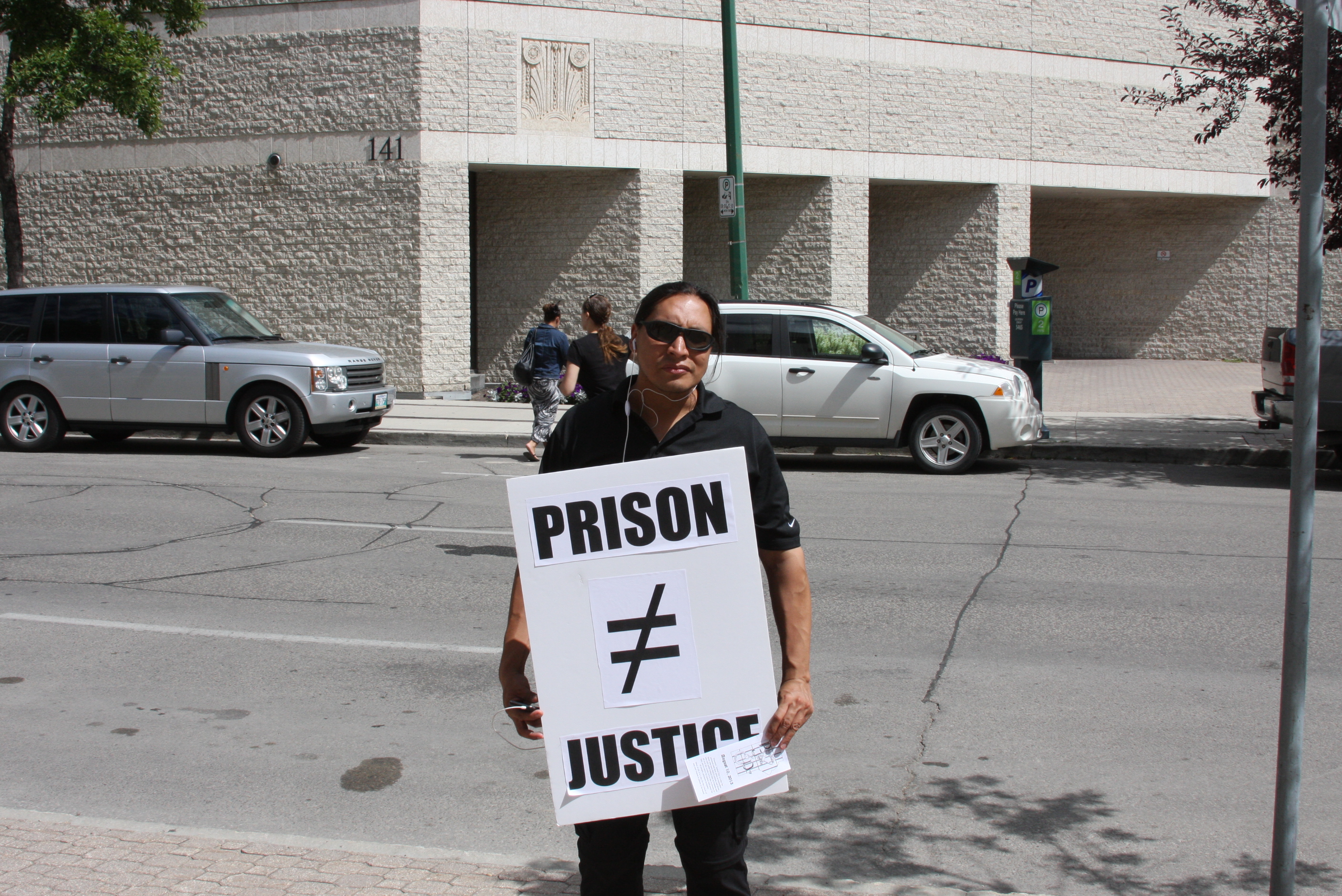

Wendell Smith stood on the Kennedy Street sidewalk between the Old Law Courts and the Winnipeg Remand Centre (WRC), equipped with a handmade sign reading “prison [does not equal] justice.” Smith said he was happy to be participating in his first Prisoner Justice Day (PJD) on the outside.

People gathered along with Smith on the sidewalk, listening to traditional Anishinaabe singing and drums, and waving to the one-way windows of the pre-trial detention centre. Prisoner Justice Day is held every Aug. 10, inside and outside of prisons across Canada, as “a day for prisoners and their allies to remember those who have died in prison, and those who still suffer behind bars in Canada and all over the world.”

