Prominent web programmer and open data activist Aaron Swartz was found dead in his apartment on Friday, Jan. 11 in an apparent suicide. He was 26. Swartz’s family released a statement criticizing the way he was treated by MIT and the U.S. justice system in the last few months of his life.

Swartz was accomplished at a young age. At 14, he already had the creation of an important web standard under his belt. RSS (Rich Site Summary) is a simple markup language that allows websites to send out notifications of updates in a format that is easy for computers to interpret and manipulate. Usually represented by white radio waves on an orange square, it is a widely used format, especially on blogs and news sites that update frequently. Swartz was a member of the working group that drew up the RSS 1.0 specification in 2000.

Swartz also founded several organizations and companies during his short life. One of these, known as Infogami, merged with the popular news site Reddit in late 2005, and Swartz became a co-owner of the parent company, Not A Bug.

While working at Reddit, he developed a new web framework in the Python programming language called web.py. This was later published and released into the public domain, and is now in wide use. The public domain licence, very unusual even for a free software project, was part of Swartz’s general open data ethos. He advocated vigorously for less restrictive licensing and greater availability of data – among other things, he founded DemandProgress.org in 2010 to campaign against the SOPA (Stop Online Piracy Act) and PIPA (Protect IP Act) bills in the U.S.

Swartz was plagued by chronic illness and depression. He had experienced suicidal thoughts at low points in the past.

“Everything you think about seems bleak,” he wrote in 2007, “the things you’ve done, the things you hope to do, the people around you. You want to lie in bed and keep the lights off. Depressed mood is like that, only it doesn’t come for any reason and it doesn’t go for any either.”

Swartz’s family and friends blamed his persecution on the Massachusetts U.S. Attorney’s office and the lack of support from MIT for contributing to his suicide.

Swartz’s open data activism had landed him in hot water in the past. In 2009 the FBI investigated him after he downloaded almost 20 million pages of text from PACER, the Public Access to Court Electronic Records system. PACER’s documents were all a matter of public record and free from copyright, but the electronic system was decades out of date and the only way to access the data was to pay eight cents a page for a printed copy.

With some court records running to thousands of pages, this could get very expensive. When a free trial of PACER was run in 17 libraries throughout the States, activist Carl Malamud urged people to retrieve as many documents as possible and send them to him to be republished online. Aaron Swartz read Malamud’s appeal and wrote a program to download an estimated 20 per cent of the PACER database.

The Government Printing Office shut down the free trial, claiming their security had been breached, and had the FBI investigate Swartz. He was investigated, but the incident petered out without charges being filed because he and Malamud had not done anything illegal.

