Gabrielle Roy wrote about her departure from her childhood home in Manitoba with a sheepishness characteristic of anyone caught in this province’s nostalgic grip. No matter how much time lapses, this place stakes an eternal claim on anyone who loves it well.

Leaving can be hard, due to a sticky sense of obligation we have toward our childhood homes. Roy explored this delicately, writing, “we can’t return with impunity to the places that knew us when we were young,” even if we only left with the “innocent hope” of making something of ourselves.

Roy was born in St. Boniface in 1909 and spent some time roving around Manitoba in different teaching appointments. From her late 20s onward, Roy spent most of her time in between Europe and Quebec before passing away in Quebec City in 1983.

A sensitive, sympathetic and attentive writer, Roy is one of the defining voices of French-Canadian literature of the 20th century with a perspective that endures. Even with this July marking the 40th anniversary of her passing, her work bottles the hum-drum and charm of everyday life in a way that is still agonizingly relatable decades later.

Originally published in 1945, Roy’s first novel — translated into English as The Tin Flute — is told from the perspectives of a handful of navel-gazing wanderers. As preoccupied as they are with their love lives or the possibility of a better future away from Saint-Henri, Que., they stroll through Montreal absorbing every detail of the city. The end result is an illustration of a society in sharp definition, cold and awash with its residents’ yearning.

Well before the novel was translated to English from its original French, The Tin Flute was an instant success partly for anthropological reasons, spotlighting the very real social and economic struggles of the people in Saint-Henri.

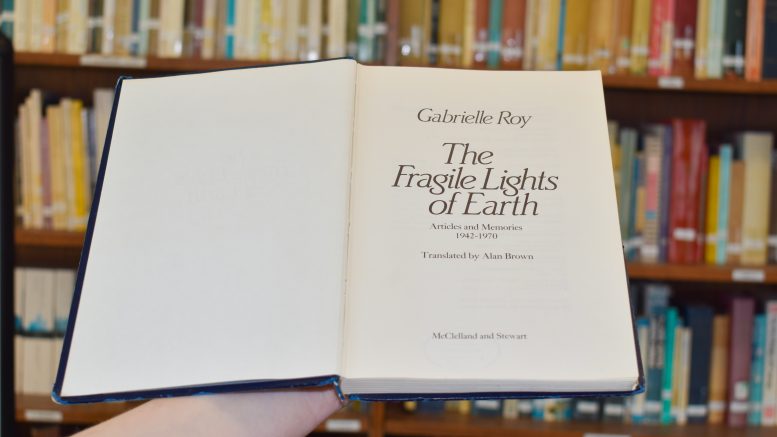

This thoughtful, observational point of view is on-brand for the author. Roy’s collection of non-fiction writing, titled The Fragile Lights of Earth: Articles and Memories 1942-1970, offers a glimpse into the mind of a perceptive sweetheart with a sour streak.

There are little comments about how Portage and Main feel like “the windiest streets in the world,” which are endearing and relatable. Sentences later, though, Roy will write with ruthless honesty.

To her, “even Winnipeg presents a strange, disconnected aspect with its miserable little shops hemmed in between modern buildings, and here and there an old wooden house of 1900 vintage.” She goes in for the kill, writing that “Winnipeg must appear to be no longer a pioneer town, but a city in the midst of transition.”

It is a little freaky and a little sad how relatable Roy’s descriptions of Winnipeg are in 2023 despite this year marking Fragile Lights’ 45th anniversary, as well as the fact that some of its contents were published decades earlier. The city’s identity came solely from its potential even back then.

A diverse population was part of prairie life for Roy, and it was ultimately something she celebrated. She wrote that visiting Winnipeg had its own benefits, as “without having to travel, [she] could see the peoples of the earth parade before [her] eyes.”

There are exceptions to this general love for the diversity of Treaty 1’s peoples. Roy describes Louis Riel as a “prophet to some, a traitor to others, a visionary, man of passion, vehement and perhaps, at certain times in his life, victim of a kind of delirium.”

Naive and laden with the settler-Canadian biases that hide themselves under the guise of disengagement, Roy’s commentary on Riel falls flat here because she just will not explain how she feels about him. She withdraws her signature attentiveness from her recollection and ultimately comes across as perplexed and tone-deaf.

Obtuse takes on Indigenous history are to be expected from settler authors, but Roy’s general mindfulness makes these moments where she trips all the more obvious.

She wrote once that she “would rather leave Manitoba on the note of a summer impression — the excessive summer of those parts, which we always loved so much.” That was the impression she left the world on, too, in high summer.

Roy’s memories of Manitoba preserve a piece of prairie life and show that in many ways, very little about this place has changed, including the good and the bad.

My loved ones have communicated something close to a feeling of betrayal when I have talked about how my life might carry me away from Manitoba. I think there is a sense here that we must be loyal residents of our province because it has been loyal to us. But, as Roy wrote, your home is “the place to which you go back to listen to the wind you heard in your childhood.”

When I think back to what always took my breath away, it was the weight of Winnipeg’s wind when it walloped me with humid, high summer heat.

Despite living the better part of her life away from Manitoba, Roy’s childhood home in St. Boniface stands to this day as a house museum — La Maison Gabrielle Roy — preserving a piece of her early life for visitors to analyze in their own time, just like her memorable stories.

Gabrielle Roy’s work is available through the University of Manitoba libraries.