Researchers from the Flinders University of South Australia have developed a simple and cheap substance that may make cleaning up mercury pollution a whole lot easier.

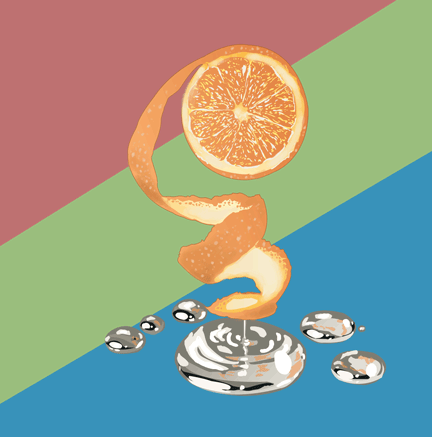

The compound, sulphur-limonene polysulphide, is created by reacting sulphur with limonene, a fatty molecule found in the oils of citrus fruit peels.

Millions of tons of sulphur are produced annually as byproducts of the petroleum industry. Limonene is isolated from discarded citrus rinds.

Because the starting compounds used to produce the polysulphide are mass-produced byproducts, it is inexpensive to synthesize.

The polysulphide is produced by adding limonene in a one-to-one ratio to molten sulphur, which is heated to 170 degrees Celsius. After cooling, the mixture takes on the form of a red, waxy substance. The final product can be manipulated into a variety of shapes, and can even be used to coat other materials.

Sulphur-limonene polysulphide does not dissolve in water, meaning it is an attractive compound for use in cleaning environmental water samples.

The research project started out with the simple goal of developing a new plastic out of readily available industrial by-products. The researchers ultimately thought to test the polysulphide’s ability to sequester mercury since elemental sulphur has been used successfully in mercury disposal.

Sulphur-limonene polysulphide was shown to bind mercury rather effectively. In experiments, the polysulfide successfully absorbed mercury from spiked river water and pond soil samples.

Unexpectedly, the polysulphide changed to a bright yellow colour when it bonded to mercury. This colour change was not observed with any other tested metal.

While other highly effective substances exist for use in removing mercury from the environment, sulphur-limonene polysulphide has the added benefits of being cheap, easy to produce, and has a way to alert users when it has undergone mercury binding via colour change.

To ensure that the polysulfide is safe to use in waterways and ecosystems, the researchers conducted toxicological studies on liver cell lines. They showed that water exposed to sulphur-limonene polysulphide did not pose a negative health effect to the lab-grown cells.

The researchers hope that sulphur-limonene polysulphide will be used to coat the inside of domestic and waste water pipes, as well as in large-scale mercury remediation projects.

Mercury in Grassy Narrows

Sulphur-limonene polysulphide would be an excellent resource for the approximately 1,500 people living in Grassy Narrows First Nation, a small Anishinaabe community about 200 kilometres east of Winnipeg in northwestern Ontario.

Between 1962 and 1970, the Dryden Chemicals pulp mill dumped 9,000 kilograms of mercury into the English-Wabigoon River system. The Grassy Narrows community relied heavily on fishing as their main source of food, but high levels of mercury in fish discouraged this practice in the 1970s.

The individuals living in Grassy Narrows are still experiencing the effects of mercury poisoning today.

Sediment mercury levels in parts of the Wabigoon River are currently twice the threshold for remediation. Recommendations for remediation were proposed and subsequently ignored 30 years ago.

A recent study showed that mercury levels are still rising in the waterways around the community.

Concentrations of mercury in the top sediment layers of the river system indicate that mercury contamination is ongoing – over time contaminants are buried away in the bottom of river systems.

A report conducted by fresh water scientists for the province recommends investigating if commercial logging endeavours in the community are the source of this pollution.