In light of a recent UNAIDS report indicating drops of up to 50 per cent in new HIV infections in some of the most severely affected parts of Africa, as well as broader contentions that the “global infection rates for AIDS peaked in the 1990s, and death rates are starting to fall,” some might be curious about how our own locality fits into the international milieu.

Are rates of new infections going down in Winnipeg and Manitoba? What about AIDS-related deaths? What about the well-documented stigma that accompanies this viral infiltration of the human T cell?

By the most recent accessible statistics, about 1,100 people are living with HIV/AIDS in Manitoba, with most cases concentrated in Winnipeg. Since 2009, rates of infection have remained fairly steady, or even dropped off slightly – 99 new infections were reported in 2009 and 102 in 2010, but only 80 new cases showed up in 2011.

Some might feel a particularly cautious brand of optimism beginning to swell as those last statistics are chewed over; the feeling is not entirely unwarranted.

One recalcitrant fact, however, stifles excitement. It is still true that in Manitoba, and in Canada, Aboriginal people are overrepresented in those new infection numbers. The 2011 Manitoba HIV Program Update, which contains the most up-to-date epidemiological information available to Manitobans, shows that 53 per cent of new cases from that year were from self-identified Aboriginal persons. Fifty-three is a startling jump from 38 per cent – the proportion of new Aboriginal patients seen in-province the previous year.

Attention should also be drawn to the fact that approximately 28 per cent of Canadians living with the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) do not know that they are infected – that is, 12,800 to 21,000 cases remain undiagnosed. In Manitoba, 16 per cent of known cases are classified as “critical late presenters” by the Manitoba HIV Program.