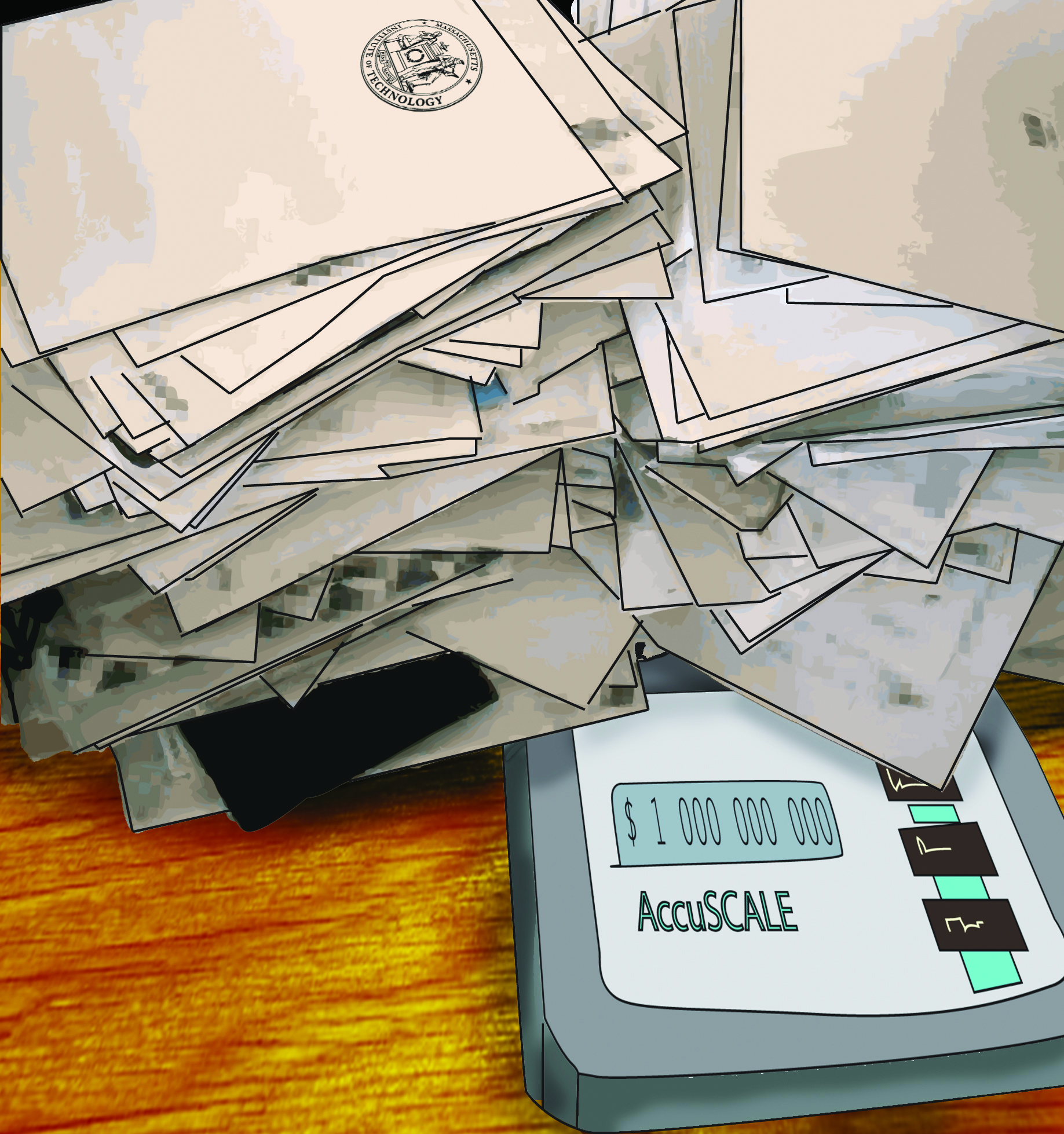

Most recently, though, Swartz got into trouble for allegedly downloading 4.8 million academic articles from the database JSTOR. For a subscription fee, JSTOR offers practically unlimited access to its large database of academic articles to large institutions. Allegedly, Swartz broke into a basement network closet at MIT (which had given him JSTOR access via a guest account) and hid a laptop there running a program to download JSTOR articles. This involved circumventing MIT security and breaking the JSTOR terms of service, but whether it is a crime has been considered a much thornier question. The CEO of DemandProgress.org likened it to “trying to put someone in jail for allegedly checking too many books out of the library.”

JSTOR was satisfied when Swartz returned all the documents and declined to pursue civil charges against him, but Carmen Ortiz, U.S. Attorney for the district of Massachusetts, took up the case. Swartz was indicted in July 2011 on 13 felony charges, with potential penalties of up to 35 years in prison and US $1 million in fines. He pleaded not guilty on Sept. 24, 2012, and the trial was set for next month.

After his death, Swartz’s family released a statement criticizing his treatment by the justice system.

“Decisions made by officials in the Massachusetts U.S. Attorney’s office and at MIT contributed to his death. The U.S. Attorney’s office pursued an exceptionally harsh array of charges, carrying potentially over 30 years in prison, to punish an alleged crime that had no victims. Meanwhile, unlike JSTOR, MIT refused to stand up for Aaron and its own community’s most cherished principles.”

They asked that donations be made in his memory to the charity organization GiveWell.