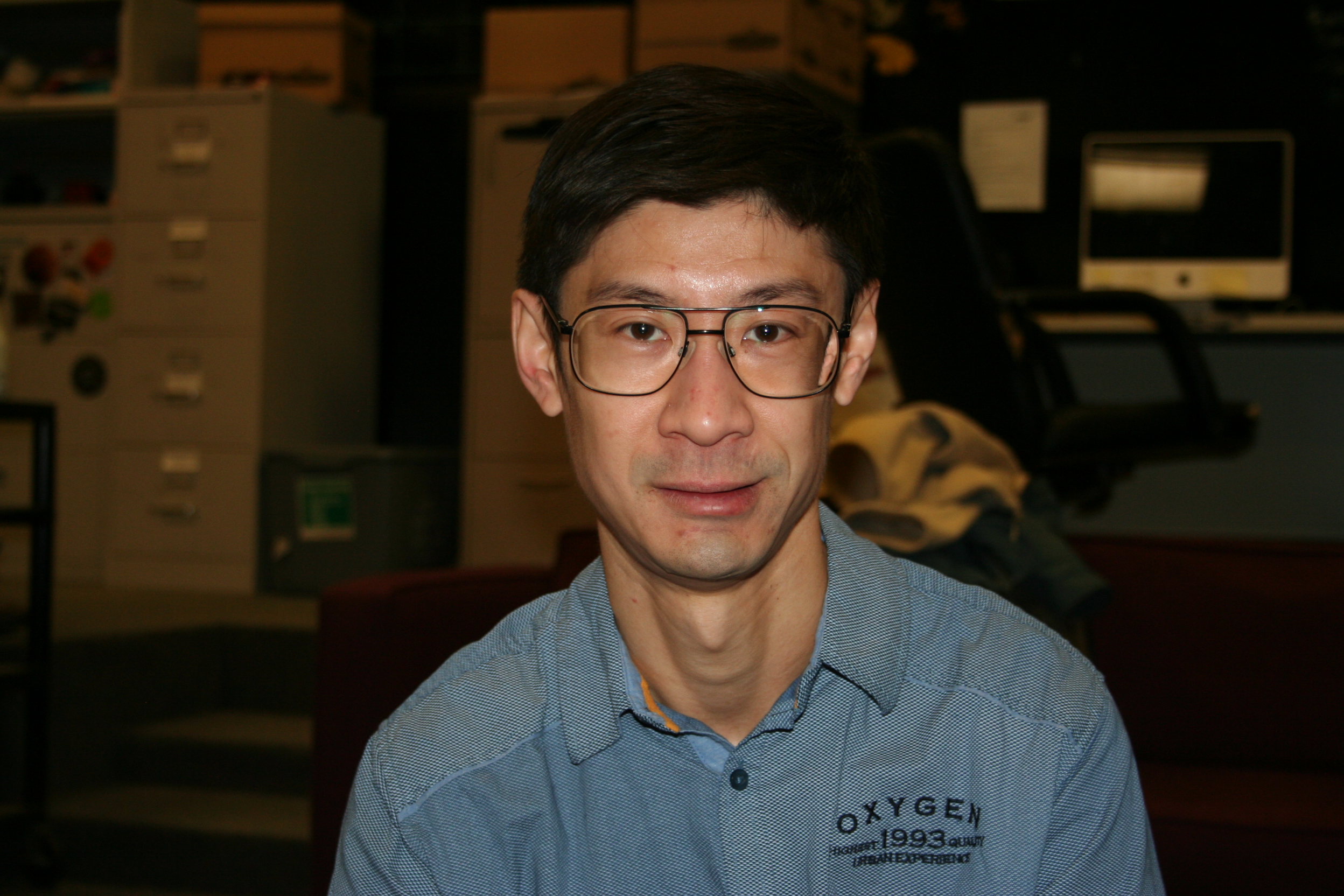

University of Manitoba PhD student Walter Chan first connected with the disability movement in 2002 while completing his master of social work. From there, it wasn’t a far leap to join the psychiatric survivors movement – a movement that advocates for the rights of individuals who are currently accessing or have previously accessed mental health services.

The movement arose in the early 1970s as a branch of the civil rights movement. Major components of this multifaceted movement include rights protection and advocacy, promoting self-determinacy, and creating a sense of pride and culture for people with mental illness.

“Both from a professional viewpoint and a person who’s lived through oppression, I feel this movement is important because a lot of people who go through the mental health system become quite disempowered,” explained Chan.

“If you do get a diagnosis that fits the criteria of the law, your civil rights can be taken away from you with two signatures. And that can’t happen to a lot of other people – it is specific to this group of people.”

Beyond knowing first-hand the disempowerment one feels when receiving treatment in the mental heath field, Chan also felt disempowered as a member of the professional community.

“You felt disempowered even as a professional because you weren’t really given leeway to make many decisions, you were kind of treated as an infant in a way,” he said.

“So from these two directions, I figured this was an important topic for a movement of empowerment and emancipation to spring up from a group who has been marginalized in society.”

Chan noted several other problems within the mental health industry that he experienced as a social worker.

“From a professional viewpoint, even though I was a paid employee, I felt there was a lot of problems in the system and that there was also – for both the patients and the professionals – sort of belittling. For a long time, I really wanted to become a professional and hone my technical skills and be part of the profession. But once I got in the field, I saw that some of the things we were dealing with as workers were not really solvable from our level,” said Chan.

“Getting to the roots of those problems required changing the knowledge base and doing some research, or going into politics. I wasn’t interested in going into politics, at least formally, so I figured it might be better to go into research as a way to solve problems.”

One of the problems noted by Chan was the low morale within the healthcare system, specifically within the mental health subfield.

“Even quite recently, there was a report from Vancouver that found there was widespread harassment and really bad morale within the healthcare system. A large number of staff quit and something like upwards of 50 per cent of people said that the atmosphere was somewhat poisonous,” said Chan.

Chan used his previous work experience at a company in Vancouver as an example of the morale issues the mental health field needs to combat, citing poor leadership as one of the primary sources of this problem.

Beyond issues of morale, Chan also spoke of discriminatory behaviour among the professionals he worked with – something he found incredibly troubling.

“Even though we were supposed to be mental health professionals, there was a lot of stigma around mental illness. Some people didn’t really treat their patients as people – they treated them like illnesses. And you know, those are the people you see everyday, those are the people you are supposed to be helping,” said Chan.

“And because of the mistrust within the unit, I couldn’t really speak about it openly.”

According to Chan, this was the underlying reason for his return to academics. Through his research and his continued involvement with the psychiatric survivors movement, he hopes to help mitigate these concerns from a higher level.

Chan believes that the way to address these issues within the field is multifaceted. Firstly, he hopes to see patients given more control over the treatment they receive, rather than being strictly governed by professionals. Further, Chan feels that people with mental disorders need to be viewed as functioning members of our society.

“Instead of viewing people with mental differences as hopeless or as people who are ‘throwaways,’ it’s better to have an attitude of being hopeful and really recognizing that people with mental differences aren’t that different from you and I,” said Chan.

“I think another important thing to focus on is the social determinants of mental illness. I think the majority of mental distress is caused by oppression in society and if children weren’t being abused, if women were not being abused, if there were not such an emphasis on profit, if people treated people more like human beings, then that would probably decrease a lot of mental distress in society.”

This article was originally published in the Gradzette.