If you want to go to law school in Canada, your grade point average and résumé are only the beginning. Standing between you and an admissions offer is a multiple-choice exam run by an American non-profit organization, the Law School Admission Council (LSAC).

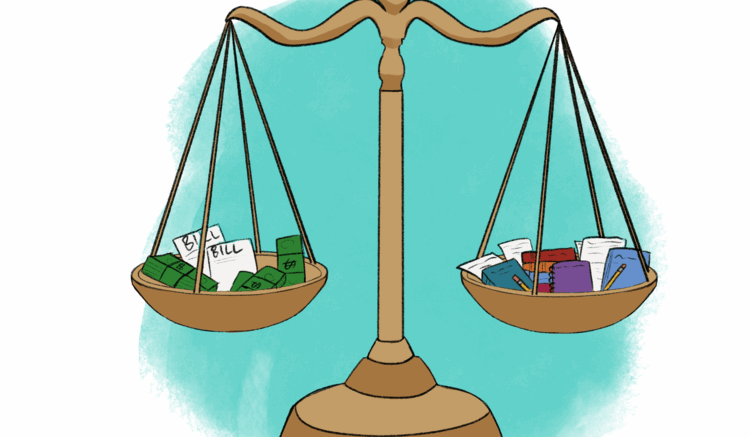

The Law School Admission Test, or LSAT, is a standardized exam scored from 120 to 180 that most Canadian schools still treat as a major gatekeeper. Officially, it measures logical reasoning and reading comprehension. Unofficially, in an age of widening income inequality, it also measures who has the time, money and stability to bend their life around an exam.

Start with the price tag. LSAC lists the LSAT fee in U.S. currency — currently $248 USD. By the time the exchange rate and taxes are added, many of us in Canada see a charge in the high three hundreds. That number does not include other costs such as prep books, online subscriptions, practice tests and, if you’re lucky, LSAT tutoring. Even if you rely on free resources, you still need a decent laptop, reliable internet and a quiet space — none of which are guaranteed if you are living with roommates, family or in unstable housing.

Then there is the cost that does not show up on a receipt — time. To be “LSAT-competitive,” applicants are encouraged to study for hundreds of hours. For some, that may mean rearranging schedules and cutting back on social life. For others, especially those working or caregiving, those hours can only be carved out of sleep or earning income. Studying for the LSAT may start to look like an unpaid full-time job.

At the same time, law schools tell applicants they are looking for volunteer work, leadership roles, extracurriculars and a thoughtful personal statement. In practice, that means a lot of people are trying to hold down paid work, manage family responsibilities, find time to volunteer and still produce a competitive LSAT score.

On the flip side, a system like this favours applicants who can afford to take fewer shifts, who have help paying rent, who can pay for a tutor when their practice scores plateau or who have family who have already navigated the process. When so much weight is put on the LSAT, it is not just logic being tested — it’s who can buy themselves time. It is worth asking what, exactly, this test adds to the process that everything else does not already demand.

I am not arguing that law schools should admit students without academic standards. The ability to read dense material, reason carefully and manage stress all matter in the practice of law. But the LSAT is a very particular way of measuring those skills, under very particular conditions. Even LSAC has acknowledged that the test is not untouchable. After a legal settlement with blind test takers, LSAC removed the logic games section because its reliance on drawing diagrams made it less accessible for many disabled students.

If an entire section of the LSAT can change in the name of fairness, it is hard to pretend that the test as a whole is some neutral, immovable standard. It is a timed, high-stakes, one-size-fits-all exam that does not account for whether someone has navigated poverty, eviction, immigration or the criminal legal system from the other side of the table. Those experiences, which are invaluable in a lawyer, do not appear as a higher score.

If anyone from an admissions committee at a school I have applied to happens to be reading this, consider it my very nerdy way of saying I am excited about the possibility of learning all that law school has to offer. I am just less convinced that one very expensive standardized test should have so much power over who gets to attend.

Right now, in a country where the cost of living keeps climbing, having the LSAT included and weighed heavily in admissions functions as yet another barrier that falls hardest on people from less privileged backgrounds. The law should not belong primarily to those who can afford the time and money it takes to master logic questions.