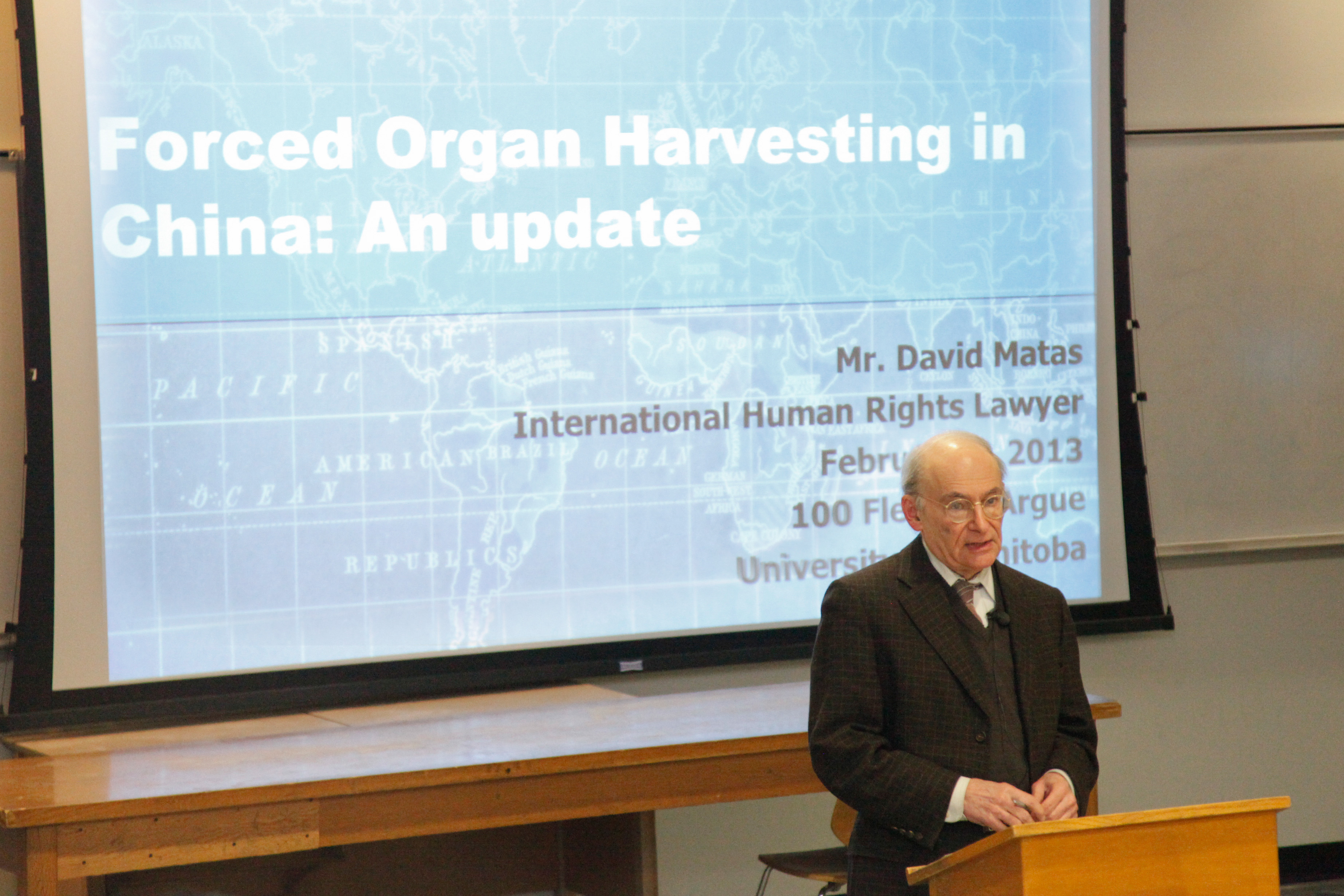

International human rights lawyer David Matas was at the University of Manitoba on Feb. 1 to talk about the issue of forced organ harvesting from incarcerated Falun Gong practitioners in China.

Matas’ talk was sponsored by the U of M’s Arthur V. Mauro Centre, the Centre for Human Rights Research, the faculty of social work, and the departments of sociology and Asian studies.

Falun Gong, also known as Falun Dafa, is a form of meditation and exercise, imbued with spiritual teachings, which has, in recent years, “become a subject of much communist propaganda in China,” according to Matas.

Matas explained that, as Falun Gong gained popularity in the mid-90s, the Chinese Communist Party moved to outlaw the practice.

“By 1999, Falun Gong were, according to a government survey, more numerous in memberships than the Communist Party. Out of fear of losing its ideological supremacy and popularity, the party banned Falun Gong.”

Doctors Against Forced Organ Harvesting spokesperson Dr. Damon Noto claims that by the end of that same year, “the number of transplants taking place just exploded.”

Many, including Noto and Matas, point out a disparity between the number of organ transplants performed yearly in China and the number of criminals executed by the state – China’s acknowledged source of most transplanted organs.

Two books published by Matas, entitled Bloody Harvest and State Organs, argue that the most likely source of unaccounted-for organs is from Falun Gong practitioners held in labour camps. These individuals, who are not formally sentenced to the death penalty, are routinely blood-typed and subjected to various medical tests while detained and then killed for their organs when required.

“There is no explanation for the transplant numbers in China other than sourcing from Falun Gong. China is the second largest transplant country in the world other than the U.S., yet, up until 2010, China did not have a deceased donation system and, even today, that system produces donations [that] are statistically insignificant,” Matas said to the U of M crowd.

The second half of Matas’ talk transitioned into a 12-point plan on how Canada’s government and citizens could pressure China into ending forced organ harvesting.

Matas thinks that Canada can enact extraterritorial legislation in order to cut down on “transplant tourism” to China.

“Parliament should enact legislation to combat international organ transplant abuse. A legislative initiative in this area would highlight the importance of any abuse and strengthen the position of those in China who are actually subjected to it,” said Matas.

Furthermore, Matas says Canadian academic institutions should “deny admission to Chinese medical professionals who are training in transplant surgical techniques, unless the would-be trainees commit to not engage directly or indirectly in the use of organs from prisons.”

Following his talk, Matas told the Manitoban that, while there is a cultural aversion toward organ donation in China, the Communist Party has the power to reverse such thinking – involuntary organ harvesting is much too lucrative.

“China has managed to overcome a lot of its historical cultural traditions [ . . . ] If the Chinese Communist Party put a priority on donation, there would be more than enough donations. If the party said, ‘in order to be a member of the party, you have to sign up with the donation program,’ it would happen overnight. The reason it hasn’t happened is not cultural aversion. There is just too much money being made from organs [ . . . ] there [are] a lot of vested interests that want to keep this system.”

Maria Cheung, a social work professor at the U of M and chair of the discussion, said that some of the discrimination faced by Falun Gong practitioners has carried into Canada, and has been noticed on the U of M campus.

Cheung says that many Chinese students think that Falun Gong practitioners run the independent Chinese newspaper, the Epoch Times, which can be found for free at the main entrance to University Centre.

“If you walk past the Epoch Times you can do a survey every week. Sometimes people flip it over or try to cover it with something. These are very subtle ‘micro-aggressions,’” said Cheung.

Cheung says she hopes that she can continue to work towards eradicating feelings of suspicion or hostility towards Falun Gong practitioners on campus.

On Jan. 29, the U of M’s Falun Dafa group showed the film Between Life and Death: Falun Gong Practitioners Systematically Murdered for Their Organs as part of the University of Manitoba Students’ Union (UMSU)’s International Movie Festival.