In 2017, I attended Tanya Talaga’s talk at the Millennium Library where she was promoting her book, Seven Fallen Feathers. Part of Talaga’s book is a damning account of the ways police racism and apathy toward Indigenous people and their well-being create more room for anti-Indigenous violence.

The book documents seven cases of Indigenous teens going missing in Thunder Bay, Ont., only for five of their bodies to be found in rivers. The teenagers were several kilometres away from their homes, all but one attending the same high school. All seven deaths were marked by law enforcement as accidents.

The rest of Canada is laden with the same problems Talaga documented in Thunder Bay.

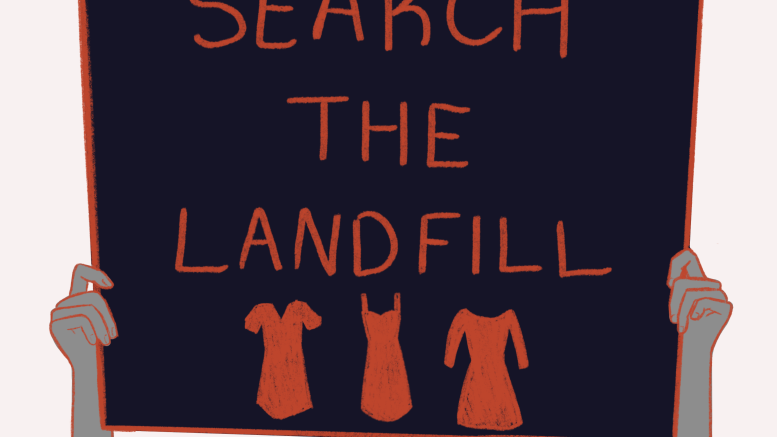

In Winnipeg, protestors have been camping since December 2022, when the Winnipeg Police Service (WPS) announced that the remains of two murdered Indigenous women, Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran, had likely been dumped in Prairie Green Landfill in the May of that year.

The announcement followed the discovery of the remains of Rebecca Contois, another Indigenous woman, in a dumpster. Like Myran, Harris and another unidentified woman currently referred to as Buffalo Woman, Contois is suspected to have been the victim of one serial killer.

Calls to search the landfill have not gone unanswered, but the answers protestors have received leave much to be desired. According to a statement from Manitoba Premier Heather Stefanson, the landfill cannot be searched because the potential safety risks are too great.

Safety as a vague concept should certainly be a concern, but what exactly would jeopardize the safety of search teams here? In this case, they might be exposed to toxic gases and asbestos deposits in the landfill. Of course, that isn’t the watertight argument it might seem to be at first blush. Experts remove asbestos from indoor areas regularly for far less than a missing person’s remains.

Not only that, but other landfills in Canada have been searched safely and successfully. The partial remains of Wesley Hallam were recovered in Sault Ste. Marie, Ont. after police searched three separate dumps around the town and another dump in Michigan.

Even WPS has conducted a landfill search without compromising the safety of its teams. Talaga has pointed out that WPS’s 2012 search of the Brady Road Landfill for Tanya Nepinak — who disappeared in September 2011 — was conducted safely.

Although WPS has not been clamouring to conduct the search despite the province’s reluctance. WPS claimed in December 2022 that searching the landfill was not feasible due to the amount of material deposited at the site and concerns that they would not be able to distinguish the remains from those belonging to animals.

At the time of its December announcement, WPS stated it determined in June that the women’s remains had likely been discarded in the landfill sometime in May 2022, and had concluded that a search was not feasible despite only one month having passed.

Even now, many months later, the window of feasibility has not been shuttered. Although there are concerns from researchers about starting a search after 60 days, research also points to layers of soil or spray-material covering garbage making the decomposition of the remains less likely.

One reactionary commentator parroted that 60 day figure, arguing that because that window has lapsed there is no longer any point in trying.

While it’s true that the best time to search the landfill was within the first 30 days of Harris’s and Myran’s bodies being left there, the prospect of success is not bleak enough to write off a search.

Then again, WPS has had its hands tied lately. WPS stated in a press release that major crimes would be investigating a case of productive vandals who sprayed more than 65 phrases like “ACAB,” “search the landfills” and profanities along the route for the World Police & Fire Games half marathon.

In Canada, vandalism is classified as mischief or the wilful destruction of property. If a case of mischief results in more than $5,000 in property damages, one may be imprisoned for up to 10 years. I do not think that spray paint on sidewalks and porta-potties ought to land someone 10 years’ worth of prison time.

Whatever the police are doing comes up repeatedly in this discussion because multiple levels of government seem content to wash their hands of primary, secondary or tertiary responsibility for funding the landfill search. The federal government provided $500,000 to the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs to conduct feasibility study, which determined that a landfill search was feasible. But the feds have made no commitment to funding the actual search.

Public officials seem to have committed strictly to shuffling their feet awkwardly and avoiding eye contact when pressed in the hopes that everyone just forgets about the whole thing. Stefanson said in her statement that while the four women who were murdered “will never be forgotten” and she had “met with the families,” she has “other responsibilities.”

So it seems that, for Stefanson, while these murdered Indigenous women will never be forgotten, it’s time to forget about them.

Not even busy public officials get to opt out. What ought not be left unsaid right now is that doing nothing— this is really doing something. If there is no plan to search the landfill, then our leadership is planning to leave human remains to rot in a pile of garbage.

The provincial government’s inaction sends a message that Indigenous people do not matter.

During the question period after Talaga’s talk in 2017, one member of the audience asked if there was a way to make people care about ongoing violence against Indigenous people. At the very least, I don’t think most settlers will care until leadership does.

Morgan Harris and Marcedes Myran need to be afforded the dignity of a final disposition, and all levels of government in Canada need to do the bare minimum and stop actively and aggressively failing Indigenous people through inaction.