller volcanic eruptions, that are mostly just ash that have come out of adjacent volcanoes, we can get an age on those, so that provides the bracket for the lower end of the age and then the upper end […] We have a good idea that it’s about two million years old.”

Durkin was invited to join the project by lead researcher Julio Mercader while doing postdoctoral work at the University of Calgary. He spent time at Ewass Oldupa during the 2018 and 2019 fieldwork seasons, though the COVID-19 pandemic prevented him from travelling last summer.

“There’s still a lot more work to do, other areas to test some of these hypotheses that we’ve identified on this first site,” he said.

“For example, we see that next to riverbed deposits, we tend to find a lot of artifacts. So, can we trace where those deposits might be and find them elsewhere to excavate there as well?”

Geological analysis is often the method used to figure out the age of buried specimens rather than anthropological or biological methods. Durkin said that while this type of work was new to him as a sedimentologist, his involvement is a good example of the variety of researchers studying the area.

Though the project lead is at a Canadian university, Durkin is proud of the effort made to collaborate with local experts and scientists on research that directly affects their home.

“There’s Tanzanian co-authors, and even some of the local Maasai scholars that we’ve been able to help sponsor and get into programs at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania as well,” he said.

“So that’s the other side of it, too — trying to improve our inclusion and not just be strictly Western scientists going over to Africa, the way that maybe things were done in the past.”

The researchers also partnered with local Tanzanian television host and YouTuber Masoud Kipanya to create a video about their work. It has sections in both English and Swahili so both local and international populations can learn more about what the team is doing in Olduvai.

As interdisciplinary research becomes more and more common across the social science and humanities disciplines, Durkin is hopeful that in the future, projects like this one will help lead to discoveries that would previously have been impossible.

“In terms of our approach here, it is unique to have this wide range of different disciplines all combining to resolve this one site,” Durkin said.

“Lots of different approaches to holistically get a good sense of what the environment was like — not just based on geology, not just based on biology, but integrating all of that and working together.”

The YouTube video on the team’s work is available here.