Mario Tenuta is a professor of soil science in the U of M’s faculty of agricultural and food sciences and senior industrial research chair in 4R nutrient management.

“It was very clear when I went to university that I really liked soils and plants,” he said. “So, I worked and studied, majoring in physical geography and botany.”

Tenuta pursued his undergraduate degree at the University of Toronto. He discovered his passion for soil science while working part-time with a professor to develop an instrument for measuring total nitrogen and carbon in soil and plants.

During his final summer, he conducted field research in Churchill, Manitoba, studying nitrogen cycling in remote soils along the Hudson Bay coast.

This inspired him to pursue a master’s degree in soil science at the University of Guelph, focusing on nitrogen transformations by bacteria, combining fieldwork, laboratory research and connecting to environmental and agricultural practices.

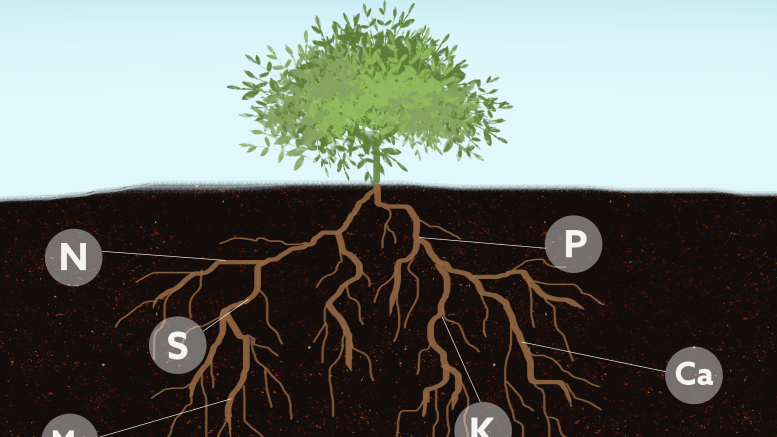

“We do several lines of research in my laboratory here at the U of M. The largest one, by far, is investigating nitrogen management, in particular nitrogen fertilizing management for the production of crops in agriculture,” he said. “We are examining fertilizers, and particularly nitrogen, for a number of reasons.”

Tenuta explained that farmers widely use nitrogen fertilizers because crops such as wheat, barley, canola and corn require substantial amounts of nitrogen for growth. This is crucial for food production, both to meet local demands and to export to other countries.

Nitrogen fertilizers are expensive for farmers, leading Tenuta to research improving their efficiency to help reduce costs for farmers.

Furthermore, the use of nitrogen fertilizers has considerable environmental consequences. They contribute to climate change by releasing nitrous oxide and can contaminate drinking water with nitrate. Consequently, managing nitrogen in agricultural soils is a critical area of focus.

“What we’re doing with the research chair and for nutrient management is looking at practices that farmers can use to improve the efficiency of their nitrogen use to produce crops and then also to reduce losses, particularly losses of nitrogen to nitrous oxide, and that’s our greenhouse gas,” Tenuta said. “Our research is showing different directions and/or practices that farmers can use to reduce losses.”

Tenuta stressed the importance of reducing nitrous oxide emissions caused by increased nitrogen fertilizer use, which results from the demand for high-yield crops. His research promotes sustainable farming practices to limit these emissions and lessen their impact on global warming.

“We have been researching additives to fertilizers that slow down the work of bacteria on the fertilizer,” he said. “It reduces the amount of nitrous oxide that is emitted or leaked away from the soil to the atmosphere.”

Tenuta is studying fertilizer application methods and nitrogen fertilizer products to help farmers make better decisions. By placing fertilizer deeper in the soil, losses of nitrous oxide can be reduced.

His recent research examines whether advertised nitrogen products truly improve crop yields and reduce emissions. This work aids farmers in choosing effective and cost-efficient solutions and contributes to environmental sustainability.

“We’re contributing to the economy and food production and helping farmers, but also consumers that eat the food,” Tenuta said. “We’re also affecting change for the better in the environment by reducing losses.”

“Our hope is that by demonstrating through really good science, and going outside to farm fields, studying how we can improve fertilizer use, in time, more and more farmers will adopt the practices.”

Tenuta emphasized the importance of adopting better practices to drive meaningful change, such as reducing nitrous oxide emissions. He highlighted that timely action is crucial and suggested strategies like using nitrification inhibitors and optimizing nitrogen application to help farmers significantly cut emissions.

“Canada has a target of reducing emissions of nitrous oxide by 30 per cent by the year 2030, but the only way we’re going to achieve that is by [providing] good information to farmers,” he explained. “Our work with our graduate students and their programs, the studies they do, and our undergraduates that help us out in the summer in the field with helping the graduate students, really demonstrate to farmers what can be done and how it can be done.”

“I’d really love if our students at the U of M appreciate or understand that there are options available to continue with studies and move more toward research and do masters and PhDs,” Tenuta said.