Aristotle became a crucial figure in the Western canon of moral philosophy through his specific and germinal inquiry into the nature of virtue and what it means to lead a good life. He thought virtues were practices conducive to human flourishing, cultivated by reason and habituation, further claiming that to know virtue is simply to behave as the virtuous individual does. The pretence of morality paraded about by our parliamentary officers is more fitting of the later, 20th century German critical theorist Adorno’s conclusion – that to live a good life in modern society is impossible.

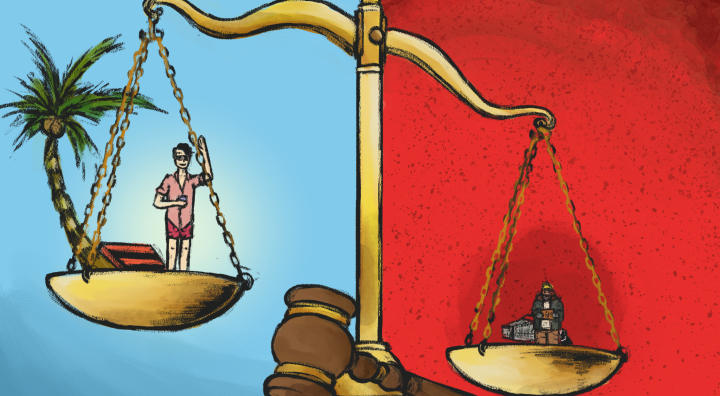

A year-long debate has raged in political circles over whether Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s acceptance of a free vacation to a privately-owned island – extended to him by the Aga Khan, reportedly a Trudeau family friend, multimillionaire spiritual leader of Nizari Ismaili Muslims, and head of two Canadian organizations registered to lobby the federal government – constituted a breach in federal ethics law. For what it is worth, the former ethics commissioner Mary Dawson concluded that Trudeau was guilty of breaching four codes of ethical conduct as laid out in the Conflict of Interest Act, the legislation which guides and gives the office of the ethics commissioner its mandate.

There are two elements of tragicomedy at play here. First is that the ethics commissioner has no real power. As punishment, Trudeau has been chastised as making an “unfortunate” decision that should have been presented to Dawson’s office for consideration. Dawson further stated that the negative publicity surrounding Trudeau’s violation of ethics laws sufficed as punishment for his misdeeds – for a prime minister who is treated by the press as a celebrity in his own right, no less.

Yet second, and more tragically comical, or comedically tragic, is the entire farce upheld by this fanciful office of the ethics commissioner and its so-called ethics law.

The trials and tribulations Trudeau was subjected to are treated as serious formal procedures, as if these parliamentary structures carry legitimate moral weight. Yet distilled down to its essence, the ethical quandary at hand may be put simply: when is it morally inappropriate for one millionaire to accept a vacation to the private island of another millionaire?

Merely framing this question as one worthy of ethical investigation is rank with absurdity. The prime minister – whose office is one of the most powerful institutions in Canada when governing over a parliamentary majority – eloped with wealthy lobbying interests on privately owned land. This is an obscene display of nonchalant opulence in a time when unprecedented economic inequality wracks the livelihoods of people whose informed interests are meant to be dutifully served by the prime minister of a representative democracy.

There is nothing representative of the people of Canada in currying the favour of the rich and powerful, nor in basking in the luxury that power grants. Like former interim leader of the federal Conservative Party Rona Ambrose, who vacationed on a billionaire’s yacht while in a seat of public power, Trudeau’s actions speak to a fundamentally compromised morality. Gorging oneself on cloud nine in previously unimaginable excess, while there are pressing problems of public policy at hand, is a gross violation of the principles of equality that underwrite democracy.

One may protest that Trudeau was on a private vacation, and so the details of his vacation are private and outside the scope of public adjudication. This would be to spout bourgeois apologetics: despite his uniquely sleek and shiny prime ministerial aesthetic, Trudeau is a public servant. In holding the highest public office the state has to offer, Trudeau has consigned himself to four years of answering to the people.

Moreover, the invocation of private affairs here is a confused one, for many citizens formally said to be represented by the prime minister lack the economic status necessary to entertain “private affairs” of the like involved in globe-running vacationing – or to even take a vacation to the nearest campsite. On these grounds, it is perfectly reasonable not only to demand answers and rectification from Trudeau, but also to denigrate the practice of prosperous private vacations from a public official whose mandate it is to seek and materialize the interest of a public whose situation is a poor one.

So long as the public fails to see its interests realized, the private actions of those in public office are worthy of scrutiny and condemnation.

In 2018, 121 First Nations are under boil water advisories. Millions of Canadians are reported to live in poverty. Debt loads are at record levels as contractual job insecurity spreads its corrosive affect across the economy, destroying traditional long-term employment that played a role in bringing prosperity to earlier generations. The security net baby boomers were enmeshed in, a major equalizing factor that contributed to decent quality of life for their generation, is now being shredded by the application of a neoliberal logic of individuation and privatization to governmental social services.

Of course, bourgeois flights of fancy consisting in gluttonous material consumption is the standard decorum of ruling political classes across the globe. Yet the mere existence of this style of political practice – wining and dining diplomacy, if you will – is evidence of its moral corruption, not justification for its continuation. Should we wish to install a proper ethical framework to guide the actions taken by individuals vested with the authority of parliament, we must first render obsolete the disconnect between our state’s peoples and our state’s rulers.

Focusing on the premise of Trudeau’s action instead of the structural makeup of the context which tends toward such action is both a distraction from, and a trivialization of, a system that is unjust in and of itself.

“Parliamentary ethics” under capitalism represent an attempt to legitimate immoral behaviour through installing a formal façade of moralism. Indeed, an office like that of the ethics commissioner is but a crude instrument of legitimation, one which obfuscates the mortal sins of a ruling class awash with a flood of cash while ever-expanding segments of the people they are supposed to serve are starved of the dignity of possessing even basic necessities.

There is no moral authority in an office of these stripes: only a display of the banality of a bourgeois ethics, whose main moral currency trades in the optics of pomp and circumstance. If this office manufactures a moral to be found in Trudeau’s encounter vacation with the Aga Khan, it is that the rich and powerful must be more wary in adhering to an abstract code of ethics that deals not with substantive actions but rather formalities and presentation.

We must reject this bourgeois ethics that would deem acceptable a depraved act on the condition that it is performed in an acceptable fashion. Should we ever achieve virtuous conduct among the ranks of our rulers, it will be in abolishing the unjust system that leads to the basic, problematic, material distinction between ruler and ruled.