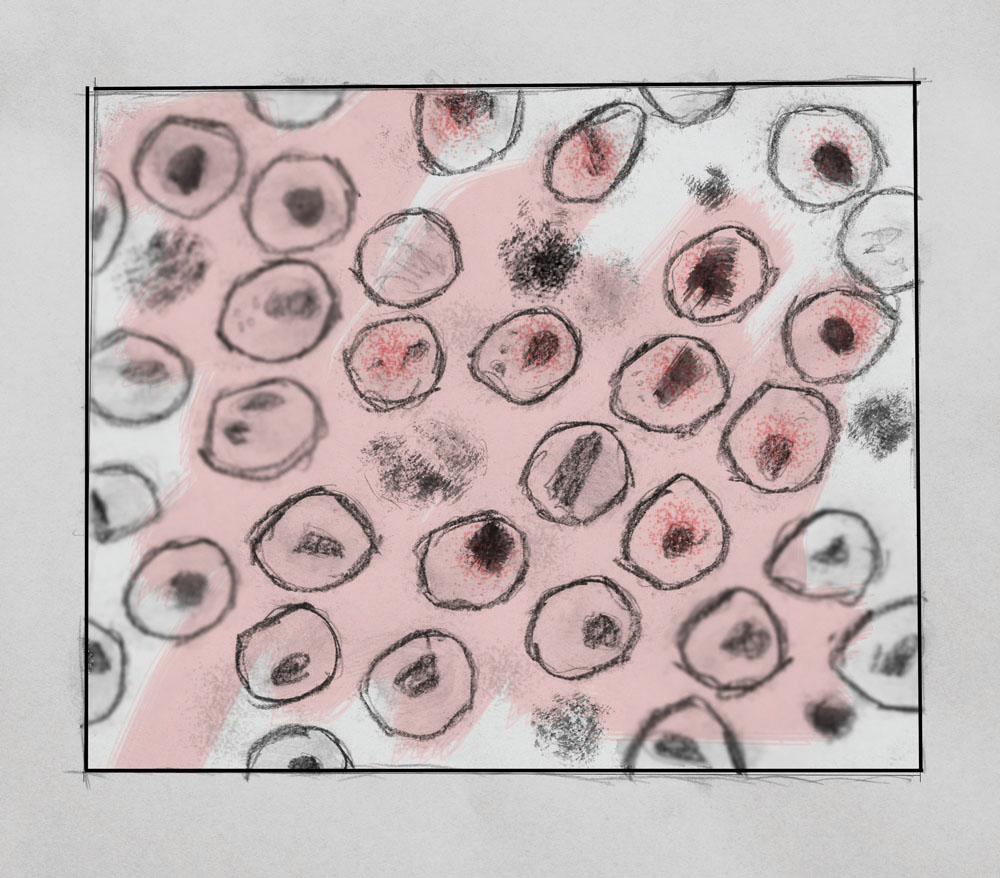

These cases are troubling for several reasons. One, they represent an increased viral load and decreased number of CD4 T cells (critical players of the cell-mediated immune system) in the individual. Two, late-presenting cases are costly to treat and account for 80 per cent of total provincial spending on HIV/AIDS treatment. Lastly, and perhaps most frustratingly, they could be avoided with increased testing.

“Testing rates are low across the country,” a representative of Winnipeg’s Nine Circles Community Health Centre told the Manitoban. “As a result many people are diagnosed late in their illness, which complicates treatment considerably.”

In Canada, unlike in Cuba in the late 1980s, the seropositive were never segregated and locked into a “national sanatorium,” but as Jacalyn Duffin notes in her book History of Medicine, this was “despite initial demands to the contrary.” And even today, here, in Winnipeg, Manitoba, and across Canada (the cradle of progressive politics), persons living with HIV/AIDS face a stigma.

“We are 30 years into the epidemic but HIV remains one of the most misunderstood illnesses in our communities. People living with [HIV] continue to face stigma and discrimination,” said a Nine Circles representative on condition of anonymity.

The battle against stigma will be won via public education. The Stigma Project, followed by a “dot org” on the world wide web, disseminates current information regarding HIV, implores readers to “live HIV neutral,” and recently released a series of posters demonstrating how inaccurate notions of HIV/AIDS are often embedded in the way we speak about the subject. In Winnipeg, Nine Circles is a hub for information on HIV/AIDS, as well as support and treatment.

Despite the availability of information, one important question is left without a definitive answer: What will it take for Manitoba to see a drop in new infections rates such as UNAIDS just reported for Eastern and Southern Africa?

The answer has something to do with recognizing that HIV/AIDS is a fluid concept. It manifests itself in subtly different ways in different places and times. The kind staff member at Nine Circles elucidated this concept for me.

“In Manitoba, the majority of people contract HIV through heterosexual contact, unlike Saskatchewan where the majority of new infections are amongst people who inject drugs. In Manitoba our response has been tailored to the unique elements of the epidemic in our province. Saskatchewan has done the same in their response,” the representative said.

A malleable solution to a malleable problem. Thankfully, this type of thinking is already commonplace.

Further, it must be taken to heart that treating HIV/AIDS consists of more than adding to the pharmacopoea.

Oliver Wendell Holmes supposedly said in 1883, “if the whole material medica as used, could be sunk in the bottom of the sea, it would be all the better for mankind and all the worse for the fishes.” To be completely honest, I could not disagree more. Modern pharmaceuticals are absolutely central to managing HIV. But I accept the implication that there is more to treating (and eradicating) an illness than drugs. There is more to well-being than seeing a good doctor.

For example, HIV needs to be managed at the population level. This is a politico-socio-economic disease. According to my correspondence with Nine Circles, the province of Manitoba recently cut funding for rapid HIV tests. This is the wrong move, especially if we agree that prevention is a big part of the cure. Needle exchange programs should become more advertised and widely available. Free condoms should be ubiquitous.

In closing, a quote from the experts at Nine Circles is most appropriate. Surely, it applies to our city as well:

“Getting to Zero is one of the UNAIDS goals. Internationally, a theme in worldwide AIDS response is ‘Getting to Zero: Zero new infections, zero AIDS-related deaths, and zero discrimination.’ It’s a high standard [ . . . ] It will take a long time to get there but every little step counts.”