While speakers share stories of their incarcerated loved ones who have lost their lives behind bars, prisoners commemorate the event by fasting and refusing to participate in work.

In Winnipeg, the Elizabeth Fry Society (EFS) organizes PJD events, in conjunction with the John Howard Society of Manitoba and a handful of other organizations to advocate for the rights of Canadian prisoners.

Tracy Booth, executive director of EFS, was involved with bringing PJD to Winnipeg five years ago. She spoke to the Manitoban about the logic behind taking a day to draw attention to the rights of incarcerated persons.

“I wanted to start something here to bring awareness to human rights, and the fact that when you are incarcerated, you should get the same physical care and access to mental health resources as you do when you are on the outside,” said Booth.

The stories shared on Kennedy Street during PJD indicate that that standard is not always met.

The family of Kinew James spoke about her death in Prince Albert prison this year. James, who was not in solitary confinement, reportedly pushed her call button repeatedly, as did other prisoners on her behalf, to no avail. The family says she was left for about an hour without being checked on, and when she was, she was found dead in her cell.

The family of Donald Ray Moose, who died in jail in 2009, also shared their story at the event. According to Louise Moose-Gotkin, Donald’s sister, he died from being overmedicated with the antidepressant amitriptyline, which was prescribed to him.

Moose-Gotkin told the Manitoban that an inquest was called into her brother’s death after finding that he had been overmedicated.

“For two years, we couldn’t get the proper autopsy report. I don’t know what they were trying to hide [ . . . ] when we did get the results of the autopsy, they called the inquest, which took another year,” said Moose-Gotkin.

The inquest started in April, but has since been delayed as the family looks for funds to pay their lawyer.

Tracy Booth said that prisoners often do not receive consistent quality health care in provincial institutions because their treatment is funded under the province’s justice budget rather than its health budget.

“In other provinces they do not silo their budgets, so if you have health care needs, that is billed under the department of health. One of the biggest issues in this province is that because there is such a high rate of incarceration, health care is not delivered because of how the budgeting occurs,” explained Booth.

She said that mistrust of medical staff by prisoners has not historically been a problem. “The issue is access,” Booth confirms.

Chickadee, a human rights activist who has been involved with PJD activities in the past and also previously worked within the walls of the WRC, spoke critically about the treatment of prisoners within that institution.

“I think it was an overexertion of power and authority. I saw some of the guys get beaten pretty badly, where they were put in segregation until their bruises and bumps healed,” said Chickadee, recalling her time working with WRC inmates. She also recounted experiences in which reasonable requests for medication were denied, and where babies were stillborn as a result of neglect.

Chickadee told the Manitoban that she filed many complaints in regards to these incidents, but no one ever got back to her.

Following speeches from the James and Moose families, as well as Booth, the crowd participated in a traditional song and then broke into a round dance. Prisoners on some floors could be faintly seen waiving the inside of chip bags in front of their windows.

Booth said this year had been the largest turnout, in comparison to the previous four years of PJD in Winnipeg,.

“Each year, I’ve wanted it to grow more, and this year the seed has finally grown. I wanted more organizations and community to be involved, so I am very happy.”

Elsewhere in Canada, PJD was recognized in a similar fashion. In Toronto, for example, a six-hour gathering was held in a church. The John Howard Society of Toronto and Elizabeth Fry Toronto sponsored the event.

Prisoner Justice Day began on Aug. 10, 1975, inside Bath, Ontario’s Millhaven Institution. Prisoners inside Millhaven refused to work or eat for 24 hours to commemorate the death of Eddie Nalon, a prisoner who died of a self-inflicted wound while in the institution’s segregation unit exactly one year prior.

In 1976, the Aug. 10 hunger strike spread to many prisons across Canada. According to the website of the Vancouver Prisoner Justice Day Committee, by 1983 Prisoner Justice Day spread to France, where inmates “refused to eat in recognition of August 10,” and had a statement of solidarity with prisoners worldwide read on their behalf on a Paris radio station.

Officials at WRC declined to comment to the Manitoban on the Winnipeg PJD events.

of course they were all innocent

The article does not allude to any sort of claims to innocence. The day of action is essentially advocating for basic human rights in institutions where people are wards of the state.

chi megwich for the wonderful article, Quinn Richert