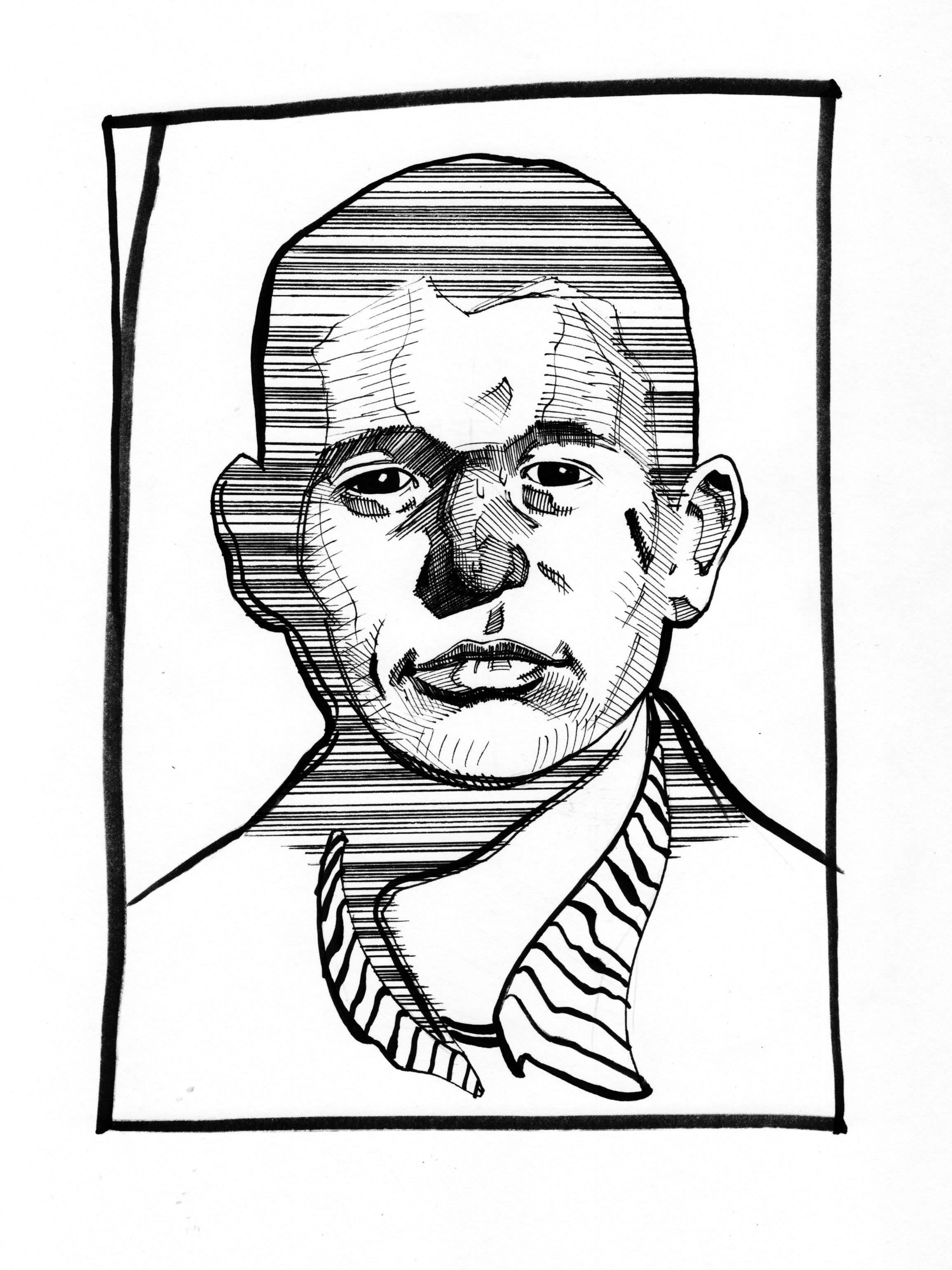

Last Wednesday, indigenous Canadian educator and broadcasting personality Wab Kinew spoke at the University of Manitoba’s Aboriginal Student Centre as part of the native studies department’s 2014 winter colloquium series. Kinew discussed his travels, issues of identity, and what being indigenous means when travelling abroad.

Kinew introduced his presentation, entitled “The 8th Fire and the World: Anishinaabe in Global Context,” with a seemingly straightforward and singular question of personal identity: “who am I?” He proceeded to show that the question necessitates a complicated answer.

“Who am I? Well, I’m an Anishinaabe kid from Northwestern Ontario who works in the United States for an Arab-owned television network. And that’s the reality of the world today [ . . . ] What does it mean to be indigenous when I go to Dubai? What does it mean to be indigenous when you are no longer indigenous to the place where you are?” asked Kinew.

Kinew, who recently took up a position as a foreign correspondent for the Al Jazeera media network, shared a story of a trip to Yemen, and how it put his identity as Anishinaabe into a global context.

“I was sitting with these guys, about to do an interview on the topic of their brother, who had been incarcerated in Guantanamo Bay [detention camp] for close to a decade. We sat there for a while before the interpreter arrived, trying to just hang out, but only being able to stare at each other and nod back and forth awkwardly. And then his face lit up and he pointed at me and he said ‘Cherokee!’ and sat back with a satisfied look on his face.”

Kinew went on to explain that many in Yemen were generally unaware of the history of First Nations people in North America; according to Kinew, it was assumed that people who looked like Europeans had always inhabited the continent.

“This forced me to confront [ . . . ] how do I explain to this person what it means to be Anishinaabe when they have no idea of the existence, much less the details, of the cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas? It was a real eye-opening experience for me.”

Kinew also touched on the importance of preserving indigenous culture and language, even in a modern, capitalist, global context.

“In today’s economy, the most important thing is knowledge. And having a plurality of knowledge and a diversity of viewpoints will make us stronger. That is why it is important to hold onto these things,” said Kinew.

The U of M’s Fort Garry campus will be the site of a multitude of events this term geared towards a First Nations audience. UMSU Aboriginal students’ representative Clyford Sinclair recently hosted a roundtable discussion, aimed at identifying and tackling some of the most pressing problems facing indigenous people in Canada today.

“I was approached by CFS Manitoba to see if we wanted to host a large Aboriginal gathering with the intent of formulating resolutions for change. And there were four main issues identified: missing and murdered women, post-secondary education funding, community organizing, and environmental justice,” Sinclair told the Manitoban.

The issues identified at the discussion will be taken up at a Feb. 14 meeting, where speakers with expertise in each of the four areas will be brought in to lead discussions on the topics. The opening speaker will be Derek Nepinak, Grand Chief of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs.

Kinew finished his talk on a positive note, emphasizing the need for First Nations in Canada to gain a global perspective, and to share the unique perspective that they have with the world.

“You don’t have to lose your indigenous identity in order to be a player in the global economy. You don’t have to lose your ties to your home community in order to participate in that form of modernity. These things can aid you in that and don’t have to hold you back.”