Every Sunday morning growing up, I would walk down my home’s green-carpeted flight of stairs to a kitchen enriched by the smell of dark roast coffee and my mom with the morning’s newspaper in her hands. She would either be reading up on current events or working on a crossword she had started — of which, I was often a useless hand of help. I tended to gravitate toward the comics section myself. Nonetheless, newspapers were a central part of morning routines in my household.

But journalism and newspapers are now facing a crisis of validity with various newspapers across Manitoba and North America closing during the pandemic. Since the onset of COVID-19, newspaper revenues have dropped significantly. Due to this unforeseen crisis, 15 newspapers in Manitoba and southern Ontario were forced to close this spring.

Not to mention print papers are slowly, yet surely, fading away due to the digital revolution. People are increasingly receiving their information about the world through social media. By and large, many people are forgetting the value of publishing houses and newspapers. Various calls to defund publicly subsidized and non-profit news outlets like the CBC exemplify this.

Erin O’Toole, leader of the Conservative Party of Canada (CPC), won significant support within the party after promising to defund the CBC’s federally-funded budget grant. A move that Daniel Bernhard, an advocate for Canadian broadcasting, has called “extreme.” But Canadians cannot afford to lose more news media outlets.

When a discourse of value takes place about news media, the conversation almost always gravitates towards the needs and utility of the contemporary. To many readers, the value of news expires as time passes. If a story no longer holds relevancy, or perhaps bigger news outlets get a hold of an angle that makes a smaller papers’ story less attractive, the value of the article is perceived as diminished.

In this way, journalists are always chasing the next lede — looking for that next hook that can validate the ever-expiring value of “yesterday’s news.”

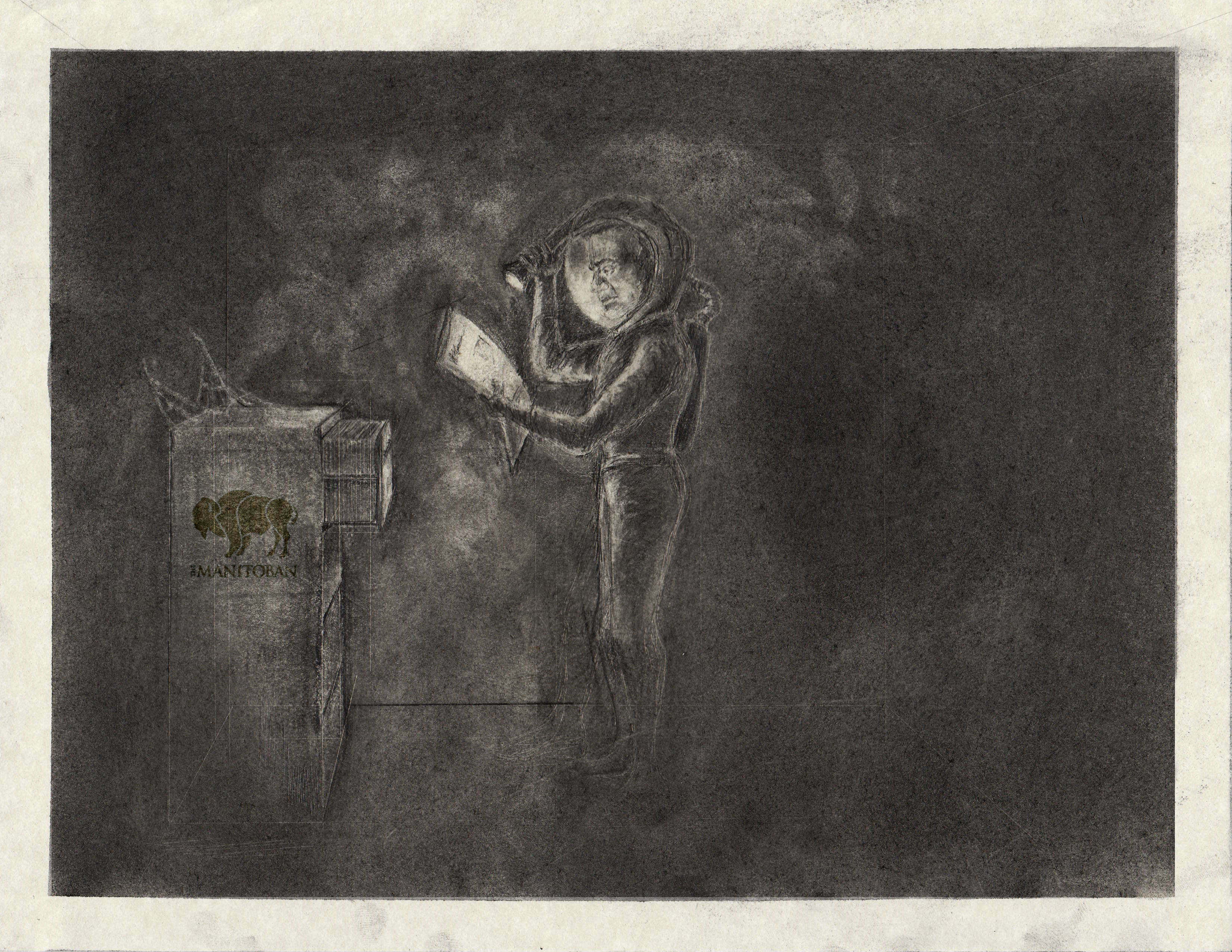

But, this mode of thinking is damaging to the profession. Journalism is just as crucial to future generations as it is to contemporary readers. The value of an article never expires. Instead, it ages like a fine wine, gradually refining itself in a dusty old archive — almost as if it were stuck in time while the world outside was moving in entropic motion, quickly forgetting about it. News articles are snapshots of the past that far outlive us.

Most historians already know this. As one of the Washington Post’s former publishers, Phillip Graham, said emphatically, journalism is “the first rough draft of history.” Stanley Kutler, the historian who managed to get the Richard Nixon tapes from the Watergate scandal released, interpreted journalism in a similar way, calling it “history with a 5:00 p.m. deadline.” And this is not to mention the value that journalists produce for historians.

Today, it’s pretty difficult to find new primary sources not already utilized by another academic. Instead, the field of history has gradually drifted toward redefining theory and new narrative forms. Considering this, it’s fairly certain that, somewhere down the road, a historian will likely look through and use the archived material that, newspapers and other media outlets keep digitally stored.

To historians, journalism acts as a type of recorded oral history that provides glimpses into the consciousness of various historical actors throughout time.

And because of the sheer volume of material being published, this consciousness can be tracked as it changes, thereby giving historians just one of various avenues that can help make the unfamiliarity of the forgotten past more familiar.

Journalists, whether they intend to or not, are continuously leaving behind intricate pieces of themselves and others for future generations to interpret. This makes the profession of journalism indisputably one of several crucial pillars of contemporary storytelling.

Those who wish to devalue the importance of journalism are simultaneously rejecting its kissing cousin, oral history.

Humans’ unprecedented ability to remember the past through arbitrary symbols such as open-ended language is what makes us unique in this world. Written and oral language helps form identity, convey mysticism and narrative and contributes to the very foundation of culture itself.

Journalism does far more than provide value-expiring news for set periods of consumption — it is a medium through which we record and preserve our past. While it is not the only way to record the past, it remains qualitatively invaluable. With this in mind, doubters of the validity and importance of journalism such as O’Toole and the CPC should be careful, they may end up being remembered not just as the antagonists to the art of journalism but to the practice of remembering itself.