Is “age of technology” an appropriate term to use in this discussion?

It might seem like a silly idea—it’s certainly a digression—to end the “love in the age of technology” feature by questioning whether age of technology is a misnomer. But my hope is that by exploring the significance of the term “age of technology” we might learn more about the impact of technology on love and romantic relationships in our society.

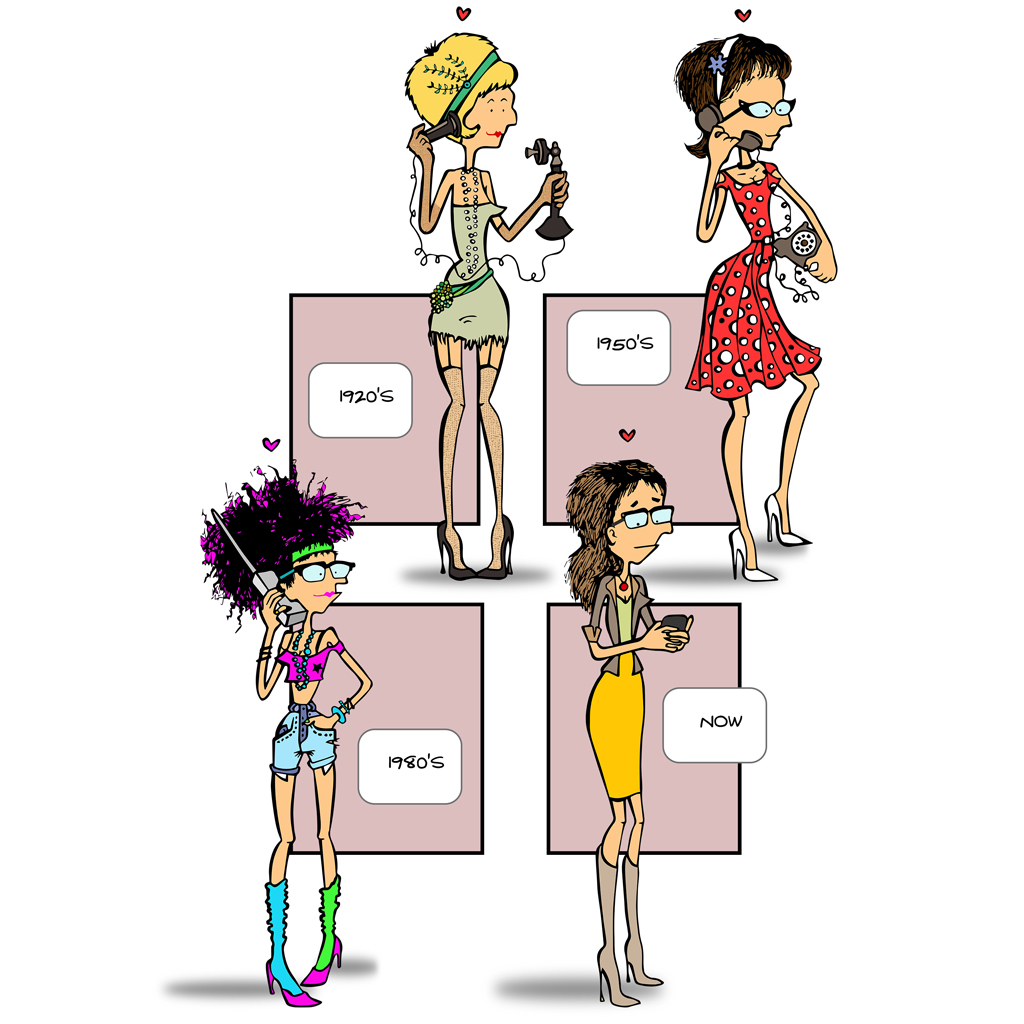

Age of technology brings to mind computers, phones, and the Internet. Love in the age of technology evokes images of people using dating apps and websites and maintaining long distance relationships through video chatting – all of which are phenomena exclusive to the modern age.

Those are generally the images we are referring to in the scope of the feature—images of love in the information age—but the term “age of technology” can have a much broader meaning than what is often associated with it.

Technology is a much more nebulous concept than the way we generally conceive of it. It’s not exclusively computerized or mechanical.

In a journal article titled “Technology and State Government,” published in 1937, American sociologist Read Bain writes that technology includes “all tools, machines, utensils, weapons, instruments, housing, clothing, communicating and transporting devices and the skills by which we produce and use them.”

The use of controlled fire; bow and arrows; simple tools, such as hammers; canoes; igloos; carrier pigeons; nuclear arms; all of them are examples of technology according to Bain’s definition. It’s no wonder we tend to limit our imagination to modern electronics when referring to “technology.” Bain’s definition is very abstract; it’s almost harder to list things that aren’t technology when even the “skills by which we produce and use various [technologies]” are themselves considered technologies.

Bain goes on to argue that “social institutions, [ . . . ] values, morals, manners, wishes, hopes, fears and attitudes are directly and indirectly dependent upon technology and are mediated by it.”

“A technological device cannot be dichotomized into material and non-material culture traits,” he argues.

The potential range of our culture is bound by the technological capacity of our society.

By Bain’s definition of technology, all of human history could be defined as an “age of technology.” In the same way that the Renaissance is often thought of as a period of “culture” while culture is simultaneously a foundational part of any society – from small tribal communities in Papua New Guinea to North America in the Internet era.

This might come across as somewhat obtuse, but it should serve as a reminder that the current influence technology has on how we love is not categorically different to what it was decades, centuries, or even millennia ago – our love and romantic relationships have always been mediated by technology. The difference is one of scale.

We’ve never had greater technological capacity as widely available as it is right now. It has been increasing and becoming more widely available at an impressive rate and that trend is likely to continue.

According to Moore’s Law, a computing term coined in the ’70s, the number of transistors in an affordable computer will double every two years. The more common form of this is to say that processing power will continue to double every two years. Some people, including Gordon Moore, the inventor of Moore’s Law, suggest that this “law” will not hold steady in the long run and that it may be approaching a ceiling but for now the trend remains, at least in principle.

Access to the Internet and modern technologies will continue to become more widely available globally. The majority of the next billion Internet users will be coming from countries identified as “developing countries.”

These new Internet users will be gaining access to the Web through low-end cell phones as that technology becomes increasingly available globally.

Our technological capacity provides us with greater opportunities to connect with one another. It’s best that we remember that, acknowledge these technological changes will have an impact on us and our relationships, and adjust our lives and the broader culture in response.