Are organic produce and animal products more “nutritious” than conventional counterparts?

In September of this year, a study entitled “Are Organic Foods Safer or Healthier Than Conventional Alternatives?” was released by a group of Stanford medical researchers. Crystal Smith-Spangle et al concluded, “The published literature lacks strong evidence that organic foods are significantly more nutritious than conventional foods.”

The study is what is known as a meta-analysis: the statistical technique of pooling data from independent studies in order to identify large-scale overarching trends in “the published literature.” One limitation to meta-analysis is that there is often high “heterogeneity” between the pooled studies. This means that while it is possible to track select variables of interest (i.e. nutrient content) across independents studies, one runs the risk of over-generalization, sacrificing detail in the name of finding a common trend amongst studies.

Smith-Spangle et al scanned archives and found nearly 6,000 relevant scholarly research articles. Around 240 of the studies “met inclusion criteria” – 223 of which concerned nutrient concentration differences between organic and conventional food products, while 17 focused on clinical health differences resulting from conventional and organics-based diets in populations.

One of the main and much publicized elements of the study, again, was the reported finding that the “comparative health outcomes, nutrition, and safety of organic and conventional foods identified limited evidence for the superiority of organic foods [italics added].”

The research was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine on Sept. 4, and was quickly picked up by various media outlets – including the local CBC Radio One. A weekday afternoon program featured host Larry Updike interviewing University of Manitoba professor, Rick Holley, about the study’s findings. Despite admitting to the positive environmental impacts of organic versus conventional farming and food production systems, Holley sounded otherwise unsurprised by the finding that nutritional content differences were negligible between the two options.

Regarding organic products being healthier than conventional products, in an interview with the Manitoban Holley remarked, “There are no legal claims that can be made with regard to that effect that I am aware of. In fact, I’m pretty certain it would be illegal to make a health claim based on nutritional content of an organic product versus a conventional product.”

Holley has a background in both industrial and government research, though he’s been in the U of M’s Food Sciences department for the last 18 years, looking at the impact of animal management systems on food-borne illness and the spread of bacteria to food.

According to Holley’s experience and familiarity with research in the organic/conventional foods debate, the case has already been established elsewhere, and this study is “confirmatory work” more then anything.

Holley went on to explain that other studies have had similar outcomes with respect to the measurable nutrient differences between organic and conventional foods, with the “balances going towards organics.” But, in Holley’s words, that’s been explained by the fact that “organic produce grows more slowly than conventionally raised produce.

“What happens is you have products grown organically that seem to contain a little less water and so the nutrient content [appears] a little higher per unit of vegetable or fruit.”

Organics less “contaminated?”

“It’s the media that really made health claims about organics in the first place,” stated U of M Plant Sciences professor, Martin Entz, in an interview with the Manitoban.

“The organic movement really started as an environmental movement, as a political movement, and as a social justice movement. It really didn’t start out as a food quality movement. So the media is kind of having a discussion with itself there.”

Entz has been studying organic agriculture around the world for over 20 years and is part of the U of M’s Natural Systems Agriculture project conducted at the Glenlea Research Station, located 20 kms south of the U of M’s Fort Garry campus.

Perhaps one of the lesser-publicized details of the study was the finding that organic produce had less exposure to antibiotic-resistant bacteria and pesticide residues. Organic produce was on average 30 per cent less likely to contain detectable amounts of contaminants (pesticide residues) than its conventional counterpart. In addition, conventional pork and chicken products carried a 33 per cent greater risk of containing bacteria resistant to “three or more antibiotics” than did the same organic products.

Though these organic food products did not hit the magic “zero tolerance” levels many would hope to see, they still contained lower levels of pesticide residue on average. However, from a toxicology perspective, the researchers added that the effect of detectable contamination levels found between organic and conventional food-consuming populations was “unclear because the difference in risk for contamination exceeding maximum allowed limits may be small.”

According to professor Holley, when toxicologists establish the maximum residue levels they are “based on lower levels of tolerance that are established in terms of weight of component per unit weight of an individual: [that’s] micrograms per kilogram of bodyweight, each day for the entire life of the individual.”

“The USDA has done work in this area as well to establish what baseline levels of [pesticide and antibiotic] residues might be in food products,” Holley continued.

Are organics ever “less” healthy?

“Having these meta-analyses are helpful in some ways. In other ways they do gloss over [important details],” maintained Entz.

Entz took issue with the study’s conclusion, describing it as a little naïve [ . . . ] given the parameters looked at.” Entz noted that researchers mainly measured nutrient content, but that there are other nutritional elements in food that may have been overlooked.

Offering as an example the levels of secondary plant metabolites present in produce, Entz reflected, “what we’ve learned in reductionist science is that a little stress is very good for plants; it actually increases their antioxidants because they’re increasing [the activity] of self defense mechanisms.”

The “stress” Entz mentioned results from the lack of pesticides present in organic farming. According to Entz, these increased stress levels lead to “increases [in the plants’] phenolic compounds, which are healthy for us.”

“Organic crops, because they’ve been subjected to more [environmental] stress, are actually higher in these beneficial secondary plant metabolites.” Entz added, “that is also part of ‘nutrition,’ and that is something they didn’t measure.”

Entz concluded, “Is organic food any less healthy? Never. Is organic food ever in some way better? Often.”

