According to current research, the Grolier Codex, a Mayan book written approximately 900 years ago and widely considered to be fake until recently, has been proven genuine. This makes the codex the oldest surviving book in the Americas.

The story sounds like something straight from the Indiana Jones movies. In 1966, Mexican collector Josué Saénz received a message – if he flew to a remote area, and didn’t tell anyone about it, he would be shown a myriad of historical treasures. Saénz was flown to what they wanted to be a secret location, but Saénz knew the area and confirmed it to be the Sierra de Chiapas. When there, he was approached by looters, who presented Mayan artifacts to him, claiming to have found them in a dry cave.

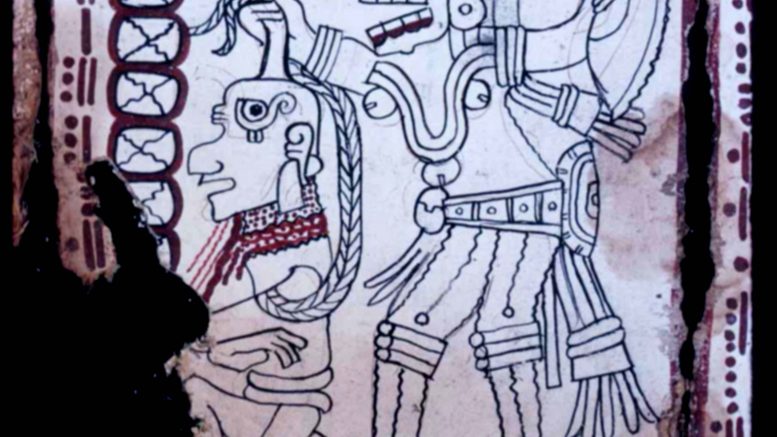

There, he bought what we now call the Grolier Codex: 11 fig bark sheets, all painted on one side, and all extremely damaged by water. The looters allowed him to pursue an expert opinion before buying it, and the expert deemed the codex as fake. Saénz bought the pages anyway.

While this is all an unconfirmed story, it’s the story that archaeologist Michael Coe tells when asked how he got hold of the Grolier Codex (sometimes called the Saénz Codex) in 1971. According to Coe, Saénz allowed him to display the pages at the Grolier club in New York in an exhibition called Ancient Maya Calligraphy after the pages were apparently proven fake. Eventually, the papers were donated to the Mexican government.

The revelation was published in Maya Archaeology, and was lead by a team of researchers, including Coe, who used radio-carbon dating to prove that the codex had indeed existed in the 13th century. Another defining feature was the page’s lack of modern pigments, along with the page’s use of the elusive Mayan blue pigment, a color that scientists have only recently learned the ingredients of.

The pages offer a stunning look into the astronomy studies of ancient civilizations. They use illustrations to track the movement of Venus over a hundred years. It is one of only four codicese today have been able to retrieve, partially because of the fragility of fig bark over time, and partially because conquistadors and priests during the Spanish Conquest of the Americas burned many Mayan books, calling them “falsehoods of the devil.” The other three found their way into Europe in the 16th century, most likely as souvenirs.

Because of the strange nature in which the codex was discovered, questions about its authenticity remain. It is currently locked in a vault at the Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City.