This was originally going to be a very negative article about the students camping outside of University Centre for 5 Days for the Homeless. I appreciate that they’re raising money for a good cause, but I don’t think dressing up does much for awareness or understanding. But complaining about people dressing up doesn’t do much for awareness or understanding, either.

To help towards the sleepers’ goal—raising awareness of the hardships of homeless youth—I’d like to share what being a young homeless person was to me, based on the time that I’ve spent in that situation: not the experience of someone who’s known a life of suffering, but the experience of a person who’s slept without a home, and done so without encouragement, food brought to him, or, most importantly, the knowledge that he couldn’t be kicked out of the place he was sleeping for the night, for many nights in a row.

This isn’t the experience of mothers, elderly, or disabled who are homeless. I’m young, educated, and healthy – just like the people hanging out on the steps of University Centre. But unlike them, the meaning of being homeless isn’t something I have to concede I couldn’t manage or imagine. What does being homeless mean to me?

Being homeless means not going for walks in the rain, because you don’t have another set of clothes. It means having few or no clean changes of clothes, because you have to carry the anything and everything you have yourself; and vanities are heavy when you carry them on your back. It means not having a place to shower – and even if you don’t care, the people who shower, shampoo, condition, moisturize, blow dry, and towel down every single morning do care, and aren’t very prone to pretending they don’t.

Being homeless means learning to fall asleep observant, wake up on guard, and sleep lightly. If you have something that matters, you fall asleep with your arms around it. You wear your shoes to bed. You also wake up, every single morning, to the rebirth of the sun, to dew, to mist. Or maybe to the realization that the concrete corner that seemed at least a warm shelter last night when all you wanted was somewhere soft reeks of urine, and now you do too, and there’s a police officer telling you to move out.

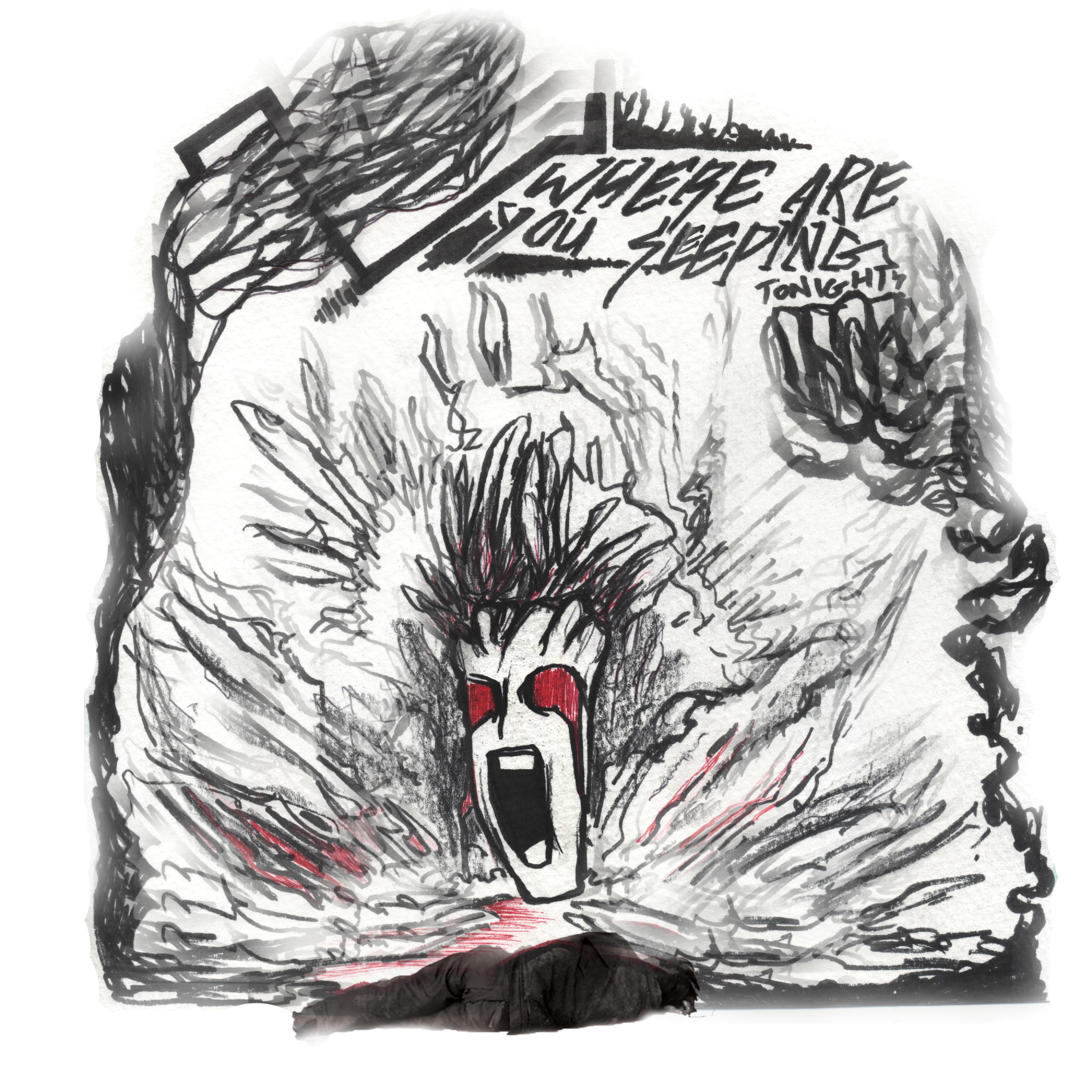

It means not having a place of retreat. No private place to go when sad, alone, scared; nowhere to be angry, or less than couth, without being judged. What was your assumption the last time you saw a homeless person crying, screaming, muttering to themselves – things we all do at some point?

Maybe you were right: maybe they were drunk, or high, or fucked in the head. Either way, they weren’t blind, and in the midst of tears, rage, darkness, they saw you: they knew your assumption, and they had nowhere to shelter from it.

Being homeless means having no money to burn. And realizing how few places you’re allowed to be, to loiter, in our society without spending money, or at least intending to. Our cities are vast, glittering hives of places to spend money, or to enjoy the things that we’ve spent money on. Coffee, food, movies, parking, driving, sitting in your house or yard. Conducting business. By the time you take away all the places you can’t be without spending money, what are you left with? Public parks, and benches. The benches are designed so that you can’t sleep on them, and the parks are patrolled.

Being homeless means being hailed as “brother” by people who’ve never met you, but who know you. It means being generous with your food, your smokes, your alcohol. With anything and everything you have. When you have little, you give a lot.

Being homeless means being generous with your love. It means wanting to be loved. Wanting the chance to express that love. To yearn to create art, but to have no medium. To try to speak, but have no voice that people will listen to. To have your smiles cast to the ground by angry glances, eyes that flash “how dare he.”

It means being alone.

Being alone leads a person to think – about who they are, what they’ve done. About who they’d liked to think they were. Being alone, you’re forced to come to terms with the things you already know: “the person I’ve been isn’t the person I want to be.” With a home, that knowledge leads to growth and, through it, peace. Without a home, it’s a Sisyphean burden that teaches you the priceless value of what you don’t have.