Winnipeg writer David Alexander Robertson’s work has been published in Prairie Fire and CV2. He is the creator of several graphic novels, including the bestselling 7 Generations series; and he contributed to the 2012 anthology Manitowapow: Aboriginal Writings from the Land of Water. He was also recently awarded the John Hirsch Award for Most Promising Manitoba Writer at the Manitoba Book Awards.

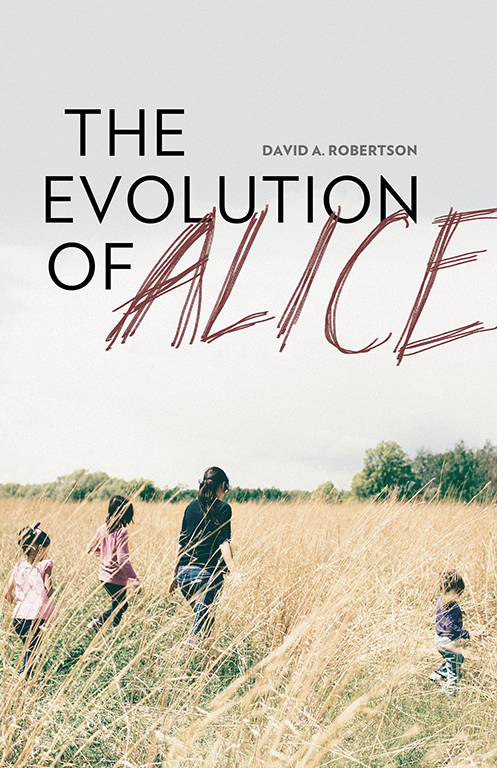

Robertson’s debut novel The Evolution of Alice, published in 2014, follows single mother Alice as she raises her three daughters on the reserve she grew up on. When her family is struck by tragedy, Alice, along with her family and best friend Gideon, must find ways to cope.

Gideon provides first person narration for the bulk of the novel. He is only one of a number of characters who together form a sense of community while trying to find solid ground.

While Alice’s story is central to the plot, these compelling side characters also drive The Evolution of Alice. The reserve’s sense of community in dealing with tragedy is revealed in brief vignettes. Whether it’s grade schooler Matthew, who just found out he is part Cree and tours the reserve; or Alice’s niece Sara, who’s haunted by the deaths of so many of her loved ones; each character is touched by their own or someone else’s tragedy.

Robertson contrasts portrayals of the reserve and the city throughout the novel. Both are tragic, but on the reserve there is a sense of communal healing. In Winnipeg almost everyone is a stranger, wandering and lost.

This distinction is evident in Alice’s experience in the city: “Walks in the city weren’t the same as walks on the rez – that much was clear and unsurprising. It was so loud in the city, deafening really, and her eyes rested not against the vastness of the rez and the quiet of its seclusion, but rather against the concrete and steel of the city, cold and austere.”

Often through a colloquial voice, Robertson pairs first person and third person narration. The first part of the novel is primarily told through Gideon’s humble first person narration. This later switches to third person narration for the last part of Alice’s story.

This colloquial voice is exemplified in Gideon’s introduction: “The only thing you need to know is something you might have already guessed. Alice, she loved her girls more than anything. For Alice, it didn’t really seem like there was too much else to love, so she just threw all her love at them. I’m a friend of hers, me. Name’s Gideon.”

While Gideon telling Alice’s story is emblematic of the sense of community evoked in The Evolution of Alice, the novel is missing Alice’s voice. For this reason, the story is more Gideon’s than Alice’s.

Robertson’s strength lies in his illuminating examination of weighty topics such as racism, discrimination, domestic violence, and suicide. The Evolution of Alice is sad, beautiful, and hopeful.