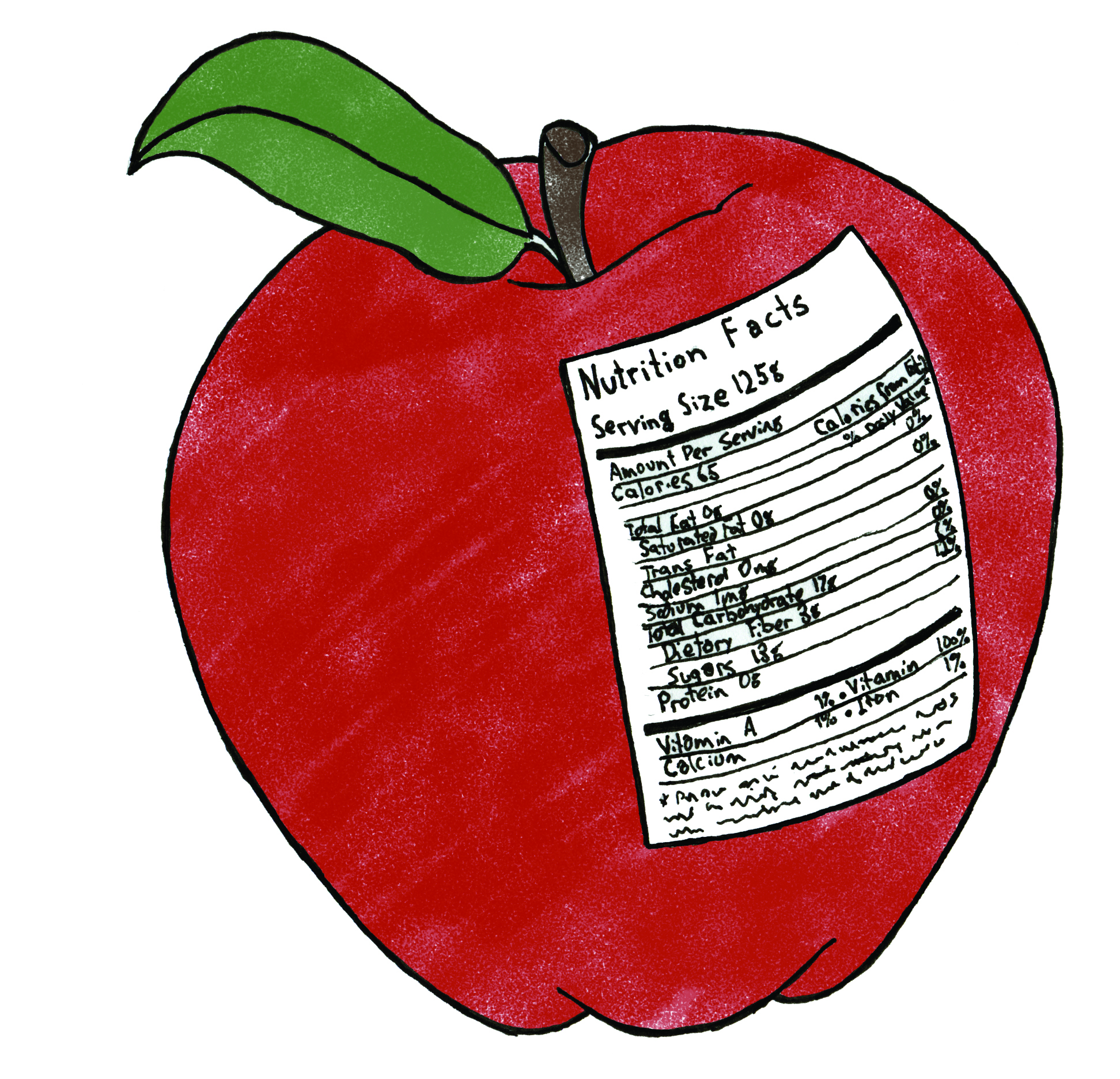

ILLUSTRATION AT TOP: Silvana Moran

ILLUSTRATION IN TEXT: Caroline Norman

My book on “Organic vs. Conventional Food: What Science Tells Us” (see http://www.field2foods.com) puts the agricultural perspective in these food types debate. Both organic and conventional foods (plant food) are the output of the same method of vegetable culture, i.e., cultivation methods encompassing site/land preparation, maintenance, and harvesting. Maintenance involves 1) Supplementing of the growth inputs of water and essential minerals that are in short supply; 2) Supplementing of protection inputs through physical, biological, and chemical control (booth organic and conventional farming use all three tactics); and 3) cultural practices based on the crop.

So everything is equal for both farming systems- organic fertilizer is the same as inorganic fertilizer chemically to the plant in terms of the principle of nutrition. A pesticide is a pesticide in any way or form by virtue that all pesticides contain an active ingredient that serves as the economic poison.

Why should the nutritional content/value be different? Have we forgotten that food (organic or conventional) is produced by natural processes [germination + nutrient uptake + photosynthesis + assimilation] biosynthesis? .. and NOT by a cultivation method?

Have we forgotten that nutrient as a characteristic of a plant food just as color, texture, pulp, seediness, etc. is determined by the genetic make-up of the plant? If we do remember that! then the nutrient content of a plant species/variety is FIXED based on the plant genome. To change nutrient content (in farming) the genes of the plant MUST be altered. How? It can happen naturally by mutation or influenced naturally by uncontrolled cross-pollination by insects, birds, wind and other nature intervention; it can also happen by human intervention by controlled cross-pollination or by genetic engineering. Of these four ways of gene alteration, GE is the only method that can specifically change the nutrient content of a food directly.

My book echoed the findings of the Stanford University, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (2009 study) and the more recent findings of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

Please find out more about five major food contaminants that can be detrimental to food consumers featured in my book.

Osmond Baron