The rehabilitation and physical therapy process is difficult for long-term patients. Appointments can number in the hundreds and the cost of care is often steep — not to mention the mental aspect of struggling with repetitive, uninteresting exercises.

The U of M’s Tony Szturm, a professor in the Rady faculty of health sciences’ department of physical therapy, has developed a device to solve those problems. He and his team have created a miniature motion-tracking wireless mouse that provides real-time data to physical therapists while the patient plays video games at home.

The motion mouse is the size of a flash drive, which means that it’s easy to attach to anything from the brim of a hat to a modified game controller, depending on what the physical therapist wants to track. While the patient completes what Szturm calls “game-assisted repetitive task practice,” the motion mouse records how fluid the action is and how long it takes to complete.

Some 500 games have been tested with the motion mouse, and the availability of video games makes rehabilitation more engaging for the patient while also generating a lot of data.

“In three minutes of playing a computer game, they’re going to make hundreds and hundreds of movements,” Szturm said.

“Some fast, some slow, some large amplitude, some small amplitude — the game activities are going to be randomized. I can add precision by decreasing the paddle size, so the beauty of a computer game is that not only are you doing movements, you’re doing precision movements.”

He added that while any game can be adapted as an exercise, different games will be more appropriate to the different skills patients want to restore. Szturm works with many patients looking to improve their fine and gross motor skills, but also patients with cognitive, balance and visual tracking impairments. Some patients may benefit from practicing dexterity and tracking in games like Bejeweled, while others find joystick games like Pac-Man more useful for working on larger arm movements.

“The computer games are actually assessment tools,” Szturm said.

“When you’re doing movements in a computer game, I’m capturing your movements in the context of what they’re supposed to do, and I can come up with all kinds of motor and cognitive outcomes.

“I can see what they’ve done, I can see how well they did it and if they are progressing.”

Szturm recently worked extensively with Sanjay Parmar of the SDM College of Medical Sciences and Hospital in Dharwad, India to trial the motion mouse with 80 children between three and eight years old, but Szturm and Parmar’s work is not the first to link video game technology to telerehabilitation. The Xbox 360’s Kinect — which uses the player’s physical movements in the real world to control their avatar in a game — has been repurposed for remote observation as well. However, Szturm argued that having real-world objects to grip and manipulate is much more useful to the patient’s progress than reacting to the screen.

At $400, the motion mouse’s price is broadly comparable to current major video game consoles, but it’s not available for general sale. Szturm, while adamant that the motion mouse is a medical device, explained that affordability was a driving force in the mouse’s design.

“The therapy has to be effective,” he said.“But the critical issue is — how much would it cost to give them tools that they can take home to do these effective exercises? […] These robotic devices and these sophisticated Kinect programs, they’re 10, 15, 20, 40, 50 thousand dollars. How many people, the average stroke client, are they going to be able to afford that for their home?”

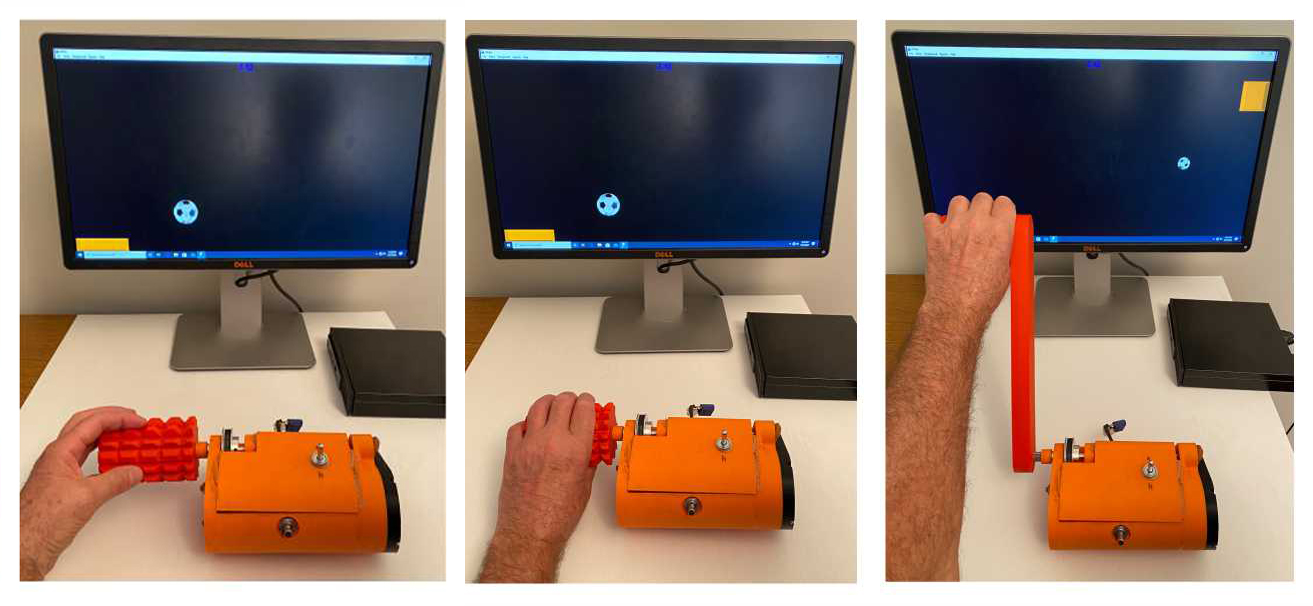

Working with Nariman Sepehri of the U of M’s mechanical engineering department and a team of graduate students, Szturm has also created a manipulandum — an object that is manipulated physically while testing motor skills— that looks like an orange box a little smaller than a box of tissues with prongs for attachments on the top and sides. The team can attach a wide variety of 3D-printed handles specific to the kinds of exercises the patient is doing, as well as adjusting the resistance to the patient’s needs.

The two devices are used separately. The motion mouse collects data on the patient’s movements while attached to something else, while the manipulandum allows the use of a specifically designed object to interact with. Together, the two devices represent a major step forward in at-home care.

The manipulandum will soon enter clinical trials before it is approved for general physical therapy use, with an estimated cost between $500 and $700.